IN LOYD WE TRUST

The first communication I ever had from gastronome, former Masterchef presenter and heritage champion Loyd Grossman was — naturally — an invitation for lunch. I had written an article for The Spectator about the need for the government to tighten up its statutory protection for heritage in its draft planning framework, and within a week I was plotting with Grossman in his St James’s club, over grilled calves’ liver, about how we could get the planning minister to toughen up the measures.

On television Grossman may come across as a flamboyant Mid-Atlantic showman of the David Frost school, but — like Frost — he has a forensic eye for detail and his background is equal parts showbiz and academia, with a masters from the LSE. Indeed, had he not decided to join a British punk band who reached number 49 in the charts in December 1977 with Ain’t Doin’ Nothin’, Grossman could very easily have pursued an academic career.

Ain’t Doin’ Nothin’ actually sums up Grossman’s career quite well. He became one of the earliest foodie celebrities in the 1980s, along with Keith Floyd — but while the colourful and chaotic Floyd eventually self-destructed, Grossman used his entrepreneurial talent to become a pasta-sauce millionaire with a private office in Mayfair.

His TV break came in 1987 as a co-presenter of Through the Keyhole. When I met Grossman for lunch, he reminded me that one of his episodes had actually been snooping around with his TV crew inside the rooms of Upton Cressett Hall, my family home, when my father Bill Cash MP had been at the height of his Maastricht rebel days.

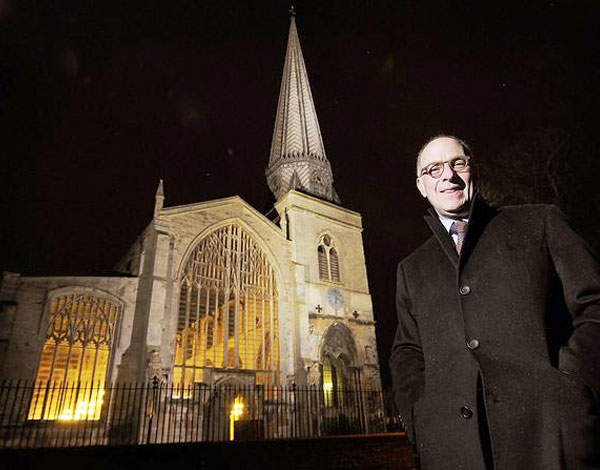

Today all Grossman’s skills are in need as the heritage world is facing its greatest financial challenge yet. With English Heritage now largely reliant on private funding, and bodies like the Churches Conservation Trust (which Grossman chairs) having had their funding slashed by 20 per cent by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, an upsurge in heritage philanthropy has never been more necessary. Nobody is better suited to raising awareness than Grossman, who is also an adviser to the DCMS philanthropy programme management board.

On 24 June, Grossman is chairing a debate in Birmingham, ‘Heritage and Philanthropy: Turning Public Passion into Pounds’. At issue is how arts, culture and heritage are ‘as important to the wellbeing of the community’ as other causes such as cancer research which are seeking financial support. ‘Accessing donors and corporate sponsors, especially outside London, is a huge challenge for heritage interests,’ he says. ‘Diminishing public funds can be devastating for not-for-profit organisations, but the vigorous heritage movement and the deep bond between people and place have huge potential.’

HIS EXCELLENCY

So how did a nice Jewish boy turned punk guitarist from a small sailing town in Essex County — that’s on the Atlantic coast in Massachusetts — end up as a clubbable éminence grise of the British heritage and philanthropy world, sitting at the high table of the conservation world with the likes of Sir Simon Jenkins and Simon Thurley?

As chairman of the Heritage Alliance, Grossman is in charge of the most powerful umbrella body in the UK heritage and conservation world, lobbying the government on behalf of almost a hundred associations, ranging from the National Trust to the Churches Conservation Trust. Not only is he Britain’s unofficial ambassador for heritage, with mobile-phone access to the likes of culture minister Ed Vaizey, but he is also an OBE who has been invited to give the keynote speech at the AGM of the Historic Houses Association.

Given all that access, he is the ideal person to ask whether the government understands how important heritage is to Britain.

