UNIVERSITY CHALLENGED

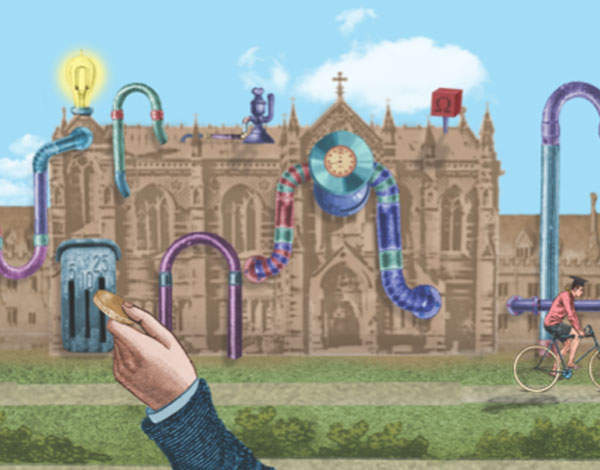

AC Grayling’s New College of the Humanities is an insurgent in a world of medieval institutions. But can it conquer its own contradictions before it takes on Oxbridge?

Sitting in the Master’s office in front of a long-dormant fireplace, sherry glasses at the ready atop a low bookcase, ancient desk under new computer before green quadrangular vista, a visitor might be forgiven for assuming that they had wound up in an Oxford college for tea and a brisk discussion of Zeno’s Paradox. That, I suspect, is exactly the impression Professor AC Grayling, founder of the new university in which we sit, would like to convey.

Everything at his New College of the Humanities, a private university a discus’s throw from the British Museum, whose air it aspires to breathe, comes with a coat of Oxford gloss. The classrooms bear studiously weighty or whimsical monikers — the Westphalian Room, the Garret, the Thinkery (taken from Aristophanes, don’t you know) — and gowns hang behind doors, ready for a professorial conclave.

Watch Josh Spero discuss school fees and social mobility

At £17,814 a year, Professor Grayling (best known for his philosophy work) is charging market rate for what elsewhere — from Oxford to Aberdeen — is subsidised to just over half that. ‘At the moment the top cap is £9,000, but that’s a supermarket price — it’s £9.99, not £10. It’s not sustainable. Everyone everywhere is squealing.

We’ve just seen the vice-chancellor of Oxford say that he wants to charge £16,000 a year. People will eventually be paying the full whack.’ He has a strong argument from private schools, where fees are (un)comfortably over £30,000 a year.

‘After all, I’ve heard colleagues and former colleagues of mine at Oxford say, “Why should Oxford be charging any less than Eton or Harrow for the education it provides?”‘

Read more on education and Boris Johnson from Spear’s

There is certainly an Oxford level of visiting professor at NCH. The likes of Niall Ferguson, Richard Dawkins and Lawrence Krauss will jet in to deliver guest lectures. (On the faculty page, there is no apparent distinction between the profs who fly in for a lecture and the full-time tutors.)

These professors have more than just a professional interest in NCH: those three — and eleven other founding professors — own a third of NCH and would ultimately share in its profits, which rather makes it seem like a potential pension plan. The rest, according to the Guardian, ‘would be owned by private investors including a couple from Switzerland who had put their own money into the venture’. So this is not just a university but also an elite investment opportunity.

Broad church

In NCH’s business model, the high costs are matched by high standards: this is no crammer for the rich and thick — yet. Professor Grayling has blended Oxford’s pedagogical methods with a North American liberal arts college, for depth and breadth. Students take a humanities major (English or economics, for example), a humanities minor, core modules in ethics, logic and scientific literacy and a careers-focused professional programme.

This seems like it involves an inordinate amount of work, and Johnny Lacey, a smart, sharp student NCH put up for interview, confirms that impression: a weekly essay for a tutorial, a weekly presentation for a small class, four hours of lectures for your major, two for your minor, another couple for the professional programme and 90 minutes for the core modules.

‘It’s very intense, he agrees, ‘and it is quite different to my friends from other universities. But I think I would always choose it, because of the development. You build up a lot of inertia and momentum in essays so the quality improves really, really fast.’

In front of the empty fireplace, Professor Grayling says he thinks there’s no trade-off between this wider curriculum and the harder work a student has to do at NCH: ‘There is only an inconsistency between being both deep and broad if you don’t have enough time to do both. We just ask the students to be both, we ask them to do more.’

When I ask whether the common criticism of NCH — that it accepts the rich and thick — is unfair, Professor Grayling retorts smilingly: ‘It’s not merely unfair, it’s an ignorant and stupid question. If anybody seriously thought that, they only need to come and look at our admissions process, the background of the students who come here and meet the students themselves.’

The requisite A-level points tally is ‘there or thereabouts with Oxford and Cambridge’, but ‘I’m personally not a great believer in grades or the A-level system, which is why we interview.’ He says that his first cohort of students in their first set of exams last summer achieved a grade and a half above the rest of the university, and Johnny Lacey and a girl we bump into studying Plato do not undermine this.

Golden ticket

To combat the perception that NCH is not for the poor, it offers generous scholarships (full remittance) and exhibitions (fees cut to £7,000) from the NCH Charitable Trust, set up with £500,000 and avid for philanthropic income. But there is a revealing moment when Professor Grayling says that they support more than a third of NCH’s students already out of their endowment.

Out of the interest or the capital?

‘Out of the capital.’

But that’s a recipe for disaster.

‘Of course it is, which is why we’re — early days, OK.’

NCH will never build up an endowment if it uses its capital, I point out redundantly.

‘That’s true, but we’re only spending the capital at the moment in order to establish the pattern, and the pattern is that some of our students pay nothing… What I’m aiming for is that once you establish this pattern, we begin to build an endowment the interest of which we can use, then we can start having a needs-blind admissions process. When I’ve got $30 billion like Harvard University, then you can all come for free!’

Despite the jokey close, this is a flighty, shaky answer. Jane Phelps, director of external relations, reflects a similar, unconscious bias to the wealthy when she talks about how students are better off being undergraduates at NCH than going to another university and having to do a Masters to reach the same intellectual level. Phelps reckons ‘there wouldn’t be spectacularly that much difference’ in fees between the two paths.

That’s still £60,000-plus, I say, but Phelps says ‘they don’t have any debt with us’ because ‘their family pays it’. Which gets to the crux of the matter. There are no student loans to cover NCH yet, so unless your family has £54,000 plus London living expenses, or NCH finds some way of continuing its generous fee support before it burns its endowment to the ground, the poor really will be cut off.

And this is where the shame lies: NCH could be just what tertiary education needs, a means of making a more rigorous education available to the thirsty (as well as an unusual illiquid investment). One must admire Professor Grayling, Oxbridge pretensions and all, because he is genuine in his desire to promote a new (old) model for study, which fits students for the modern world. But his income seems unlikely to match his ambitions any time soon.