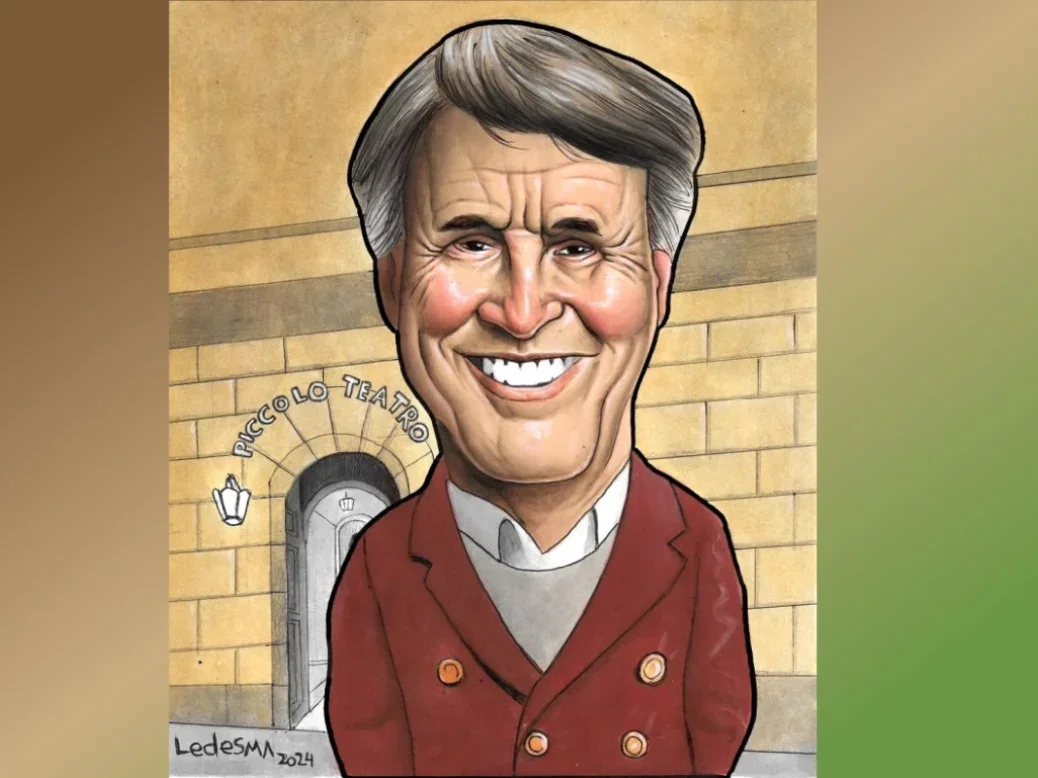

Brunello Cucinelli likes Italian cuisine as much as the cashmere clothing he makes, and for the same reasons. ‘It’s simple, of the highest quality and made here,’ he tells me, pointing to the vast steel cooking bowl overflowing with pasta that chefs from Italian Michelin-starred restaurant Da Vittorio have produced for an event Cucinelli is staging at the Piccolo Teatro in Milan, where we meet.

‘I could live on pasta, bread and oil,’ he says. His own pasta and oil, as it turns out. In Solomeo, the medieval hilltop hamlet that the designer has restored as his eponymous company’s headquarters, his team prepares pasta, risotto and locally sourced vegetables every working day. Each is served with Cucinelli’s own extra-virgin olive oil, pressed from a local cultivar. Anyone in the company can tuck in and pays less than €3 for a meal in the company restaurant (no mere canteen, here). ‘A good lunch promotes creativity and better morale for workers,’ he says.

Cucinelli has always lived and worked his values. This seems more important now, since the $250 billion-a-year fashion and luxury industry faces a winter of discontent. After years of booming sales and bumper profits following the Covid lockdowns when consumers indulged in ‘revenge spending’, many of the big labels have made a series of business and ethical missteps that have alienated customers and sent their sales and share prices tumbling.

‘It’s a big moment,’ says Cucinelli. ‘We need to find a better balance between the needs of fashion and the needs of people. The Greeks call it the “pain of the soul”. We need to heal this pain. It is the right moment for fashion to change, to move towards new times, a new world.’

‘The price is ridiculous’

Many big brands stand accused of price-gouging. The average price of luxury goods has increased by 52 per cent since 2019, according to HSBC. Some brands, including Chanel and Dior, have doubled prices of popular items. Burberry began selling T-shirts that were pricier than some offered by Hermès. The moves have ‘priced out the aspirational customer’, noted the HSBC report.

Many of the price rises are ‘absurd’, Cucinelli argues. ‘Everybody went a bit too far. Price increases are a delicate matter for customers. If a product suddenly increases in price, it can alienate them. I hear from the Italian journalists that people are tired of being mistreated.’ The industry ‘needs to go back to normal’.

His firm has increased some prices, but nowhere near as much as others. ‘We are very attentive to the market, keeping track of how customers perceive price changes. They expect value, not just higher prices. Our profit margin has stayed the same compared to 2020. ‘I don’t need an absolute profit.’

Cucinelli, whom all his staff call Brunello despite his status and 71 years, has himself felt the pinch and has adjusted his spending habits despite being a billionaire. ‘I smoke Cuban cigars. But I stopped buying them. The price is ridiculous. They used to be €32. Now they are €72! Sometimes €90!’

