In an era where prices seem to determine what is good art and what isn’t, a generation of radical, recusant artists are having a revival with parachutes, X-Acto knifes and anal realisms, the market be damned. Anthony Haden-Guest reports.

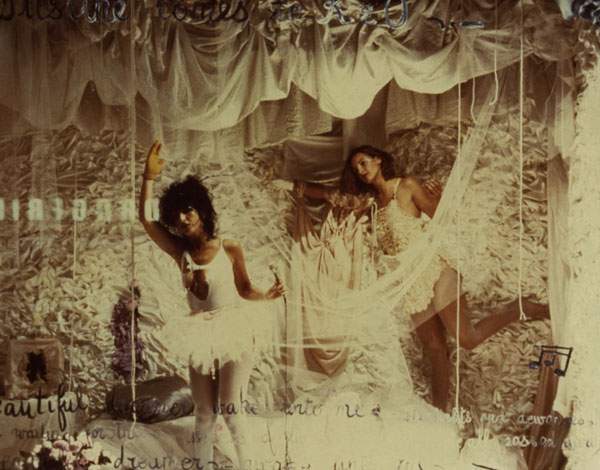

Above: Colette Lumiere stars in her own department-store art installation

It’s interesting times — that meaningful phrase — in the art world. ‘Art is the new reserve currency of the über-rich,’ Asher Edelman, who leases art and finances art transactions, told me recently. He noted that the value of the classic reserve currency, gold, has been going down since 2011. He added a caution. ‘The art is being bought by a crowd who have little time to actually look at art. So they buy what their friends are buying,’ he said. ‘Good art is not selling. What’s selling is glam.’

These new buyers don’t want to be suckers, though. In ancient times, meaning from the birth of Post-Modernism until about fifteen years ago, as movement succeeded movement, the stars of the preceding phase would usually hold long-term value. Indeed, very few market favourites from those decades have been swallowed by oblivion.

Will it be the same for the posse of abstractionists who have been the faves of collectors over the past few years and sell for anything from the middling five figures to multiple millions? They have run into a storm of critique for churning out made-for-market work and the group is under a cloud — ‘Zombie Formalism’, the phrase coined by painter/writer Walter Robinson, may be a keeper. So the B word is being heard again and crying ‘Bubble!’ is like crying ‘Wolf!’ — some day that wolf might come.

So just where is attention shifting? It is shifting, I think, to what I will simply call interesting art. For instance, increasing attention is being paid to artists recuperated from the fairly recent past, including provocateurs who began doing their stuff shortly before the Big Money began rolling in, and who were making work that was of its nature hard to buy and sell. But perhaps it shouldn’t surprise that they seem interesting just when the art economy is reflecting the 99/1 divide in the economy at large.

Colette Lumiere, a Frenchwoman born in Tunisia, is currently living in Berlin but has been a New Yorker since the early Seventies. In 1973 the artist, who prefers to be simply called Colette, used stuff like ruched parachute silk to turn her living space into a walk-in artwork, in which she naturally plays a central role.

That year her first solo show at the Stefonatty Gallery included sixteen larger-than-lifesize paintings, more or less likenesses of herself, and she morphed the gallery office into a dreamlike space in which she posed after the fashion of Henri Rousseau’s Sleeping Gypsy. And the following year she became Persephone in Persephone’s Bedroom in a parachute dress in the Norton Museum in Florida.

Colette made and makes delectable studio paintings, which are much admired, but she also made work in clubs and such public performances as sleeping in her lingerie in the window of a department store.

So a few years back she was seriously put out when she walked past the window of the hipper-than-thou department store, Barneys, on her way to a dinner party and saw that one window was occupied by a near facsimile of her signature bedroom piece, except that the mannequin at its gauzy heart did not represent the artist but the pop star Lady Gaga, and that the installation was called Gaga’s Boudoir. There was considerable media hoopla about this Pop borrowing, so it represented a loss for Colette, but mostly a win. She remains an art world presence, as do her quirky paintings.

Neke Carson is an even more resolutely anti-market artist, but he has proved an equally durable art-world figure.

Photograph above by Eileen Carson

A Texan who went to the Rhode Island School of Design and arrived in New York at the end of the Sixties, Carson has great natural skills as a painter and drawer, but he is also a manically inventive ideas man, as can be seen in his just published Works on Art and Rectal Realism.

This consists of short texts and photographs of over two dozen pieces that Carson performed in New York between 1971 and 1975. ‘Works on Art’ means just what it says. For his first piece, Time Wasting Event, he would set up a meeting with a gallery director, show them something silly he had made, record the time the meeting took, and take a photograph.

Then, when 420 West Broadway, the building which housed the Castelli and Sonnabend Galleries, opened, it was instantly the motor of what was to become SoHo, and there Carson did something even more aggravating, which was going around and sticking red dots, indicating ‘SOLD’, on every single painting, drawing and sculpture.

He wouldn’t get away with that so easily nowadays, I think, but there was an openness to the art world then, before it became a light industry. Carson, who was married and putting bread on the table designing books for Simon & Schuster, actually sold some of the red dots at between $100 and $250 apiece, usually to whoever had bought that one particular work, such as that percipient collector George Waterman.

OK, perhaps you noticed the mention of Rectal Realism earlier? In September 1972 Carson painted Andy Warhol from life with a brush inserted you know where and, by the way, he captured a recognisable likeness of his sitter.

As remarked above, Carson has great natural skills and has had an active art-making and performing career ever since. The action, incidentally, was also videotaped and the video was on permanent loop at ‘The Last Party’, a show I curated back in the summer at WhiteBox, an artspace in Manhattan.

Another artist whose overdue time is coming is another New Yorker, M Henry Jones. In his fifties, Jones is no wilful provocateur, merely an artist who has stubbornly gone his own way, managing somehow or other to remain oblivious to the mores of the art world as a game system. He arrived in New York from Buffalo in 1975 with a scholarship to the School of Visual Arts and a compulsive fascination with animation.

‘I’ve always been interested in ways of bringing inanimate objects to life,’ he says. ‘That’s why I was an animator. I liked the idea of puppets, and sleight-of-hand stuff and the optical techniques that had been developed before the first movies — these things like zoetropes and praxinoscopes that would be spun in front of a mirror to animate an image.’

It’s tech art, in fact, with a particular interest in devices from tech’s Jurassic epoch. Marcel Duchamp was just one early Modernist who paid close attention to such early technology, but what Jones brought to it was highly specific. He mentioned a short he had made, Go-Go Girl.

‘What it is, is limited animation. And what that means is animation that’s not just a narrative so much as it’s a painting in motion, an image that’s going through certain transformations. I never really felt that animation had to tell a story — I always kind of enjoyed it for its own sake, just the pleasure of appreciating it for its own sake.’

Jones’s very first photo-animation was a portrait of himself crossing the road. Think Abbey Road. It was called Walking Man. But next came 1979’s Soul City. There is often a touch of elegant fantasy to the earliest human efforts to give shape to emerging possibilities, nascent dreams.

What motorcar could ever top the Bugatti Coupe Royale of 1930? Early space modules look way more interesting than their sleeker progeny because there is a quirky DIY element there, soon to be erased when the fully evolved commercial vehicle glides in, as if the ghost is no longer needed in the machine. And Soul City is one of those rarities, an artwork that also occupies a special place in the history of technological change — in this case because the urge to create preceded the technology that would make the creation a whole lot easier.

Jones constructed his two-and-a-half-minute photo-animation of a performance by the rock group Fleshtones, enhanced with stroboscopic effects before the widespread use of computers and digitisation, and a full decade before Photoshop. His special effects were created solely through the most arduous analogue techniques.

It took nearly two years but there was an unexpected bonus: 1,700 individually printed photographs, each hand-cut with an X-Acto knife and then hand-coloured. This was the raw material for the film, reshot frame by frame with changing backgrounds.

Today these photographs stand on their own both as beautiful objects and as an artistic record of the creative toils that preceded the birth of MTV, which would be the natural home of such oeuvres, and which launched on 1 August 1981 with the words ‘Ladies and gentlemen, rock and roll!’ spoken over footage of the launches of the first space shuttle and Apollo 11. Stirring times, in short, but M Henry Jones was on the surface of that planet first.

Nor has the needle on the internal compass of Henry Jones much wobbled since. ‘The Un-Projector Show: Stroboscopic Zoetropes and 3-D Photography’, his exhibition at Donahue/Sosinski in SoHo in 1999, featured a giant pictorial Wheel of Fortune, laden with images that were populist rather than Pop, referencing Jules Verne, Barnum and Rube Goldberg rather than Andy Warhol, let alone the huge army of his sleazily worthless imitators.

Jones has always combined his tech infatuation with cartoon images, executed in his own manner, which is neither superhero-based in the classic American manner, nor does it have the look beloved of most Brit practitioners of Comic Style, which is that of a truculent adolescent.

Jones has a sweet-natured manner and even the potentially creepy elements — such as the woman who changes into a space creature and back in Molly Alien, thanks to one of his favourite media, lenticular photography — attracts rather than repels, and the cat and dog heads affixed to shields as urban trophies oddly have no morbid vibe at all.

One of Jones’s favourite characters is Slatherpuss, who came to him, name and all, in a dream and has been described as ‘an orange-billed, bug-eyed, red-and-black-winged green creature, part Loch Ness monster and part Flipper, with four orange-webbed duck feet’. Jones, in short, is channelling the culture of freaks and geeks, rather as Jeff Koons channels such nutritious terrain as balloon toys, not for sardonic commentary but for their raw vitality.

Above: M Henry Jones’s Slatherpuss flies high

As of now, moving images and 3D are his principal obsession. He continues to work with lenticular photography but is moving increasingly on to the Fly’s Eye lens, which he sees as a logical extension of the delight he found early in animation. ‘I think the Fly’s Eye photography that I’m doing now is kinda a heightened manifestation of that,’ he says. Always the compulsive tinkerer, Jones creates his own equipment

M Henry Jones has spent years working away, greatly admired by many, but far from the mainstream art world. As I write, this is changing. He has a retrospective (until 10 January) up at Gaga, aka the Garner Arts Center, a magnificent new art space in an early-19th-century former dyeworks in upstate New York. And in autumn 2016 he will be having a show at the Burchfield Penney Art Center in Buffalo. This, I feel sure, is just the beginning.

The creations of such innovative artists, provocateurs and stubborn souls who go their own way as Colette Lumiere, Neke Carson and M Henry Jones are absolutely necessary additions to the menu of an art world deluged to soddenness with work that is expertly made but doesn’t have one radical bone in its body — work, indeed, which in both its making and its pricing has more than a whiff of the salon against which the Impressionists revolted more than a century and a half ago.