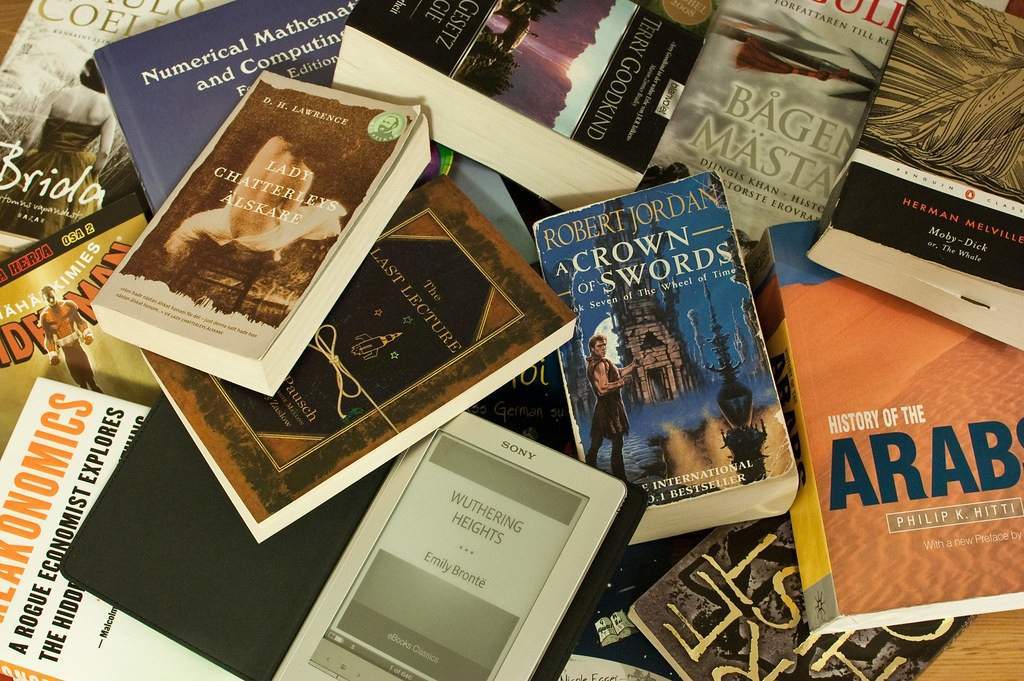

They’ve shaped our world and we still couldn’t do without them – so why on earth are books so hard to sell, asks Sam Leith

It was a book about mountain climbing, I think. Anyway, one among the 300 or so review copies of books that get sent to me every week in my role as literary editor of the Spectator. Mostly, the drill is straightforward: jiffy bag, book, press release. All easily opened and binned or, if they look specially promising, set aside to be sent out for review.

But then there are the special ones. The ones that have gone the extra mile in the hope of being noticed. Mostly these are slightly annoying: the book inside wrapped with hard-to-undo ribbon, say. Or a bunch of confetti tumbling out of the padded envelope and spilling all over the floor. Anyway, along with this forgettable – see! It didn’t work! – book about mountain-climbing, or something, was enclosed a small packet of Kendal mint cake.

Had I been an MP, I’d have had to solemnly enter the Kendal mint cake into the register of members’ interests. But I’m a book reviewer, and our ethical framework is looser. So I ate it, or half of it, and chucked the other half away, because who likes Kendal mint cake all that much anyway? Still, it got me to thinking. Perhaps this sounds ungrateful, but what I was thinking was: the book world must have the crappest bribes of any industry.

I think, for instance, about those friends who write about clothes, or make-up, or food and drink, and whose postbags groan with valuable sequinned objects, or pots and potions, or bottles of something delicious and intoxicating, and who are invited frequently to what the gossip columns call ‘glittering launches’. I think, or try not to think, of those who report on cars, luxury watches, holidays. Or those who junket regularly to New York or LA for launches of films and video games. And, readers, the Kendal mint cake is ashes in my mouth.

This is not, I should hasten to add, a plea for more extravagant bribery. Rather, it’s a reflection that the lameass-to-nonexistent bribery in the book world is reflective of the terrible way in which books are undervalued in modern civilisation. Bribes are no more than the canary in the coal mine.

The case in their favour is pretty clear. Leave aside, for a moment, the fact that without books there would pretty much be no modern civilisation. Books are our collective memory and without them, and the ability of each new generation to learn from them, we’d all still be telling each other campfire stories, scratching our furry parts and worshipping stones.

No, leave that aside (but note it all the same). Consider the present-tense case for books. They are the most incredible value for money. The price of a paperback buys you many of hours of reading pleasure and involvement. It can expand your understanding of the world or of the human heart. It can make you weep and laugh and think. And yet – as numerous book-piracy websites show us – many of us will wriggle out of spending even that. Yet we’ll unhesitatingly spend the thick end of a tenner on a fancy cup of coffee and a jambon-beurre at Pret – ten minutes’ forgettable entertainment that you can neither return to nor lend out nor, unless you’re very boring, discuss with your friends.

And apart, perhaps, from a very, very long video game, the entertainment-hours-per-pound ratio of a book is perhaps the best value of any diversion money can buy. It’s worth adding that many of the cash-showered, glamour-soaked rival forms of entertainment – movies, telly, even video games – themselves depend on books in the first place. Countless films are adaptations of books.

And we’ll spend £20 on a couple of hours in the cinema, but we won’t buy a damn hardback.

And, of course, you don’t need to look too far down the line so see that if books aren’t being bought, and writers aren’t being published, and their stories aren’t therefore available to be adapted for films, cinema tickets of the future will offer less and less return on investment. The future, to adapt Orwell, will be Jason Statham kicking a giant shark in the face… for ever. Books are what ecologists call a ‘keystone species’ in the culture.

So when I say books are good value for money, what I really mean is they are too good value for money. They’re a steal – and they are being stolen. The abolition of the Net Book Agreement (which used to fix sale prices) was good for consumers. The arrival of Amazon, with its ferocious margin-cutting, has been – at least so far – good for consumers. But what of the producers on whom they depend? Like an over-thirsty parasite, we are draining the very life from our host.

Each of these books has cost a writer many hundreds of solitary hours – Jeffrey Archer once told me he reckons it’s 1,000 hours a book. Yet did you know that, according the Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society, the median annual income for writers in the UK is now less than £10,500 – and that it’s nearly halved since 2005? That’s below the minimum wage. Let them eat cake, you say? What sort of cake? Kendal… oh, I give up.

Picture credit: Jukka Zitting @Flickr

Related

Sam Leith: Brexit novels and contemporary reference

Why I made a U-turn on luxury cars

The gentleman’s guide to rudeness