Photographer Ben Buchanan was the right man in the right place to capture the years when New York City’s art world and club scene combined magically, writes Anthony Haden-Guest

Ben Buchanan grew up in Notting Hill, the son of a specialist in art conservation, and he got hooked on photography early. ‘It was probably the only thing I was good

at school,’ he says.

He took a shot of Sid Vicious, who was in his photography class, which still pleases him. ‘That came out quite well,’ he says. ‘That was before he was in the Sex Pistols. We became friends. He wasn’t vicious at all – he was bit of a pussycat actually. But people didn’t want to sit next to him in the school café because he had greased-back hair and narrow sunglasses and leather trousers and all that. But he was quite a normal bloke, really.’

Buchanan left for New York in his late teens. ‘For a holiday,’ he says. There he took a job with the advertising department of the department store chain JC Penney, as an assistant on photoshoots. Then a friend suggested he go to California. Well, why not.

‘My visa had expired, my airplane ticket had expired,’ he says. ‘Why go backwards? Go forwards!’

A coming-of-age saga followed. Upon arrival in Los Angeles he set to calling friends of his father from the Greyhound bus station. One put him up for a few days. He then hitchhiked to San Diego to stay with a girlfriend. His first ride was offered by an affable young black guy. ‘He was in a purple Cadillac with cream leather seats. The glove compartment was stuffed with pot baggies.’ They smoked a joint, then his new pal sent him into a service station for Cokes and crisps. When he got out the Cadillac was gone, Buchanan’s things with it, passport included.

He reached San Diego, but found that his girlfriend was away skiing,

so he took to the road again, ending up in San Francisco, where he photographed a message reading: ‘ROOMATE [sic] WANTED TO SHARE APARTMENT PUNKS ONLY, SMOKING OK NO VEGETARIANS NO NERDS.’ He duly became that roommate.

San Francisco was fine. ‘I started managing bands since I didn’t have work papers,’ he says. ‘I did a show on public radio every Tuesday night for all the punk bands.’

He would run into Eric Goode, his future employer, at the San Francisco Art Institute. ‘They used to have events there,’ he says. ‘I was with a band I was managing, the Situations. One of the girls in the band married Jello Biafra from the Dead Kennedys, and I was dating the other one.’

The pull of New York was irresistible, though, so Buchanan returned, took a job with Kim Steele (a photographer who specialised in high-end corporate work), and saw a lot of artist Eric Goode, who had also moved to New York. ‘Eric was working on these small underground clubs, like one in Chelsea that was open twice a month or something,’ he says. Then Goode and some partners set about launching a club that would be a major contender: Area.

‘He wanted to make something not necessarily arty, but to have a wild factor,’ Buchanan says. ‘He asked me, “Do you want to take pictures for the rear projection screens that are

on the walls?”’

Buchanan’s true passions were rock and punk. Yes, he and a friend had visited David Hockney while he was in Los Angeles, but he admits that his interest in Contemporary art had been lukewarm. When Area opened at 157 Hudson St in Tribeca in 1983, though, Buchanan was on the team.

Area was not the only club channelling the rampant new art world energy. So too were Danceteria, Kamikaze and Club 57, and later Palladium, but Area was the most sophisticated, the most knowing, and every few weeks the space would be redone according to a theme.

‘The first theme, I think, was night,’ Buchanan says. ‘They had some real owls. And they had somebody grinding metal so that there were showers of sparks everywhere.’

Buchanan was shooting pictures of that for the on-screen slide-shows, as he was shooting all the themes, Soon, though, his duties had evolved to shooting Area’s human wildlife generally, the artists included, which wasn’t a bad place to be because the club had soon established itself not just as a piping hot club but also as an auxiliary engine of an art world rapidly picking up speed.

