Can you really talk about the 19th or 20th century species known as The English Collector, The French Collector or The American Collector? Or has global collecting taste become too plural to define a collector in such narrow terms?

I am about to find out over the next two days as I travel to Brussels for the 60th anniversary of the Brussels Antiques and Fine Art Fair (BRAFA) where the organisers and committee have taken the unusual step of not honouring a cultural institution or museum at the fair, but rather are celebrating the very idea of ‘The Belgian Collector’ – the very private Belgian collector that is.

The exhibition has been put together by the Baudouin Foundation, based in Brussels, and will be focusing on a series of previously largely unseen Belgian private collections that capture or typify the aesthetic essence of what makes Belgian collectors – such as Pierre and Colette Bauchau, who donated an exquisite silver ewer ornamental dish and jug that belonged to Peter Paul Rubens – different from collectors of another country.

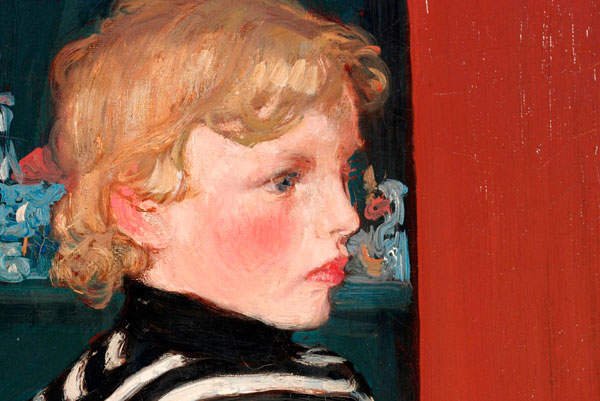

But can you talk about a Belgian collector – analysing the taste and methods of say the Belgian collectors Anne and André Leysen who have acquired the 1898 Henri Evenepoel painting ‘Charles au Jersey Rayé’ – in the same way that you might compare a Belgian chocolate with, say, Swiss, or a suit made in Naples with one made in Savile Row?

Considering that the Belgians are a country of merchants famous for their cultural and social assimilation and are also so outwardly international in their sense of self-identity, might make the notion of a national-style super collector sit at odds with today’s cultural landscape with its open cultural borders, global auction houses and specialist dealers who trot around the world proffering their wares at an ever increasing number of art circus fairs – so many indeed that one prominent old master Mayfair dealer said to me recently that he wasn’t sure why he bothered to rent a gallery space in London when the art market had become so fluid and art fair-centric.

‘You can’t pay rent for a highly visible London gallery and be at every major art fair. It’s just too expensive. You can spend £100,000 on a stand at an art fair like Masterpiece – while your gallery in Mayfair is empty. You need to sell two pictures to even break even. My clients enjoy travelling to Maastricht or Frieze Masters.’

Art dealers are increasingly like casino owners these days, relying on a few big collector clients – usually the same international clients – to see them through the year. ‘The rest of the time we are sitting in our expensive galleries trying to justify the exorbitant rent. If our clients want to see our pictures, they can come and find us on the road. In fact I think they prefer it. Your reputation and credibility is increasingly defined by which fairs you show at, not your St James’s address.’

But there is another argument – which I actually prefer – which says that it is precisely because of the rise of the blockbuster art fair and the blockbuster travelling art exhibition (watch out for the Gauguin show at the Fondation Beyeler in Basel this year) and the way that art fairs are so often a mise-en-scène of the same dealers flogging the same names to the same clients that it is refreshing to look at how a country or national collecting breed strives to keep its cultural identity.

The behind private doors private taste of important collectors is definitely one way to help define it, especially if private collections – put together over a lifetime like the Peggy Guggenheim collection in Venice – are kept intact and not broken up. There is nothing like a series of private collections that were created for aesthetic pleasure and joy, rather than commercial profit, to offer a window into a collector’s soul and a nation’s secret self-identity. At its best a private collection is more than just its parts. It works as an imaginative work of art in its own right with its own emotional lens into the joys, beauty, pain, terror, failings, triumphs, and insights into the fallibility of the human condition.

