In retrospect, 2014 probably wasn’t the best year to have the UK-Russia Year of Culture. But despite political froideur, there was some cultural warmth thanks to a healthy exchange of ideas, exhibits and even the loan of an Elgin Marble from the British Museum to the Hermitage. Such cultural interactions recognise not only the importance of art in diplomacy but also the limitations of politics to transcend stalemate.

This appreciation does not extend to Iran, another partner in a frosty (if thawing) relationship, where economic sanctions targeting a nuclear programme have had serious and long-lasting implications for the Iranian art scene, damaging cultural dialogue and its ability to question and challenge the government. ‘The Western cultural and political policy is castrating itself,’ says Iranian artist ‘Amir Hosseini’ (not his real name). ‘[It should be] reaching out to the Iranian public, to those who are, and were always, the bridge between Iran and the outside world.’ Originally from Iran, Hosseini is now based in Europe, where he has built a successful career as an artist, joining other émigré artists such as Shirazeh Houshiary and Shirin Neshat. (Houshiary left before the revolution in 1979.)

But for those artists who can’t leave Iran, whether because they lack resources or permission, those sanctions have had practical implications. Imports have been severely limited: Hosseini remembers the price of photographic film doubling while he was studying, and when he left you couldn’t get any. Art materials are reported to be generally four to ten times the price of what they are in the UK, further compounded by the fact that art teachers earn on average £200-300 a month. Artists suffer further because of the ban on Americans importing from Iran: ‘Art you can’t take to the US isn’t killed, but it’s neutered,’ says one source.

The actual aesthetic of Iranian paintings has also been limited, dimmed by the inability to import certain metal salts that are used to brighten paints. There are stories of artists’ friends having to pack kilograms of oil paints in their luggage when returning from abroad.

A more indirect effect has been on the Iranian art market. Sanctions have made it easy to manipulate as certain channels outside the embargo are now very lucrative. Many sales are done through Dubai because art can then be sold to American buyers unable to import directly from Iran. Such movements are indicative of the convoluted, opaque market the sanctions have created.

‘Censorship’, by Katayoun Karami, courtesy of the artist and Mojdeh Art Gallery Tehran

Highlighting the perversity the sanctions have created is a rash of surreptitious dealings, fakes and smuggling. In 2013 a 2,700-year-old Persian silver griffin chalice, originally seized by US customs as contraband, was given as a diplomatic gift to Iranian president Hassan Rouhani. It has now been denounced by experts in both Iran and the US as a fake just a few decades old.

Semantic loopholes are another way to import into the US. Many pieces are redefined as ‘educational objects’, which arguably they are, but there are even further stretches possible. An art adviser based in London revealed that the demand to bypass the sanctions has drawn on existing clandestine practices for dealing with historic Middle Eastern artefacts. One approach is to get an Iranian piece to Turkey and then label it as ‘Ottoman’ to fool US authorities. Another is simply to attribute a non-Iranian artist to a piece whose real author has been lost in antiquity.

The silver griffin incident epitomises the counter-productivity of the sanctions and how they have allowed confusion to trump comprehension. There has been a skewing of legitimacy as indirect payment and shipping encourage indirect sales and anunregulated shadow market. That in turn has scared away the assistance or even participation of legitimate institutions – most notably major international banks, at least eight of which have been given fines totalling billions of dollars for breaking sanction rules.

These rules are different in Europe and the US and so, understandably, any financial facilitation to do with Iran is internally regulated in case it crosses one of several lines. Such internal regulation often involves stamping on the serpent’s egg: London-based art dealer Janet Rady had her account closed by one bank and was refused service by two others because she wanted to send money to Iran to pay artists. ‘They’re confusing it. Yes, there are financial restrictions on sending money to Iran, and we all know that, but they are refusing to open the bank account for me because I’m doing trade in Iran – but it’s in an allowed product [art].’

There are other paradoxes, too, as the sanctions have put stress on the ability of artists to satirise the state: ‘Thanks to the Western sanctions this is not happening any more,’ says Hosseini. ‘Not even like it was ten years ago. We were the Trojan horses in society. Often, when I go back, I lecture underground, I exhibit in a private gallery at a quarter the cost I would in Europe, but when people can’t afford it I won’t do it any more.’

Outside Iran, the sanctions are encouraging an intellectual dislocation between art in Iran and the ‘Iranian art’ the world sees. Experts and professionals have largely left the country for more lucrative pastures and there is now an expectation for orientalised facsimiles. ‘Everywhere I go in London I think, “Who brought this Iranian artist here?”‘ says Hosseini. ‘You do not need to be Iranian to recognise this art is a piece of horrible university homework.’

That has impacted on Iranian art’s ability to inform and educate Western perceptions, not least in the media: ‘For a long time people confused Iraq and Iran and surprisingly still do. I was featured on a very reputable website recently and they had made that error,’ says the London-based Iranian artist Maryam Hashemi. ‘The voices from Iran are very rarely featured on mainstream media and what is portrayed is a generic Islamic identity that could apply to any Middle Eastern culture.’

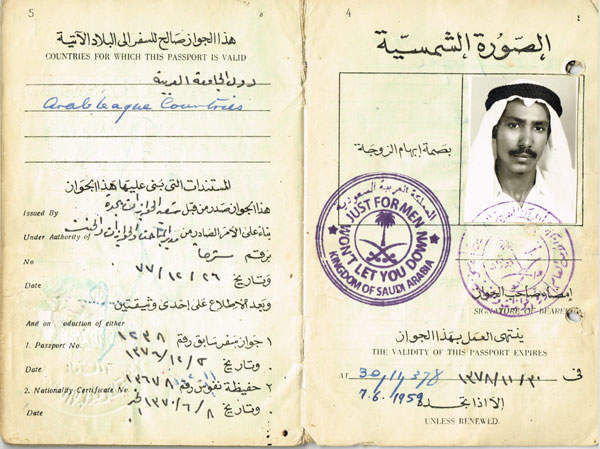

‘Saudi Passport 2’, by Soheila Sokhanvari, courtesy of the artist

Back in Iran, that means the orientalising continues. ‘Imagine eighteen-year-olds witnessing sanctions at the same time as Christie’s and Sotheby’s are [selling] Iranian art,’ says Hosseini. ‘They realise that maybe they should not really learn drawing and art history, they can just paint some exotic arabesque calligraphy and sell it.’ Iranian émigré and Bafta-nominated film-maker Tina Gharavi agrees: ‘We’re not valuing the political nature of art. The economies are pressing on Iranians to be more stylised and aesthetic, rather than challenging a system.’

The contrast between Russian and Iranian cultural relations seems stark. While sanctions have emphasised the role of art in the UK-Russia relationship, they have detracted from it in Iran, so much so that another London-based Iranian artist, Soheila Sokhanvari, drew ironic parallels between the sanctions and Tehran’s own illiberal limits when speaking at Asia House in November: ‘Artists are the lungs and voices of a culture. If you put them against censorship and sanctions, all you are doing is silencing and gagging those voices and you end up removing chances of democracy from a whole culture.’

Pictured top: ‘Untitled’ by Manouchehr Niazi, courtesy of the artist and Mojdeh Art Gallery Tehran