It seems that practically every month of late art lovers have been able to rejoice as lost masterpieces have reappeared, from Nazi-looted paintings in a Munich apartment to a stolen Gauguin which had been hanging in a Sicilian kitchen. This month, a painting by post-war Italian master Lucio Fontana joins the salon des retrouvés, but its mystery is perhaps greater: it wasn’t even known that it was lost until it was found.

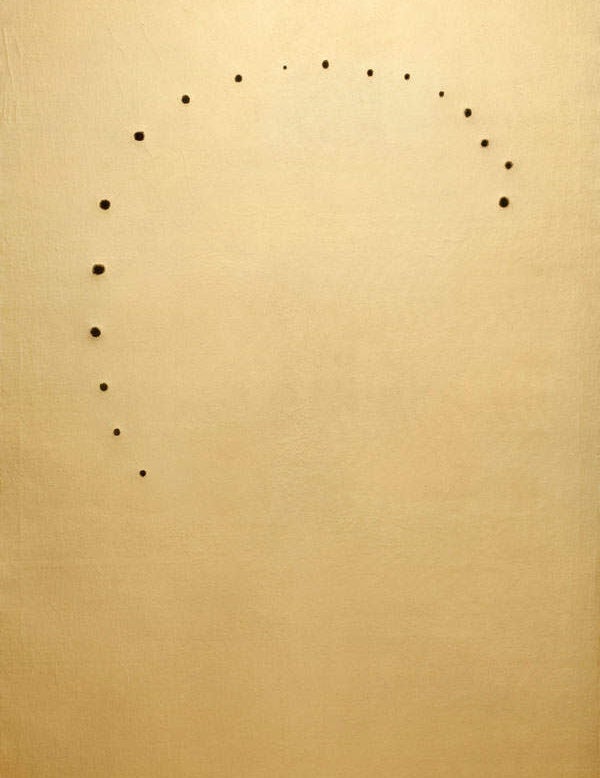

Unveiled by Tornabuoni Art in Paris last week, ‘Le Jour’ is in fact a joint effort: in 1962, Belgian artist Jef Verheyen painted a large canvas gold, then Fontana pierced it with an incomplete oval (really, more like a squashed circle). Altogether the piercings suggest a constellation astronomers never got round to naming. After it was shown by Verheyen in the Eighties in Antwerp, it disappeared, unknown to both the guardians of Fontana’s estate and fans and collectors of his work.

Fontana, born in Argentina in 1899, achieved early renown as a ceramicist in Thirties Rome, but returned to Latin America in 1940 to avoid the war. During his seven years back in Argentina before he settled again in Rome, he developed a manifesto for Spatialism:

‘We are abandoning the use of known forms of art and we are initiating the development of an art based on the unity of time and space.’ What Spatialism meant in practice for Fontana was, at first, piercing his painted canvases and later slashing them. Every work had the title ‘Concetto Spaziale’ (‘Spatial Concept’).

In the twenty years before his death, he produced over 1,500 of these cut canvases, which are currently auction-house favourites; ‘La fine di Dio’ (1963) made $18.5 million at Christie’s New York in November 2013. (My personal suspicion is that there are a lot of hedge-fund managers with Fontanas because they have both ‘wall power’ as bold-coloured canvases and brand value with their easily-recognisable slashes, and do not present much of an immediate intellectual challenge.) The discovery of a long-lost one is both an intriguing mystery and a perfect pep for prices.

Lucio Fontana , Concetto spaziale, Attese, 1966, Acrylique sur toile/Acrylic on canvas, 61 x 50cm, Courtesy Tornabuoni Art

A decade ago, Michele Casamonti, owner of Tornabuoni Art, was packing up his stand at FIAC, France’s rival to Frieze, when a collector approached him and asked him to look at what he believed was an outsized Fontana which his parents had bought.

‘I immediately rushed for all the monographs at my disposal to find a trace of its existence but none would mention a word of it,’ says Casamonti. ‘A few years later, the collector came back to inform me that the canvas had been bought in Amsterdam and originated from Belgium. We then took on the huge task of looking through all the names of galleries and merchants that no longer existed, until we came across photos of Lucio Fontana working in 1962 with the artist Jef Verheyen, which gave us a lead.’ But solid-seeming proof of the picture’s authenticity did not arrive for a few years – and then in the most unexpected way.