He does not have to skimp on clothing, of course. When we meet he is wearing a dark red double-breasted suit, with an open-neck white shirt. He fingers the hand-stitched seams and button holes to show me the quality.

[See also: Billionaires in 2024: Political profits, luxury losses and a sporting rollercoaster]

Customers are not only angry at price hikes. Some labels’ house styles have lurched from one extreme to another as designers are replaced ever faster in search of ‘the new, new thing’.

Dark and edgy Riccardo Tisci has made way for playful Daniel Lee at Burberry. Maximalist Alessandro Michele has been replaced by sober Sabato de Sarno at Gucci.

Cucinelli acknowledges that fashion ‘is in a constant state of fluctuation and we need to be prepared to adapt’. But he will not compromise on consistency in aesthetics. ‘We concentrate on customer loyalty, the relationships with our customers. It’s about trust. Trust is something that can’t be bought but must be nurtured. It’s a relationship, a personal connection. The new balance is the right style at the right price.’

High prices, low values

Bad working practices in the industry have also been exposed lately, which is especially damaging for those brands who justify their high prices by saying they have high manufacturing standards.

An investigation by Milan prosecutors, reported in The Wall Street Journal, found that one supplier had been assembling a $2,780 Dior Book tote for just $57.

A Bloomberg exposé accused LVMH-owned Loro Piana of charging $9,000 for a sweater but paying little to the community that sources the vicuña fibres it’s spun from.

Cucinelli prides himself on ethical sourcing of materials and treating his workers well. ‘There’s a shift happening and we need to take it into account.’ All his clothes are hand-made in Italy and always will be. ‘I need exclusivity and high craftsmanship.’ He pays his workers an average of about €2,100 a month.

[See also: All quiet in the great mall of China]

‘That’s 20 per cent more than the average in Italy for this kind of work,’ he says, adding that he cannot understand why other companies don’t do the same. ‘You know how much it costs me to pay my staff this handsomely? Just 1 per cent of my profitability a year.’

He describes his model as ‘contemporary capitalism… We are in the market. I want profit. But I also want the right balance in all aspects of my business.’ Revenues reached €920.2 million in the first nine months of 2024, up 12.4 per cent at current exchange rates compared with the first nine months of 2023. His business is valued at €6 billion.

Younger generations are rejecting over-consumption – the underconsumptioncore movement is strong – and many brands are not doing enough to be sustainable, critics say.

For most, the business mantra remains the same as it has always been: grow, grow, grow, and sell more, more and more. ‘That approach doesn’t work. It never worked from the beginning.’ If you grow violently, you will fail violently, Cucinelli says.

What is an acceptable growth rate for a fashion maison and the industry in general, I ask. ‘I will say that our industry has a sustainable growth of 10 per cent. It’s correct. We need moral and spiritual sustainability with our people, our craftsmen and women and our customers.’

‘You British make very beautiful things.’

His personal consumption habits are not always the greenest. Give him half a chance and he will talk for hours about his love of British cars.

‘I have a Jaguar, a 1963 E-Type. English white with a red leather interior. I have a Bentley Continental. Bellissima!’ He has a Rolls-Royce Cullinan SUV, too. ‘I used to dream of Rolls-Royce as a child. You British make very beautiful things.’ He loves his Rolls-Royce’s combination of high-tech engineering with an old fashioned analogue cabin with rotary and toggle switches and organ stop controls on the air vents.

‘It’s very advanced but also a very gentle human experience. It’s the right combination of man and technology.’

Cucinelli’s business ethics extend to financial arrangements. In recent years some of the biggest Italian brands have been accused of using elaborate international corporate structures to evade tax. He wants none of that. ‘I am Italian and my production line and factory are Italian. I need to pay my taxes in Italy. For my sons, my grandsons, for everybody who will come in the future. There is a balance between profit and giving back.’

The cashmere elephant in the room

His daughters, Camilla and Carolina, and their husbands, Riccardo and Alessio, all work in the family business and live in handsome homes with their children, a few yards away from Cucinelli.

The sharpest decline in luxury spending lately has been in China, once the engine of the luxury goods industry, due to slowing economic growth and a slump in the housing market. The downturn is exacerbated by a clampdown on ostentation led by Communist Party leaders. Social media influencers who showed off their lavish lifestyle have been banned from Chinese platforms.

‘Once materialism starts spreading, it can have a bad influence on teenagers. This trend of luxury on the internet needs to be stopped,’ state media said recently. Things are so bad that Harvey Nichols is closing one of its two stores in downtown Hong Kong.

Cucinelli is proud that unlike some other brands he has not over-expanded in China. There are only 16 Cucinelli boutiques in the country, compared with more than 100 for Gucci. ‘The Chinese market has stabilised. It’s very young and very connected. It’s a country where you grow the fastest and fall the fastest.’ But after a recent visit to Shanghai, he senses things are changing again. ‘It’s becoming stronger, more connected. Travel is back.’

There is a cashmere elephant in the room, of course. Even if he has not put up prices as much as other brands, Cucinelli’s clothes are by his own admission ‘very expensive’.

A sweater can cost thousands of pounds. But, as he grabs another bowl of his favourite pasta, he insists the price ‘is right. It reflects artisanality, quality. Also I choose to pay everybody well with the profit. I want to go to sleep knowing that I earned what I earned correctly. If you did something wrong to humanity during the day, you need to repent. If you do something good, be happy. I want to be happy.’

This feature first appeared in Spear’s Magazine Issue 94. Click here to subscribe