What I am looking forward to seeing at BRAFA is this eclectic emotional mix of the private collections that have been chosen by the Baudouin Foundation to illustrate the sheer range of Belgian collecting taste.

Countries that assimilate, trade and engage with the world – if you go to a Belgian dinner party in London they all speak English, not the case with a French or German – offer up a glimpse into the secrets of their private identity in their private art collections. For a Belgian, this has to include fine silverware as well.

The 1898 portrait of ‘Charles au Jersey Rayé’, which will be on show at BRAFA, is a good example of a painting that has come to be one of the most famous 19th century paintings in any Belgian collection thanks to the patronage of the children of the collectors Anne and André Leysen. Leysen, who was a vice-chairman of BMW amongst other industrial interests, is one of the most prominent Belgian business figures of the 20th century.

What is it about his purchase of this painting by the iconic Belgian-born symbolist painter Henri Evenepoel that makes the piece so very Belgian? Well, many things, not the least his extremely private choice of subjects which were invariable drawn – like ‘Charles au Jersey Rayé’ – from the children of his close friends and family. His first celebrated painting was of his own cousin called Louise in Mourning, whose own children were a favourite subject, which was shown at the 1894 Salon in Paris. Just four years later he was dead.

The Charles au Jersey Rayé’ painting depicts the eldest of Louise’s three children and is a deeply subtle and sophisticated portrayal of the secret and lost world of childhood and solitude but with a hardness that hints at tragedy, emptiness and introversion. The young boy, with hands slung in his pockets, wearing a sailor style striped jersey, looks solemn and baffled by the world. It is a brilliant study of silent introspection, an intensely private portrait that is a perfect choice to illustrate the art of the ‘silent’ Belgian collector.

In 1998, to mark the centenary of Evenepoel’s death – he died of typhoid in Paris aged just 27 – the Belgian postal service issued two stamps of this remarkable young painter’s work, including ‘Charles au Jersey Rayé’ and another painting of his sister Henriette wearing a hat.

Evenepoel was born in Brussels and learnt to paint at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts (The Royal Academy of Brussels) but like so many of his fellow countrymen who wanted to become artists, he was soon to be found in Paris.

While his early, bleak full length portraits (against a plain background) show the moody influence of James Abbott McNeill Whistler, his much bolder and brighter use of colour just a year or so later made him an avant-garde early member of the Fauvism movement. His work was influenced by painters and friends that included Matisse, Édouard Manet and Henri de Toulouse -Lautrec.

Critics often point to how ‘Charles au Jersey Rayé’ is unusual in that the portrait is of a young adult – looking out coldly and sternly at the world – rather than an innocent child. The haunting – almost defiant -portrait stands out as being a highly sophisticated and modernist composition. There is nothing naive about young Charles. We feel that he is holding onto a dark secret and that the innocent and secure world of childhood has been broken. Quite what the picture tells you about the Belgian soul, I cannot fully explain but it is a picture that celebrates the world of young self-identity and the loss of innocence with acute artistic precision.

The landmark anniversary this week of BRAFA marks the very grown up 60th anniversary of this most sophisticated of art fairs, which has traditionally launched the art fair New Year season and has a cult following amongst top dealers and high-net-worth collectors as an ‘under the radar’ must-attend event that increasingly does not live in the shadow of the better known The European Fine Art Fair Maastricht (TEFAF).

For many years the quality and competitive prices of works at BRAFA has been one of the most badly kept open secrets of the international art world, with the fair having evolved from a small but highly regarded regional antique event to a glitzy international art fair where 126 exhibitors include Old Masters and furniture and silver art is presented with modern artworks.

A final point. Admission is free to any guests travelling to Brussels, who are celebrating their own 60th birthday between 24 January and 1 February 2015.