Usually when lost pictures turn up, there are terrific suspicions – any viewer of ‘Fake or Fortune?’ on the BBC will know this. Fraud is a significant challenge in the art market: when a potential Monet is found in an attic, no-one wants to be responsible for polluting the oeuvre of a genius or causing a collector or museum to waste millions – yet they do have an interest in reaping those millions. As the Knoedler scandal of Pollocks and Rothkos in New York has lately shown, fakes can fool experts and extort fortunes.

Fraud also undermines confidence in the broader market, a market which anyway has the sketchiest underpinnings of value. Provenance is key – a way of tracing the work back to the artist – but usually it comes by looking at gallery labels or crumbling receipts. Not here. This is a twentieth-century story.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, 1962, Huile, trous et graffitis sur toile/graffiti on punctured canvas, 116 x 89 cm, Courtesy Tornabuoni Art

Back in our century, I went to Paris last week for a dinner to celebrate the unveiling of the picture at Tornabuoni Art. The gallery has put the painting, which at two metres by nearly one and a half is exceptionally large for the artist, among twenty-odd other pieces by Fontana including smaller red slashed canvases, polychromatic pierced paintings and some of his rough-wrought but highly accomplished ceramics.

Fontana is having a moment (or, as they say in Paris, un moment). The Tornabuoni show was scheduled to coincide with a major Fontana retrospective at the Musée d’Art Moderne, his first show in France since 1987 at the Centre Pompidou. Michele Casamonti has lent a considerable number of his own pieces to the exhibition, one of whose aims is to broaden Fontana’s reputation beyond the slashes: ‘The real challenge today is to successfully convey the knowledge, unveil and share the richness of his research especially during the 1950s, beyond the iconic paintings that everybody associates with the name Fontana.’

The show is tremendously successful in this regard: I went in sceptically, expecting listless rooms full of uniform slashes, but was pleased to uncover not just the diverse vitality of the ‘Concetto Spaziale’ series but also the accomplishment of his ceramic works.

These look quite scrappy, with their thin, angular, rough-edged pieces of clay built up into harlequins or crucified Christs, then glazed in bruised purples and greens and browns, but his feeling for them is clear.

I’m not sure I esteem the ‘Concetto Spaziale’ works much more than before, though. Yes, the earlier ones show variety of colour, texture and medium, but the quite-interesting idea itself never seems to go anywhere further and with each repetition, whether on canvas or copper, becomes less of a revelation and more of a cash-in.

The two shows have the potential to broaden not just Fontana’s reputation but also his market. Tornabuoni say the rediscovered picture is not for sale, but the halo it casts on the other items in their show, as well as the academic recognition conferred by the Musée d’Art Moderne’s show, may help them fly off the wall.

Lucio Fontana, Le Jour, 1962, huile et perforations sur toile/oil and perforations on canvas, 211 x 140 cm, Courtesy Tornabuoni Art

As Michele Casamonti learnt a few months after the Verheyen connection became clear, in the archives of Jef Verheyen’s work was a video, known to the artist’s daughter but, as Casamonti says, ‘not familiar to the Fontana Foundation in Milan nor to the experts I consulted during my research’. A television channel had recorded Jef Verheyen and Lucio Fontana making the painting for a broadcast. (Can you imagine how much easier authentication would be if the South Bank Show had existed during the Renaissance?)

The video, which was played to the audience of collectors during the dinner at Tornabuoni Art, had that staid quality of Sixties television, too great a seriousness, definitively undermined by the dinner guests’ schoolboy sniggers as the presenter asked Verheyen how he felt now that his work was about to be perforated and how Fontana felt now that he was about to perforate the work. It had the po-faced ring of an old-fashioned sex-ed tape about it, an illusion not helped by Verheyen’s full beard.

The actual consummation was surprisingly quick. Fontana spent about forty seconds sizing up the canvas and tracing the arc he would take, then no sooner had he started jabbing through the canvas than he had finished. Bang, bang, bang. Eighteen in twenty seconds. I hadn’t expected it to be so quick; I had thought he would consider each hole and vary their size by mood or whim. The skill in rapidly tracing that almost-perfect arc seemed all the greater afterwards.

For proof of authenticity, there are few things more reassuring than a video of your man doing the work himself. Nevertheless, Michele Casamonti says they had an expert assessment of the work, including verification of the signature and photographic comparison of the holes. When a new Fontana appears, you have to take the pierce very seriously.

‘Lucio Fontana: Rediscovery of a Masterpiece’ runs at Tornabuoni Art, Avenue Matignon, Paris, until 21 June

‘Lucio Fontana: Retrospective’ runs at the Musée d’Art Moderne, Avenue du Président Wilson, Paris, until 24 August

Main picture courtesy Tas Filip