About three years ago I was talking with the art dealer Irving Blum in London. He was venting. Blum has a track record. Most famously he gave Andy Warhol his first show as a fine artist — Campbell’s Soup Cans at $100 apiece — at Ferus, his Los Angeles gallery, but he also gave early shows to Jasper Johns, Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein, you name it. His theme was that the contribution to art history made by commercial dealers was routinely dissed, by museum folk in particular.

This was something he had thought about since the early Sixties. He had just taken the LA artist Richard Diebenkorn aboard at Ferus and was lunching with the artist’s former dealer, Paul Kantor. Blum says: ‘I was so astonished by the enormous amount of information that he had, just off the top, that I blurted out, “Jesus, Paul! You’re a resource! Do museums call you all the time?” And he looked at me and he said, “They never call me.”

‘Well, in the same way I have had a 50-year career in the art world. And I’m never called. And I know many, many dealers. And they’re never called. It’s this kind of bugaboo that dealers have a commercial interest, and have a prejudice — which is total bullshit. If a museum called me I would bend over backwards to be careful in my analysis… to be precise… and to be informative.

Pictured above: Ileana Sonnabend at her desk, circa 1965

That personal gain business is just bullshit. And that’s my point of view. But I’m informed in the art world primarily by artists and by dealers.

Museums simply don’t call. It’s a cabal of some sort. And finally, ultimately, it’s their complete loss.

‘Think of Leo in the early Sixties. Unbelievable! Was it the Museum of Modern Art that made it happen? Or was it Leo Castelli?’ (‘It’ being the establishment of who mattered in Modern art history, a resonant chronicle, traditionally ascribed to the first director of MoMA, Alfred Barr Jr.) ‘By all odds as far as I am concerned it was Leo Castelli. The museums are always late. And that is one of the reasons.’

Seller’s market

Dealers were inching towards art-historical respectability, but slowly. In 2001 the powerful London dealer Anthony d’Offay closed his gallery and sold a remarkable 725 works jointly to the Tate and the National Galleries of Scotland for way under asking price. These were organised into Artists’ Rooms and are shown nationwide. Blum organised a show around Ferus at Gagosian, New York, in 2002 and in 2009 the artist John Zinsser showed his Art Dealer Archipelagoes at the Graham Gallery in the same city.

Pictured above: Alexander Iolas painted by warhol, one of his artists

Zinsser is best known as an Abstractionist, but each of these paintings represented a gallery as an island or island group and each was inscribed with the names of some of the gallery artists, not necessarily chosen for star quality. Names on the Castelli island, for instance, include Jasper Johns, Frank Stella and Andy Warhol but also Nassos Daphnis and Salvatore Scarpetta, two of the dealer’s first artists, whose careers never achieved lift-off but to whom he typically had remained loyal until the end.

‘It’s really a show about how these New York dealers made art history,’ Zinsser told me at the time. ‘Much more than the institutions, much more than the critics. It’s the dealers that mapped out post-war American art history.’

Round the sonnabend

We are now in a time when the voice of the market has become more powerful in establishing reputation — the first draft of art history — than it has ever been, so it’s no surprise that the contribution of (certain) dealers is being further brought into the mainstream.

The most notable recent examples have been the shows at New York’s MoMA and at Venice’s Modern art museum, Ca’ Pesaro, of works that either belonged to or passed through the hands of the New York and Paris gallerist Ileana Sonnabend.

Of the two, the MoMA show had the more curious birthing. Sonnabend, former wife of Leo Castelli, had been not just a dealer but also a collector, mostly of plums she picked from her own shows. Among them was Canyon, one of Robert Rauschenberg’s signature pieces, of which the principal element is a stuffed eagle. After Sonnabend died in 2007, her collection was valued at $876 million and a tax bill for $471 million was presented. But the stuffed eagle is a bald eagle.

‘We were prevented from selling Canyon because the bald eagle is a protected species,’ says Antonio Homem, Sonnabend’s adopted son and a partner in the gallery, who now controls the estate with Castelli and Sonnabend’s daughter, Nina Sundell. ‘Logically, if you are prevented from selling something it has no commercial value and you have no taxes to pay on it.

Pictured above: The disputed ‘canyon’ by robert rauschenberg

But the IRS decided that even though you cannot sell it you have to pay taxes on it. So you find yourself in a situation in which you have to pay several millions of dollars without being able to sell what you are paying the taxes on.’

So Canyon became a gift to MoMA, which celebrated by giving the Sonnabend collection a show. Press commentary suggested this was part of the deal. Not so. ‘It was very nice of them,’ Homem says.

