There is a familiar strangeness in the third floor rooms of the Ashmolean. In a museum chronicling the stories of anthropology, the drumbeats of sex and death are rarely unheard. Unsurprisingly such beats echo with an unnerving constant clarity throughout the Bacon/Moore: Flesh and Bone exhibition being held here until 19 January. It is a small arena in which to comprehend such giants of 20th century art. They complement and contrast in equal measure, both offering different vantage points and providing the coordinates for a window on the 20th century as decorative as it is devastating.

The exhibit opens unabashedly claiming: ‘Their careers were not critically linked until now,’ a statement written large on a wall directly opposite a case of 50-year-old press cuttings critically linking their careers. Despite such misplaced bravado pretending there is something novel in a joint exhibition, the primary room provides an intriguing and honest attempt at unravelling their respective processes rendering the human form on canvas and in bronze.

Read more on art and collecting from Spear’s

Francis Bacon’s Henrietta Moraes (1963) resembles two forms blended to create a cyborg of dark matter opposite Henry Moore’s Falling Warrior (1956-7). There is clearly a connection between the forms but the free movement and floating nature of Moore’s departing warrior jars against Bacon’s figures. Bacon’s seem more vulnerable, there is not the apparent conversation in many nude works by artists such as Lucian Freud, the figures are on mattresses in corners, their recoil evident in form and facelessness, contorted self conflicts, a suggestion of movement hinting this is no passive journey but forced and unwanted (potentially violent). Moore’s Falling Warrior holds the moment in its action, while Bacon denies his subjects the nature of gravity to excuse natural or even traditional Falls.

Pictured above: Clash of the titans: ‘King and Queen’ (1952-3) by Henry Moore and ‘Lying Figure in a Mirror’ (1971) by Francis Bacon

Such pain has referenced roots, the curators have fittingly posted a series of Michelangelo’s studies along the side of the gallery depicting muscle-bound men broken on crosses. Poignantly the ‘Study of a Man Rising from the Ground’ (c1537) shares an invisible weight with Moore’s ‘Figure in a Shelter’ (1941). An apt segue is the inclusion of a number of small pieces by Rodin, whom Moore much admired, revealing the gauntlet willingly seized by the English apprentice in his pursuit of form, a challenge initially embraced via modernist etchings such as ‘Standing Nude’ (1924) that nods to the legacy of the English pre-Raphaelites.

A similar draftsmanship is shown in Bacon’s ‘Painting’ (1950) but again, his figure seems strangely trapped, there are lines and limits; a man’s shadow nods towards a wall of black that is undecipherable in its distance from us.

Inner turmoil

Moore’s compositions are milder and unperturbed, they seem conscious, giving Bacon’s figures an inner turmoil by contrast; a hedge grows here. Moore’s sculpture holds itself in a creativity brilliant enough to grant an abstract freedom. Undoubtedly Moore perfected this in his career, securing an enduring appeal, but, as with Bacon, his work is not without a dark matrix. The exhibition claims ‘The Helmet’ (1939-40) shows the family unit, Moore’s nascent maternalism, in protection of an inner figure.

However the aesthetic suggests a hollow face or a figure more caged than sheltered, coercion through power rather than compassion – these were the ideas of the time. ‘The Helmet’ sits among Moore’s famous shelter drawings of figures inhabiting strange new places, they scream of Pompeii and the suspended animations inherent when flesh and bone collide with hot violence from above. Haunted conferences are being held, forms morphing into unnatural scenes, these are hurt mannequins.

Bacon also bruises the subject, the under rated ‘Composition’ (1933) seems like a tortured version of Hockney’s much later ‘A Bigger Splash’ but this is a disintegration of form rather than an emphasis via managed anarchy; it is suggestive of a time, a vortex, when lives, like walls and floors, were moving – it is the existential crisis of the physical best rendered by these artists.

After the Second World War Bacon’s gestures had a hardened soul, there is present malice. ‘Head II’ (1949) is difficult and unrepentant in its mystery, a background of charcoal like stalks reminiscent of Polish forests, through which smoke moves.

