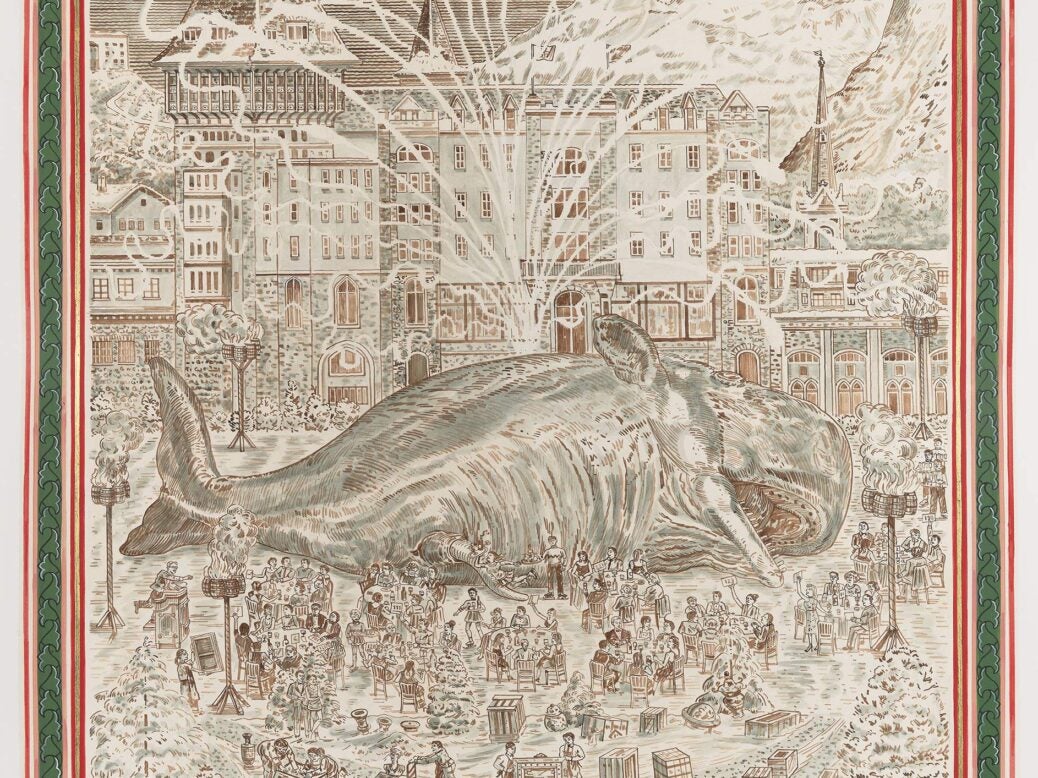

Adam Dant delightfully satirises the ‘Domus Aurea’ that is Annabel’s and the gentrification of Chelsea in the artist’s latest series of sepia ink drawings

‘The Gilded Desert’ was a phrase coined by the designer May Morris in 1917 to describe the newly gentrified environs of London’s Chelsea. Though it requires a severe stretch of the imagination to consider anything in London’s most recently vacated artistic nursery of Shoreditch as remotely bejeweled, this famously feted neighbourhood has, like most of the bits of central London where people used to ‘do’ and ‘make’ things, become an Eldorado for the leisure-wear clad idle.

People who would have been called Eurotrash before the banking, taxation and other national travails of these Mediterranean EU net-beneficiaries forced their exile to the capital, drape themselves all over my street corner coffee bar, a cloud of white cashmere in winter and loafers with tiny socks slightly showing in the summer.

Where once I’d open the door of my soon-to-be-bulldozed studio to find the burnt-out carcass of a joyridden Twingo, nowadays it’s my new neighbour’s sleek Tesla idling outside. They’ve opened an unwholesomely expensive fashion boutique in the former printers warehouse next door to me and appear to sustain themselves on the four, maybe five hedge-fund wives and art consultants who drift through their edgy, modish portals every weekday.

May Morris’s recollection of the quiet but creatively pulsing hive of Craft and Creation on Cheyne Row, when pitted against the presumed langour of indolent newcomers, struck a very pertinent chord with me as I considered the transformation of my neighbourhood reaching its apogee with the imminent opening of a Cecconi’s restaurant in the former pork factory round the corner.

I had been working, with the curative touch of Carolyn Miner at Robilant + Voena, on the idea of creating a series of drawings which represented the realm of ‘The Haute-Monde’ as a quasi-allegorical landscape, in the same vernacular fashion that 16th century Flemish artists depicted scenes from the gospels and classical myth. Places such as Mustique, St Moritz or the Buddha lounge at Annabel’s nightclub are the hang outs of the bountiful and the beautiful who, all high cheekbones, pleated silk, and ocelot might appear as if they’d stepped from the courtly medieval narrative of a pre-Raphaelite tapestry but wouldn’t be caught dead lubricating a clattering Jacquard loom.