LG: The government have got the message about the importance of heritage. They say good things about the value of heritage, the value of tourism, heritage’s contributions to the rural economy. But it is mostly talk. I think they believe it, and they keep telling us how wonderful heritage is and how important it is. But they’re still not providing us with the legislative framework to make it work. At the Heritage Alliance we are campaigning hard to get VAT abolished on maintenance and repair of listed buildings. As a tax it is destructive and building up a vast backlog — nearly £400 million — of much-needed repairs.

WC: Do you think such anti-heritage taxes and the general lack of progress are coalition-related? Or is it simply that the government has another agenda which is economic growth, which will always be in conflict with the need to preserve heritage and conservation?

LG: I think there are some people in the government who don’t understand how heritage is part of the economic story.

WC: The novelist Candia McWilliam — whose father Colin was an architectural historian and assistant secretary for the National Trust of Scotland — said that she has been ‘rescued’ by architecture several times in her life. Do you think an appreciation of architecture and heritage is good for the soul?

LG: Old buildings make people feel better. And being in a beautiful environment makes you feel better, gives you a sense of meaning, gives you a sense of purpose. But we also live in a society in which we make a fetish out of things that can only be valued and enumerated. Those things that can’t be quantified are treated with a certain amount of disdain and that is a tragedy for society.

WC: Do you think that because of our ancient history the English — say, as opposed to Americans — have an emotional connection to architecture and old buildings that other countries don’t have?

LG: No, I don’t think it is a peculiarly English thing. You look around Rome and you see a thousand years of architecture, all slowly growing around you. But as a nation, the British are really good at architecture. Why don’t we celebrate that skill sufficiently?

WC: Do you think the cult of the English country house has become an aesthetic fetish?

LG: I agree with Evelyn Waugh that the English country house is one of Britain’s most remarkable artistic achievements. However, I don’t think that we should fetishise one type of heritage at the expense of another. The danger with the endless English romanticisation of the country house is that sometimes it has denigrated the quality of urban life.

WC: Do you think stately homes like Blenheim or Chatsworth have almost replaced the Victorian English seaside resort as the favoured place for the retired ‘leisure classes’ to spend their time?

LG: They have certainly become mass tourist attractions in order to ensure their survivability.

WC: As chairman of the Churches Conservation Trust, what is the appeal today of visiting churches in a largely secular age? Is it more difficult to raise money for churches because churches have such a different meaning to communities today from, say, in the 15th or 16th century?

LG: I don’t think so. I think we crave something to belong to. The parish church in so many places predates the Big House. It is the parish church that historically always has been the most beautiful, the most impressive, the most aspirational in the country. We look after around 340 churches in the Churches Conservation Trust and in many of them our numbers just keep going up. We can’t always explain why. The church is returning as the hub of the community. Many people are simply drawn to sacred places.

WC: Do you think heritage tourism and philanthropy need to focus on Russians, Chinese and other international visitors — rather than just the stereotypical rich Americans? Or do you think the cultural divide is just too great?

LG: Well, the American love affair with England and its class system is very much back on thanks to Downton Abbey. A lot of the appeal of TV shows like Upstairs, Downstairs and Downton is that the shows are etiquette pornography. People watching are obsessed with whether a footman really did wear gloves to serve dinner and all that sort of crap. Class etiquette is always an object of fascination to people.

WC: Do you think the rather measly £80 million that chancellor George Osborne has handed English Heritage to kick-start its new private funding arm is going to last long? Is it a realistic amount? £80 million is what it can cost just to

save a Titian or two.

LG: The government has poured money into the arts over the years and money has gone away from heritage, and that’s the paradox. As the government spends less and less on heritage, we in the heritage sector produce better and better results. The question is, are we living in a fool’s paradise? But that is the paradox we have to live with.

Past master

With an urgent need for heritage philanthropists to step forward, Grossman is touring Britain with a philanthropy awareness roadshow of ‘heritage debates’. One of his first debates, back in 2012, was in Cambridge and asked ‘Who needs whom?’. The debate investigated whether heritage was being compromised by being understood as simply an extension of the tourism industry and came on the 25th anniversary of the publication of Robert Hewison’s depressing study, The Heritage Industry: Britain in a Climate of Decline.

More than a quarter of a century after this controversial book, the fact that the heritage industry last year contributed over £5 billion more to the economy than Osborne was expecting shows how lucky Britain has been to have such heritage crusaders as Grossman. Thank goodness he hung up that punk guitar.