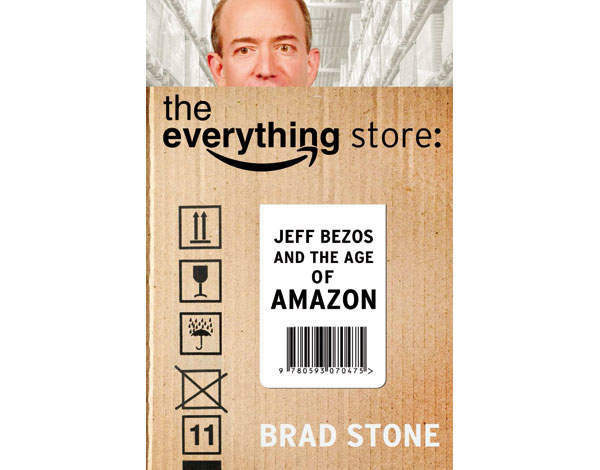

The Everything Store, Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon

Brad Stone

EX LIBRIS

Amazon know what sorts of things I read. They’re always reminding me of it. They know what I’ve bought from them — overwhelmingly books — and what I’ve price-checked with them but bought somewhere else. Their reminders say what people who bought that book also bought and, since birds of a feather flock together, they’re often right.

Amazon’s Big Data, based on real transactions, has got a perfectly good handle on my book taxonomy. Of course they understood I like business books like Brad Stone’s account of The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon. I buy a lot of that stuff. And they’ve got their bots’ minds around my love for Brit aesthetics too — great houses, garden design. Lowest price on Nicky Haslam!

And the politics, sociology, international relations. The lot. It’s fun to test them, with something wilfully obscure like Robert Keable’s 1920s novels. But you can’t win.

Read more book reviews from Spear’s here

Amazon (est. 1994) is central to modern middle-class life, one of a small group of America’s global online businesses that seem to own the future. Culturally it’s somewhere between Microsoft (1975) and Apple (1976) and later brands such as Google (1998) and Facebook (2004).

It’s not as corporate and last-days-of-old-America as Microsoft, nor as young and tactile as Google’s Larry and Sergey and Facebook’s Mark, so often seen in his pyjamas.

They’re all businesses we’ve (sort of) loved for their inventiveness and usefulness, for their daily contact. We’ve liked their (relative) New-Worldliness, their focus on cleverness and co-operation, their good design, open shirts and mountain bikes and their ability to make older businesses look stodgy or sleazy or just stupid.

And then — polling shows it — we came to hate them collectively, for their spookily Orwellian behaviour. For being every bit as commercially ruthless as any Robber Baron with a stovepipe silk hat. (Paul Babiak and Robert Hare’s brilliant book on psychopaths in the workplace, Snakes in Suits, should be recast for today as Snakes in Polo Necks and Trainers).

In the UK we’ve noticed that they don’t pay their taxes and in the US they’ve realised — because of Mr Snowden — that they’ve passed over every American’s last keystroke to the NSA.

Amazon’s particular crimes are enough to get concerned types — but not me — swearing they’ll never use them again. My friends worry about the way the price competition drives physical bookshops large and small out of business (in the US Borders is gone and the Barnes & Noble chain is enfeebled; both, ironically, in their day were seen as the scourge of independent bookshops).

They care about enfeebled publishers too. And they remain worried that Jeff Bezos can buy the Washington Post for small change.

That’s not the half of it, according to Brad Stone. I didn’t, for instance, know about Amazon’s Gazelle Project (as in a cheetah’s policy towards a small or wounded deer) regarding small competitors or collaborators. Or the 101 strong-arm instances cited in The Everything Store about Bezos — now the eighteenth richest person in the world — and his Maoist way of doing business.

Bezos’s initial policy was Get Big Fast, achieve volume and market power at the expense of practically everything: profit, employee health, conventional governance and order.

The turnover of failed ventures within Amazon — from an eBay competitor to a nappy business — and the massive churn of senior managers leave you positively exhausted. Bezos — and I think Kevin Spacey has to play him — explains it all with what Brad Stone calls ‘Jeffisms’, the easy poker-work phrases he uses on conference platforms and in TV interviews.

According to Bezos, selling at a loss for a while doesn’t matter that much because you gain market share and trust, so you’ll recoup it all later. People will see Amazon as their default provider for lowest prices and sharpest service.

Bezos founded Amazon as an online bookseller — he’d been a quant in a New York hedge fund with some distinctly Silicon Valley characteristics — because books answered the question, ‘What product categories will offer real advantages to an online retailer?’ With over 3 million titles in print, physical retailers can only offer a tiny selection.

So an online retailer with compelling links to publishers and second-hand booksellers and massive distribution logistics can give a better service to people who know what they want.

But Bezos always wanted Amazon to be the Everything Store eventually, and now it is. Books are a good brand-building way into educated middle-class budgets. And then movies and music and a sort of street market of practically everything else, with other operators and brands large and small working on the Amazon platform.

All of them, according to Stone, are watched intently by Amazon to see what performs and whether they can copy it for themselves somehow. Some suppliers who’ve decided it’s too tough and withdrawn have, so he says, found their products mysteriously still appearing, deeply discounted.

The Everything Store is riveting and thorough-going, a worthy book-end to Walter Isaacson’s biography of Apple’s Steve Jobs, but it’s heavy-going too. There’s so much churn — of people and initiatives — and Stone doesn’t keep order, doesn’t prioritise, doesn’t manage the chronology so you’re constantly wondering what year you’re in.

And, as a business reporter who’s gone from the old world — Newsweek and The New York Times — to Bloomberg, following the new tech stocks, he doesn’t come up for air enough to put the extraordinary boom and bust into the context of a changing America.

Bezos (pronounced Bay-zos) is forever talking about Amazon’s consumer service focus as justifying absolutely everything they do. But we don’t hear much about those consumers here, how they’re living and what they’re reading or who they’re voting for back there in the offline world.

There is human drama in the last chapter, where Stone discovers Bezos’s real father — a former unicyclist who runs a bike store in Arkansas. And there’s drama following publication when Mackenzie Bezos — Mrs B — reviewed The Everything Store on Amazon.com, said it was full of inaccuracies and gave it only one star.