The perennial antithesis between the nobility of considered toil as expressed by May Morris’s father, the socialist artist William Morris and the exquisite comforts enjoyed by his successors on Cheyne Row and Tite Street are perfectly encapsulated in the concept of ‘The Gilded Desert’. What is so awful about the rewards of noble labour to prompt so many artistic and literary expressions of opprobrium for the innocent and pleasurable act of lounging on the terrace of a $25,000 per week-villa, drinking chilled whatever whilst being fed grapes by nubile youth in liveried swimwear. Why does the ant assume that the grasshopper will starve in winter, it’s an assumption based solely on the outward absence of labour and projects.

Like most statements concerning the roots of all evil, the loss of one’s soul and giving everything away being the only route to true happiness, didactic allegories on the subject of great wealth are clearly not constructed for the benefit of the subjects of such a quasi-moral trope. On the subject of wealth, the history of visual allegory shows us that the satisfaction of the many is far more important than the education of the few. Visions of kings and nobles assailed by ridiculously grotesque, fanged and stubbly monsters familiar to any church or gallery-goer are obviously proffered for the entertainment of the temporarily bereft rather than for the kind of person who could afford to commission the rendering of such scenes.

The scenes in my latest series of drawings don’t take place in hell but rather in numerous locations that might be familiar to members of the ‘Beau-Monde’ . Places such as Saint Tropez, St Moritz and St James’s are visually recreated according to the perennial cliches, oft-spoken by concerned outsiders when passing comment on money and privilege. The timeless fascination, envy , horror, passionate expostulations and even ‘codified moralising’ generated by the very idea of excessive wealth underpin these densely considered and capricious depictions of this other world.

In the drawing Claridge’s: Pianos, the ne plus ultra of London’s luxury hotels is seen sitting atop a mountain peak as various figures struggle to lift pianos up its steep path.

The scene refers both stylistically and conceptually to the print tradition of Durer, Brueghel and Frans Floris. It is an allegory of sorts, but one informed by the generalisations of a current, amorphous moral tone, rather than the visual codes of such artistic predecessors.

Like the historical allegory’s deployment of the ultimately burdensome trappings of wealth, in this case a piano, the oft-touted desire of the culturally minded millionaire to master the instrument, but only after a mastery of the money markets has been effected , underpins the narrative. The effect of the visual narrative is supposed to be as ridiculous as remarks concerning camels, eyes of needles, and money not being able to facilitate the purchase of love.

Brueghel and his contemporaries couldn’t resist inserting random crucifixions, nativity scenes and martyrdoms into their completed sketches of alpine mountain landscapes, as if their depictions of the world were invalid or bereft without the presence of such over-arching themes. In the case of my own drawings of the world of today, and very often in the covers I draw for Spear’s, I’m always compelled, in what might in the recent past have been called a ‘post-modernist deployment’, to ‘reference’ either specifically or generally, the art, culture and landscape of the past.

In my drawing of Annabel’s, Berkeley Square, famously the only nightclub ever patronised by HRH The Queen, the historical analogy of ‘Nero’s Golden Palace’ was prompted immediately by the club’s recent move from it’s historic basement location to occupy the entire adjacent Mayfair townhouse. It was too tempting to imagine the old Annabel’s being bricked up, untouched for posterity.

Future generations might discover this opulent and historic site much in the same way that 18th century grand tourists found the abandoned subterranean ancient Roman ruins of the ‘Domus Aurea’, Nero’s Golden palace. Ironically , the scarcity of images of this super-discreet hangout of the beau monde meant piecing together a picture of the place as it had been became something of an archeological exercise. Fortunately, I had at my disposal a couple of sketchbooks in which I’d made some extremely covert drawings of the club on various nights out – along with the kind assistance of the society photographer Dafydd Jones who’d been hired to take pictures at a private party there in the 1980’s. I’ve hopefully been able to adequately recreate the nightclub, albeit draped in vines and filled with stray dogs.

While a ‘scholar in etching and engraving’ at the British School at Rome I was invited to visit the ‘Domus Aurea’. I was told to bring a torch and a gun – the former because the site had not yet been restored for touristic visits and the latter to deal with the current residents of The Golden Palace: packs of aggressive stray dogs. The dogs in my drawing of Annabel’s are more likely the pampered charges of the former clientele.

Like most observers and chroniclers of the beau monde from within, though with the safe remove the absence of a private income provides, my visits to these ‘Gilded Deserts’ always give rise to any number of imagined stories and allegories prompted by observing the comings and goings of, for example , the denizens of Zurich’s Bahnhof Strasse, or the off-duty Berkeley Square asset manager, sans socks and en famille on a self-conscious stroll around the Saint Tropez Saturday morning market.

I haven’t been to Mustique to draw , but neither have I been to the Court of Mary Tudor, which occupies Princess Margaret’s former home ‘Les Jolies Eaux’ in my drawing of the island. Now that Wilde, Whistler and Sergeant et al no longer provide Chelsea with the creative fount mourned by May Morris in her ‘Gilded Desert’, for me the terrace of Cafe Colbert in Sloane Square, past which dance a host of wealthy, well-heeled characters, is an oasis of satire.

Adam Dant’s drawings will be on exhibition at Robilant + Voena, from 5-14 September 2018