‘It’s a show with which I had nothing to do. Let’s say it was the vision that the museum have of Ileana, whether right or wrong. And so basically nobody else had any part in it. So let us just say that the circumstances were negative but the results were positive.’

Homem does accept other criticism aimed at the show, notably by Holland Cotter in the New York Times, which was that it showed Sonnabend’s hits and not her misses. ‘What people generally refer to as misses are things that don’t do well at auctions,’ Homem says. ‘If you say, well, she liked Rauschenberg and Lichtenstein and Warhol, well, by now everybody does. Of course Ileana did it much before. But still it’s more interesting when it gets a little more complex.’

The show at Ca’ Pesaro did include many more obscure Sonnabend artists, but it also highlighted a very modern-timesy situation. ‘It is a city museum and they did not make much of a social manifestation,’ Homem says.

‘And in Venice, as at almost all art manifestations nowadays, people only go to social occasions. So it was a show that very few people saw.’

Greek bearing gifts

A different sub-history underlies the recent show devoted to the flamboyant Greek dealer Alexander Iolas at the Kasmin Gallery in New York. The idea came to Adrian Dannatt at the Thessaloniki Biennale of Contemporary Art in 2011. A Paris-based Brit art writer and curator, Dannatt had been tossing around ideas for a project with Kasmin.

The penny dropped as he circumnavigated the sprawling Iolas donation to the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art. The name of Iolas, which had once rung bells as loudly as had Leo Castelli’s, has become a bat-squeak that only art historians can hear, but with art-world attention increasingly focusing on gallerists it was timely.

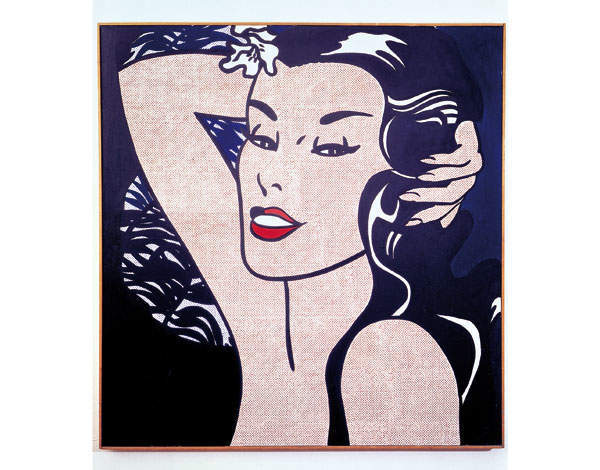

Pictured above: ‘Little aloha’ by roy lichtenstein

So Dannatt turned his attention to the Iolas archive. Castelli’s archive, several years before his death in 1999, had been valued at $2 million. It is now with the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian in Washington DC. The Ileana Sonnabend Gallery archives are with the Frick.

But Iolas had been more far-flung than either, with galleries in New York, Paris, Madrid, Milan and Geneva; significant artists he had worked closely with ran from Magritte, Max Ernst and Warhol to Paul Thek and Ed Ruscha. So what treasures did the Iolas archives cough up?

‘Nothing!’ says Dannatt. ‘Chaos! They were complete chaos.’

He was not surprised. Nor would anybody who knew the dealer have been. As Dannatt puts it, he might have walked out of a novel or an Orson Welles movie.

To such self-created figments, archival facts are as pins to butterflies.

Better late than never

Just before the Armory Show in New York, I reconnected with Irving Blum and noted the increasing interest in the contribution of dealers to art history. He said yes, but added that Sonnabend and Iolas were dead. True, and relevant. But so is the impact of a handful of such dealers.

Others who deserve their klieg-lit moment might include London’s Annely Juda, Iris Clert in Paris and the New Yorkers Richard Bellamy (who gave early exposure to Claes Oldenburg, Donald Judd and Mark di Suvero) and Klaus Kertess. Juda, Clert and Bellamy are gone but Kertess is still with us, as is Virginia Dwan, the great LA and New York dealer about whom Germano Celant of the Fondazione Prada is writing a book.

It isn’t clear-cut, though. One museum director whose opinion I sought jumped like a startled foal and said he didn’t want to discuss the business side of the art world. I said nor did I, but he wouldn’t be drawn anyway. But, yes, there is a business element. Soon after Sonnabend’s death a substantial chunk of her collection fetched $800 million, more or less at the bottom of the post-Lehman slump.

Certainly the museum shows have added value to the remainder of the collection, now on long-term loan to Ca’ Pesaro. So it is a shadow area — but alive with possibilities.

Pictured top: Warhol’s skulls (1976) was among the works sold cheaply in 2001 by dealer Anthony d’Offay to the National Galleries of Scotland and the Tate