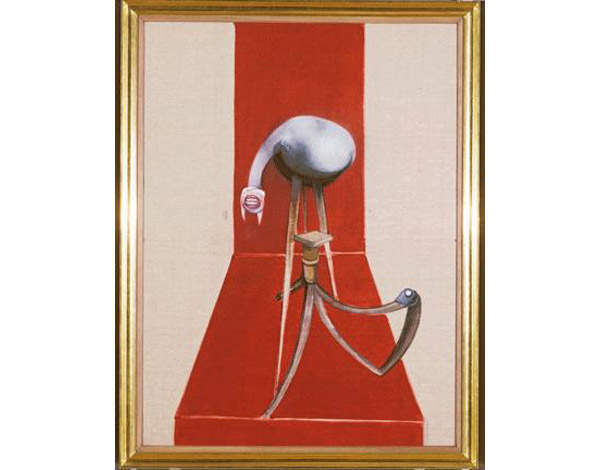

The second room holds Bacon’s ‘Second Version of Triptych’ (1944/88) (centrepiece pictured above), three frames of creatures of a very human imagination. It is the almost iconic mouth that axles the three canvases, while the left and right figures bark and bray it stays still and sinister, framing its own exposed teeth with drawn red lips. Blindfolded, atop stilts, whether a victim or a perpetrator, we cannot know but history suggests both.

Here we see Bacon’s more abstract forms, such as the ‘Triptych’ and ‘Lying Figure in a Mirror’ (1971). There is an unsettling commodity in their rounded forms, a sexual/faux erotic resonance. Twinned with the power of violence these shapes are twisted and detached on pedestals on blood red floors, framed in gold and hung high on the gallery wall – the art seeps out; it is unconfined, infectious but successful. The intoxicating catharsis beats.

And then beneath this scene lies Moore’s ‘Reclining Figure: Festival’ (1951), it too struggles to breathe outside of its icon but it is no less beautiful. Its soft, gentle curves grate against Bacon’s grimaces but converse in the movement of his bodies. ‘Two Figures’ (1975) embraces movement no less than Moore but remains boxed by dimension. Moore is able to chase an almost idealised human form that moves beyond the trite agendas of modernism and the social conceptions that had done so much to physically, and literally, pull human beings apart.

Humanism and abstract freedom

The exhibition correctly credits Moore’s humanism, moving past the war he was able to find an abstract freedom while Bacon was never happy to grant his own work such licence. Where Moore dissipates history, Bacon resonates it. Even with ‘King & Queen’ (1952-3) Moore re-imagines a touchstone of collective consciousness, and while it harbours power, it is of an entirely different nature to Bacon’s ‘Study from Portrait of Pope Innocent X’ (1965); the former is a wholly weaker piece compared to what is the stand out piece, by form and content, in the exhibition.

The third room follows on from Moore’s totemic ‘Three Upright Motives’ (1955) to demonstrate his ability with the brush to render his vision in different mediums but underlining his correct convictions that saw him triumph in sculpture. Bacon’s processes are referenced in his crucifix work, sketches, next to Moore’s, of a Picasso-like Jesus, perhaps an attempt to render a more mental process in the agenda of creed, thankfully for his sanity, something he saw as Sisyphean academic exercise rather than natural calling.

These artists do not blend in interesting comparison, so much as pillar the post-war reckoning of humanity. It would not be unfair to describe Moore’s fluid adagio being punctuated by Bacon’s poignant crescendos but that does not do this exhibition justice. In tracing their respective achievements and not deigning to authorise the war as the seminal source the exhibition succeeds in letting the pieces breathe and reference their own respective roots in the tragic truth rendered by machines of death and humanity’s willingness to employ them; Bacon undoubtedly grasps the nettle tightly but Moore’s latitude does not make him absent here. The art is important because it achieves this without explanation, flesh and bone being an apt and brave medium, one the curators have successfully credited in a powerful exhibition.

Fittingly by the exit hangs Bacon’s ‘Man Kneeling in Grass’ (1952). A strange light reveals a man, naked, on a grave. There is no escape from the incomprehension, or the consequences of the past, such is the curse that afflicted and inspired both artists; it is a grass that grows between and around these giants.