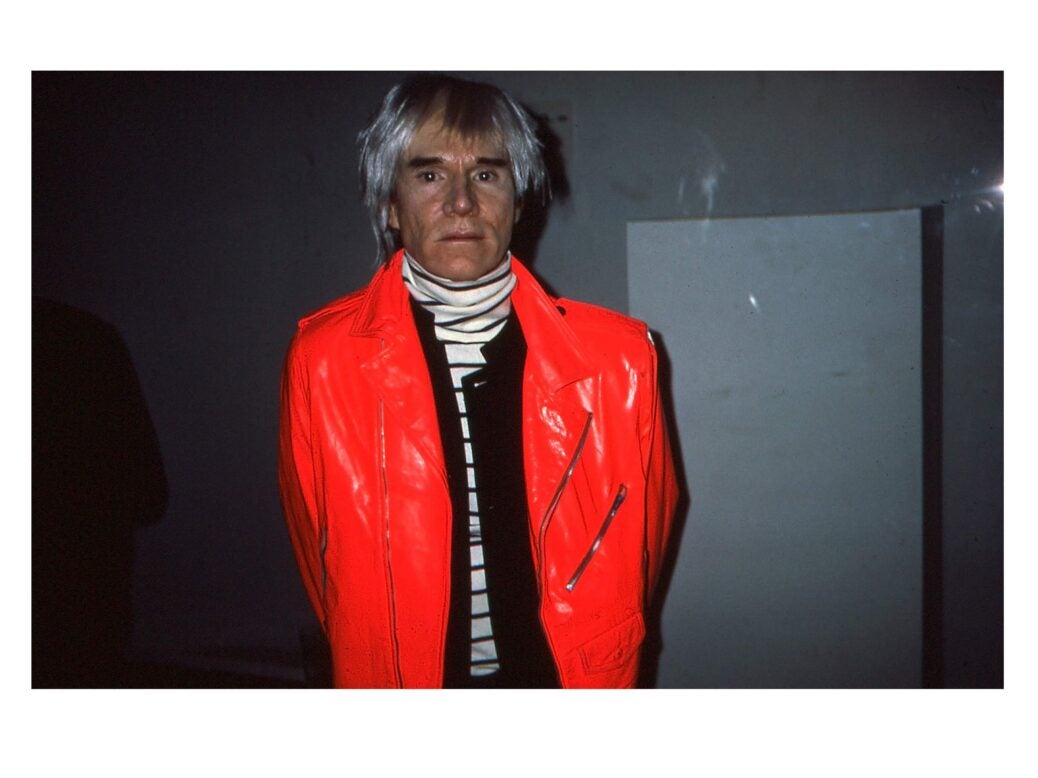

The apparition of Andy Warhol’s Invisible Sculpture, for instance, was just one nifty art notion that also seemed finely calculated for an audience with a nanosecond-long, sometimes fuddled attention span, in that it was an empty plinth standing behind glass in a room, which on the evening of the installation was also occupied by the artist himself.

‘Andy just stood behind the glass next to the plinth,’ Buchanan says. ‘As an object himself. Just to be walked past, and looked at, and tapped on the window at, and waved at. He just stood there.’ For how long? ‘I don’t know. Maybe an hour or something.’

During the second year, art itself was the Area theme, and it included the uncompromising work of Michael Heizer, a Land artist who has for the past few decades been creating one of the world’s largest artworks, in the desert outside Las Vegas. His contribution to Area was already formidable.

‘He had large meteorites,’ Buchanan says. ‘Each weighed a couple of tons. They were on the dance floor on plinths. You had to really appreciate what they were and how heavy they were.’ Keith Haring had covered a 20-metre wall of cinder blocks with graffiti in just that venue.

Buchanan got pictures of the above, as also of Jean-Michel Basquiat, who he often would speak to in the club – as he did to many of the artists. ‘Barbara Kruger did a piece there,’ he says. ‘She did a floating sign with words and dialogue going on it. And I asked her, “Can you put anything on there?” She said yes, anything! I said, “Can you put my name on it?” And she did. She put my name on it, running across the screen. She was obliging. I’ve got a picture of it.’

Buchanan was also going to openings unrelated to Area, most especially in the raw new art world on the Lower East Side.

‘I remember going to the hiphop gallery, the Fun Gallery,’ he says. ‘I got some pictures from there. And I got some pictures when they closed the doors at the end. And somebody had written: “NO MO FUN.” I think that’s where Rammellzee and K-Rob wanted to put graffiti on the whole back of my coat. And I said no! It was a Second World War German coat and it kept me warm.’

Rammellzee, who died in 2010, has recently been the subject of a huge commemorative show in Manhattan and his work is now seriously collectible. ‘I didn’t know who these guys were,’ Buchanan says. ‘I let them put graffiti behind the lapels on the front. So I had that for a few years. And then as the coat fell apart one summer day I just threw it away.’ On another evening Basquiat wanted to graffiti his shirt. ‘But that was my favourite white shirt, so I said no!’

Many people in the art world have such memories, I tell him, adding that Buchanan said he wasn’t much turned on by the Contemporary art world when he started at Area but his eyes had clearly been opened.

‘Yes. Yes!’, he agrees. ‘Well, that was the exciting thing to do. The art world was a society; they were like rock stars. So that became more interesting than rock ’n’ roll, because rock ’n’ roll was fading and getting a bit old. You know, the punk/new wave thing. So then actually the art world became a substitute for that; there was much more excitement over that. And the people seemed a bit cooler and more interesting.’

We’re talking about the early Eighties, I ask? ‘Yeah! ’83, ’84, ’85. It was where all the cool people were congregating, in galleries, at openings and at museum stuff. There were broader horizons. Bands were just five guys on a stage hammering away at something. Art was more varied. There were things to see, and hear, and touch and smell and whatever.’

He did, however, go to the last Sex Pistols concert in San Francisco. Area closed in 1987, after 30 themes. Warhol died the same year, and then Basquiat the following year.

‘After he died the estate came and took everything of Jean-Michel’s out of there. All that they left was three crates of records,’ he says. ‘So me and the people that were going to paint the place divvied up his record collection. I’ve still got some of them. Also in there were some doodles on the walls and things, and there was one I remember which didn’t get painted over. I’m thinking of waiting till they demolish everything to see

if it’s still there.’ It was still undemolished when we last spoke.

Anthony Haden-Guest is arts editor of Spear’s

Related

Meet the art-tech startup linking collectors and museums

3812 Gallery co-founder Calvin Hui: ‘I’m very confident in the London market’

Tracey Emin’s Fortnight of Tears: Review

Spear’s meets Zurab Tsereteli – the most famous artist you’ve never heard of