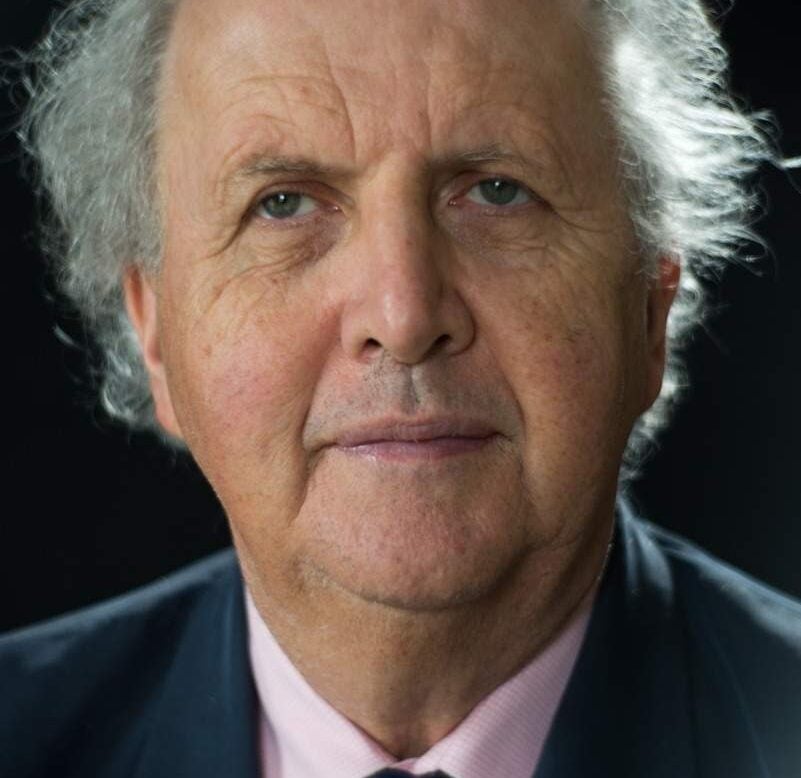

The novelist Alexander McCall Smith describes his global travels and finds joy everywhere from the US to Jaipur

It has been a very good year for mackerel. Nobody knows quite why this should be, but the shoals of these fish that move up the west coast of Scotland in the summer months have been particularly plentiful. We have a house on that coast, tucked away on the shores of a quiet sea loch – the term we use in Scotland for an inlet or fjord. All I have to do to catch mackerel is go out on my boat, within sight of the house, drop a fishing line with a half-dozen feathered hooks on it, and wait for the mackerel to accept the invitation. When I have enough, I row back to the shore and help with the filleting. My wife then smokes some in a domestic smoker and freezes the rest. Now, with enough to last us the winter, we had some for dinner the other night in Edinburgh. They are every bit as delicious as salmon or sea trout. For the most part, we have lost the connection between our food and how it is obtained. There is nothing like eating a fish you caught to remind you of these realities.

Caesar Days

I have just returned to Scotland from an American tour for my new book in the No 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency series. American tours are hard work: a different city every day, an early start to catch the next plane, and any number of Caesar salads, courtesy of room service. Being on a low-carb diet, as I am, means just about everything on the regular menu is off limits. Except Caesar salad sans croutons. In spite of such a routine, being in the Midwest, as I was for much of the tour, remains a pleasant experience. Why? The people. I find that people there are open and courteous in a way which becoming rather less common elsewhere. Young men address you as ‘sir’, people smile quite a lot, and there is a general sense of willingness to do things. It’s the same in Australia, where I find that the default position is friendliness. In Scotland, I fear, we can be a touch on the dour side. That is not to say that Scotland is unfriendly – it’s not that at all. It’s just that we tend to see the dark side. We shake our heads if the weather is good and say: ‘We’ll pay for it later.’ And unfortunately we do. We do have to pay for things later – not that that particular message is fully understood, I suspect, by all of our politicians when making their public spending promises to an enthusiastic electorate. However, let’s not get involved in national stereotypes, lest we say things like ‘the French enjoy a good riot’.

Picture by Alex Hewitt/Writer Pictures

World Rights

Feast of Festivals

Much of my time is spent attending literary festivals. These are wonderful occasions, and they are mushrooming up everywhere these days. Some of these take place in glittery places – I was at the Emirates Literary Festival in Dubai earlier in the year – while others occur in small villages or even in country houses: Charles Spencer holds a highly regarded literary festival in Althorp each year. The biggest literary show on earth, though, takes place in India every January. The Jaipur Literary Festival was the brainchild of Willy Dalrymple and his colleagues from Delhi. Willy writes marvellous books on Indian history but he also knows how to throw a party. At Jaipur the parties are quite legendary, with painted elephants at the gates, fire-eaters, camel-lancers on parade, and infectious Rajasthani music that makes everyone want to leap up and dance. In between all that there is serious discussion about books that draws crowds in their thousands. It is free to the public, who flock to the talks and discussions that take place on every possible subject. I shall be there in January, and am counting the days to the firing of the starting pistol.

The High Life

After Jaipur, my wife and I are travelling on to Nepal, a country I have never visited before. We are going there to see the activities of the Gurkha Welfare Trust, a charity I have been involved with on various occasions. They have invited us to see what they do in the remote villages where they look after the needs of retired Gurkha servicemen – and Gurkha families in general. The whole story of the Gurkhas is a rather moving example of oldfashioned loyalty that has survived historical change – something that is good to think about in these uncertain times. I shall also do a bit of trekking, but only a small bit. ‘Only two hours a day,’ they assured me. ‘And not very steep. Very gentle.’ Steep and gentle are relative terms. We shall see.

This article originally appeared in issue 66 of Spear’s magazine. Click here to buy.