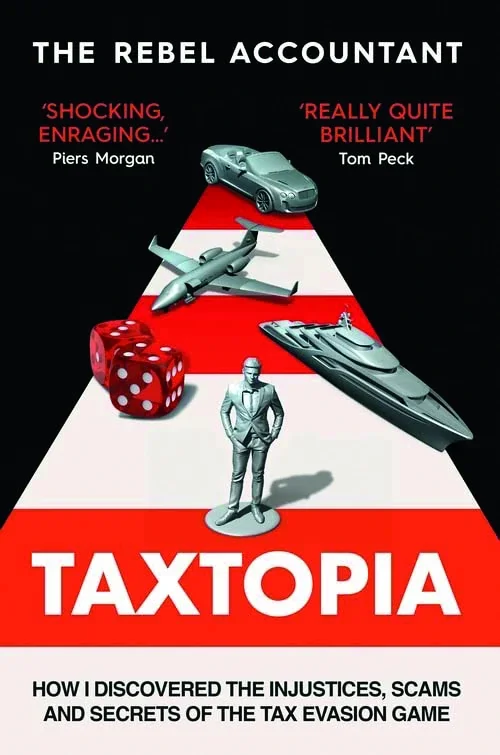

‘Everyone needs to read a book about tax, but no one wants to’ is the bold pitch that opens Taxtopia. It sounds rather daunting – discouraging, even. But sometimes a policy of radical transparency really is best.

Up to a point, however. Because the author of the book has chosen to remain anonymous. Or, in fact, pseudonymous. We are already familiar with the Secret Footballer, the Secret Barrister, the Secret Teacher and a variety of other noms de plume, but now we can add the Rebel Accountant to the list of authors in the slightly crowded genre of what you might call ‘professional confessional’.

The tax system is rigged

At least the underlying thesis of the book is straightforward, if sometimes a little conspiratorially phrased: the tax system is rigged. Deep within the byzantine reaches of the fortress of paperwork and bureaucracy erected against anyone seeking to understand UK taxation – 32,000 pages of legislation, not including the various bits of case law, guidance, treaties and other works necessary to see the system as a whole – lies a single, glowing gem of truth: it’s rather better to be rich than poor.

The tax code is rigged to favour the wealthy and powerful, who write the rules (or at least have a good deal of sway over those who do). The law is so riddled with loopholes and exceptions, so overly complex, that at the margins a system of law which is workable enough for the majority of people gives way to a morass of ambiguity in which how much certain people end up paying is a function of their appetite for legal risk and willingness to incur court fees facing down HMRC.

Not exactly a revelation?

To which readers of this magazine may respond: tell me something I don’t know. And, admittedly, I feel a similar way: my family ties to the Isle of Man, renowned as a tax h… – sorry, let me just double-check my wording here… renowned as a nimble, light-touch, tax-efficient regime – mean that reading how the tax sausage gets made is not exactly a shock.

But I also suspect that the kind of general readers who could be persuaded to pick up this book are aware that such wheezes as trusts, offshore companies and non-dom status can be used to avoid part of one’s tax bill, and that income taxation isn’t just limited to income tax.

What about fairness?

What’s more interesting is whether this is necessarily A Bad Thing. Broadly, I think most people would agree with the author that people in the same circumstances should pay pretty much the same rate of tax. This idea of fairness gives legitimacy to the taxes we pay.

However – and the author does take pains to point this out – not all people are in the same circumstances, and those who are very wealthy often have quite a lot of options for moving their money around offshore. In this context, arrangements which bring some money into a country are better than the alternative sort of capital flight experienced by France after the introduction of its wealth tax.

Economically speaking, the goal of a tax system is to fund the necessary activities of the state while minimising the level of distortion created. In some circumstances, this does mean lower taxes on the wealthy than the poor, or on wealth than income. But these arguments are at an almost complete tangent to the book, which doesn’t really engage with them at length.

Absurdly labyrinthine

Instead, it does a very good job of highlighting just how absurdly complex the current system is. From tax breaks for film producers to the correct imputed prices for imported goods to the various arrangements used by global companies to shift profits around jurisdictions, an admirably broad range of tax concepts are covered in a reasonably light and entertaining style.

The framing device used for these concepts is the arc of the author’s career, from entering the profession as a trainee accountant, then working their way up to relatively senior status at a firm catering to the very rich.

These parts are often quite funny, but as nobody would buy the autobiography of an anonymous accountant, they primarily serve to structure each chapter’s observations on a particular area of tax law. Because that might cause readers to wince and put down the book once the going gets too technical, each is studded with bits of history (why does England have such a curious tax year?) and particularly prominent cases.

Feeling the moral burnout

Throughout the arguments, the author also recounts their growing moral dissatisfaction with what they found themself doing. Was it actually reasonable to assist people in lowering their tax burden?

Sure, there’s always Lord Tomlin’s observation that ‘every man is entitled, if he can, to order his affairs so that the tax attaching under the appropriate Acts is less than it otherwise would be… however unappreciative the Commissioners of the Inland Revenue or his fellow tax-payers may be of his ingenuity’. But that’s a statement of law, not of morality.

It’s an interesting arc. Other professional authors, who will remain nameless, often seem more interested in defending what their industry does and explaining why any perceived flaws are actually good, or the fault of government officials.

That is emphatically not the tack taken here. The government gets plenty of stick for creating loopholes that are abusable, and for enabling bad behaviour – but accountancy gets just as much for having the sort of questionable ethical standards we more usually associate with disreputable sorts like used car salesmen, members of parliament and, yes, journalists.

Time to simplify the tax system?

The book concludes with the author’s answer to an interesting question: is it better to have a complicated tax system or a simple one? Perhaps unsurprisingly, the author comes down very heavily on the second side, and sets out their preferred array of tax reforms in the final chapter. For various policy reasons, I wouldn’t implement them as laid out, but the thrust is interesting.

In turn, this review finishes with another question: would I recommend the book? For readers of Spear’s, my answer is ‘yes, and it may also be worth going back over some of the more interesting ideas with your accountant’. For general readers, the answer is divided into two groups. If you are interested in policy, then you may well enjoy this.

If you are not, then I suspect that you will find your eyes glazing over in places, as your mind drifts off and you find yourself absent-mindedly wondering whether it’s still possible to take to the high seas, set course for Tortuga and join an economy where the closest thing to taxation is issuing shares to the crew after pillaging the Spanish Main. For these readers, there’s always Master and Commander.

Top image / Hachette

Order your copy of The Spear’s 500 2023 here.

More from Spear’s:

Book review: The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism