Christopher Silvester on how the cotton industry shaped modern capitalism and Peter York on a daughter’s biography of one of the last upper-class eccentrics

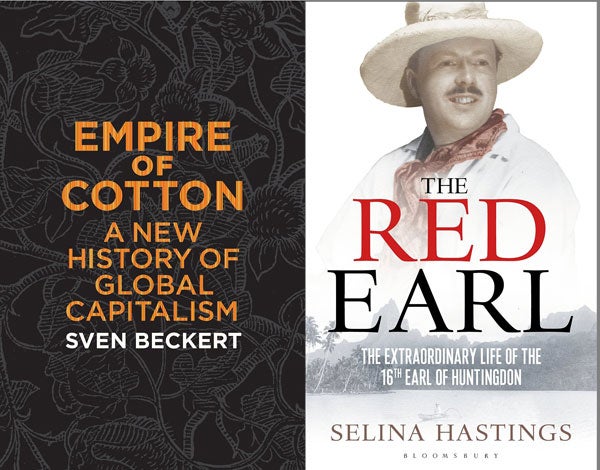

Empire of Cotton

Sven Beckert

This book announces its grand ambition in its title. It aims to be more than a history of a global commodity — one that is ubiquitous and which we take for granted in our daily lives. It aims to persuade us that the exploitation of cotton has transformed the development of capitalism in modern times far more than the exploitation of any other commodity.

The first section of the book shows how cotton was the driver behind ‘war capitalism’ (Beckert’s coinage), the system whereby European powers expropriated land by violent conquest and imported slave labour to South America, the Caribbean and the United States. At the same time, spinning and weaving based on wage labour took root in Europe and New England.

It was only after slavery was abolished in the United States that a combination of European capital and state power transformed the countryside for raw cotton production in other regions, such as India and Egypt.

Long before Chinese state-directed capitalism would transform the cotton trade once again, British colonial governments were pushing peasants towards cotton production.

In British India, for example, the colonial government encouraged the villages to focus their efforts on production of raw cotton for world markets rather than on weaving, while European piece-goods that undercut the prices of native cloth were imported to local markets via newly-built branch railways.

‘The Native weavers are exactly the class of people whom I remember in my early days on the Moor edges in the West Riding,’ wrote Secretary of State for India Charles Wood in 1863. ‘Every small farmer had 20 to 50 acres of land, and two or three looms in his house. The factories and mills destroyed all weaving of this kind, and now they are exclusively agriculturalists. Your Indian hybrids will end in the same way.’

In Egypt, cotton-growing landowners lost their estates to foreign creditors when prices fell, while the credit required to finance irrigation and rail transport eventually bankrupted the Egyptian state, which ceded sovereignty to Britain.

European domination of the empire of cotton lasted from the 1840s to the 1960s, with most power wielded not by the cotton-growing landowners or the cotton manufacturers, but by the international traders and merchants in New York, Boston, New Orleans, Charleston, Lancashire and Germany.

This was followed by a brief period during which government planners in the post-capitalist and post-colonialist societies of the global South had the upper hand. However, by the 1970s today’s new breed of cotton merchant was already emerging: the branded apparel giants and mass retailers who ‘foster competition, not just between manufacturers and growers, but among states’ and have ‘finally managed to emancipate themselves from their previous dependence on particular states’.

Cotton bound the world together like no other commodity in the 19th century, until it was superseded by oil in the 20th century.

Cotton cultivation led to the abandonment of grazing rights, to deforestation and thereby to altered patterns of rainfall; it also led to private property rights in countries where land had been communally owned and thereby to new tax bases that further encouraged participation in the global economy through yet more cotton cultivation.

Cotton trading produced new instruments of credit (exchange of bills of lading, the forerunner of the futures market) and a new culture of trust between merchants, while aggrieved cotton workers in India and China played a significant role in struggles for national independence.

This is an epic global story and Beckert, a Harvard historian, darts from one region to another with gusto and no loss of control over his material. Where he excels is in his understanding of the interconnectedness of persons and things.

In his epilogue he expresses a desire for a more ‘just world’, but he only mentions as an afterthought the benefits for all of vastly increased productivity through globalisation, and he gives no consideration to the wider benefits of modern capitalism in general.

Startlingly, there is a single passing reference to Richard Cobden and none to John Bright. Cobden was a successful calico printer and Bright inherited his father’s cotton mill, yet both were also Radical politicians who led opposition to protectionism in Victorian Britain and to slavery across the world, in spite of the latter being to the immediate disadvantage of their constituents.

Beyond his analysis, the moral purpose of the author is to demonstrate the extent to which our daily apparel has depended on the misery and poverty of others, but his case against the cotton trade is ultimately more damning of corporatism and state coercion than it is of free-market economics.

’

The Red Earl

Selina Hastings

Are English toffs ‘eccentric’? Is the idea remotely interesting in 2015? One of the more predictable tropes of old upper-class conversation is the tremendously amusing madness of family members.It’s the equivalent of that little suburban berk character in The Fast Show who was forever saying: ‘I’m mad, me!’

The subtext of those upper-class raps was almost invariably to display the longevity of family wealth, the delicious distance from the bourgeois world and their absolute self-belief and/or innocence compared with the calculating and self-conscious New Rich. It’s what sociologists call ‘legitimation’ — we’re so special, we deserve to have what we’ve got precisely because we’re not seeking it. It’s a version of Divine Right.

Generations of deferential histories and biographies have gone along with this Wodehousian notion that there is something especially fascinating about toffs’ private lives and funny musings. The spectacular waste of servant man-hours expended on useless tasks (‘he had two under-gardeners, whose only job was to…’); the amazing meals cooked whether or not anyone was there to eat them; the bird-slaughtering tallies from Edwardian shooting parties — all are presented as a Lost Art, a vanished culture of characters.

So I was distinctly wary of Selina Hastings’ The Red Earl, her biography of Jack Hastings, the 16th Earl of Huntingdon, whose cover-line premise is that this is an ‘extraordinary’ life. More funny toff stories, one thinks chippily; spare me. But Selina Hastings is a time-proven literary biographer with some major scalps — Waugh, Maugham, Mitford — to her name. And, of course, she is a toff and Jack Hastings’ daughter, brought up in the last cohort of remote, nannied Upper children, whose every experience was different from the rest of the Austerity Britain world David Kynaston describes so brilliantly in his books.

And yet, the book-jacket summary of this particular Great Life is pretty singular. Here was a 16th earl (full name Francis John Clarence Westenra Plantagenet Hastings), who managed to live a life utterly different from his father’s, ending up as a minister in Attlee’s world-changing postwar Labour government after a flirtation with communism. He also spent years working as an assistant to Diego Rivera, the Mexican communist artist who somehow became the favourite muralist of between-the-wars big American capitalism.

On the face of it, this is a case that goes beyond redundant footmen and the ‘can’t a feller have a biscuit’ stories. The problem is that Jack Hastings never comes to life as much more than a kind of upper-class Zelig here, a footnote to history. After a classic trajectory of Eton and Oxford and the Bright Young Things’ London party circuit, he makes a spectacularly unsuitable first marriage in 1925, defying his parents, especially his monstrous Australian heiress mother Maud.

She wanted a ducal family connection, a girl who would fit in and keep quiet. What she got was Cristina Casati, the difficult bohemian daughter of an Italian show-off mother, the Marchesa Casati Stampa di Soncino, a girl who liked to travel rather than hunt, preferred movie stars and caf’ society to the equine-obsessed life of the Huntingdons on their Irish estate, and was an all-round art groupie.

Once married, they set off around the world, starting in Australia and then on to Tahiti, the tiny island Moorea, and later to America. The interbellum courtship between the more aspirant bits of Hollywood and British toffs is a familiar enough story from a raft of other biographies. Jack Hastings appears to have had the Mastercard of an impending earldom, good introductions and enough money to do practically anything he wanted.

Although there’s a lot of muttering here about imminent impoverishment, both Jack and his father Warner married big money. Something absolutely always turned up that allowed Jack to Live the Life until his death in 1990.

The life he chose was a sort of global Haut Bohemia, increasingly focused on the arts. The chapter about Rivera and his wife Frida Kahlo is riveting but frustrating. You want to know so much more about why Rivera chose Hastings — hardly an obvious assistant — what he actually taught him and about Hastings’ evolution as a painter and a person.

As Selina Hastings points out, her father appears to have been monumentally shy of documentation, producing little and destroying most of it anyway (in line with the ancient idea that toffs should only be ‘covered’ when they’re hatched, matched or despatched). She calls him the Invisible Man, for all the profile his singular life achieved.

Selina Hastings was born at the end of the war to Jack Hastings’ second wife, the clever, agreeable, un-mad writer Margaret Lane. He’d divorced the unbearably tempestuous Cristina in 1943 (she married another left-wing Englishman, Lord Milford, the only member of the Communist Party ever to sit in the House of Lords).

She remembers him as distant and becalmed, by then living the traditional London-and-country life and at the same time working in the Attlee Labour government and continuing to paint. There is little enough of his work around, but the art historian Alison McClean has traced what remains. Most accessible is the hilarious Rivera-influenced 1935 mural The Worker of the Future Upsetting the Economic Chaos of the Present in the Marx Memorial Library on Clerkenwell Green in London.

Alexei Sayle said the bare-chested central figure looked distinctly homoerotic, ‘like a boyfriend of WH Auden going off to the Caf’ de Paris with Christopher Isherwood’.

The Red Earl — always well written but sometimes that bit reticent because it’s Hastings’ father — is by turns riveting and maddening for what it doesn’t deliver. The combination of track-covering and Upper Understatement leaves you wanting a fair bit more.

PS There’s one fascinating footnote. Towards the beginning of Jack and Cristina Hastings’ rebellious world tour, in 1920s Tahiti, they met the bestselling English novelist Robert Keable. Keable, once a vicar, had given up church and wife to become a writer and was by then living with a Tahitian girl. Keable criticises Hastings’ first amateurish attempts at writing, but then tries to fix him up with his London publisher. Keable, a pretty gruesome writer himself, was the love of my grandmother’s life. I’m named Peter after his 1920s hot book Simon Called Peter.