A fine exhibition at the Royal Academy is a new and illuminating way into the work of an artist whose reputation precedes him, writes Christopher Jackson

It’s the question always asked of the artist, often in a note of throaty awe: ‘Where do you get your inspiration from?’

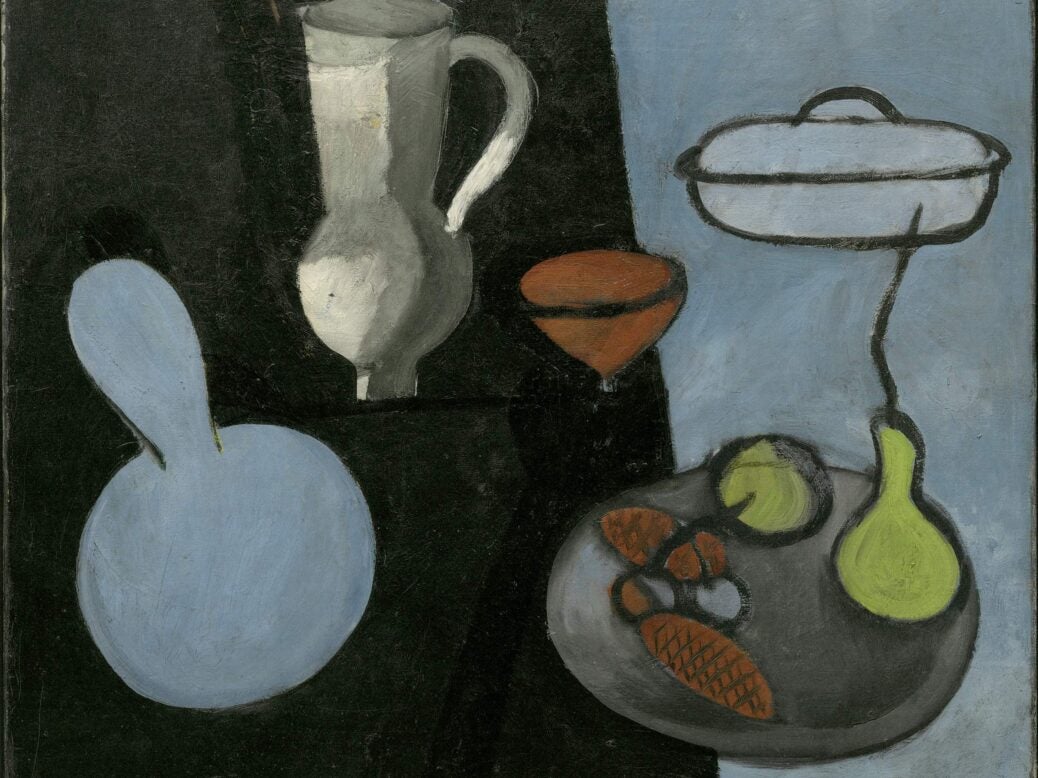

Needing to find a slant on a great name to deliver its requisite summer blockbuster, the Royal Academy has found a cunning approach regarding Henri Matisse (1869-1954). Each room shows us not just Matisse’s works, but also the objects which over a long career he collected, was influenced by, or deposited – usually much transformed – into his compositions.

Sometimes the objects themselves can seem innocuous. In the first room there’s a green Andalusian vase (below) – a slightly wonky item, whose handles resemble an affronted diva with hands on hips. It doesn’t strike one as a likely fit for Matisse’s art. But when the vase does enter his pictures – as in Safrano Roses in front of the Window (1925) (also below), it attains a special meaning – one might even say it is declared to be sacred, while having lost none of its sassy character.

Matisse’s is essentially an amorous art: this exhibition finds him falling in love with objects over and over again, and then expressing his love by reworking them in painting and sculpture. Any artist, and especially a great one, has entered into an unusually responsive relationship with reality – and this entails the continual transformation of the humdrum. I have seen the exact section of Suffolk which Constable turned into The Hay Wain, and can report that the Constable is better. Mona Lisa didn’t look like the Mona Lisa in real life: her smile isn’t hers – it’s da Vinci’s.

But there is also something of the lepidopterist about Matisse – he is compelled to kill the thing he loves. In room after room, his episodes of creation turn out to be – paradoxically and at the same time – acts of destruction. Every object is fallen in love with, picked apart, and turned into something wholly separate. For instance, a racaille chair in the second room, which Matisse fell for early-ish in his career, eventually becomes that painting of turbulent arabesque The Racaille Chair (1946) – it’s as if reality has been intensified, or even remade, by that definite article.

Sometimes, as in his sculpture La Serpentine (1909), Matisse reinvents the spatial relationship he encounters. Here, the source is a photograph of a nude woman next to a table. But in his related sculpture, Matisse gives her wider hips, and an impossibly sinuous torso, to create a void between the woman and her prop – a reminder of empty space, when the original is solely concerned with the voluptuousness of flesh.

Matisse was already on an irrevocable journey towards simplification: it is as if detail had become synonymous with fuss. As the influence of African masks was felt, Matisse sought not the circumstance but the essence of the human face. For instance, his series of Madame Jeanette sculptures shows the subject becoming gradually less feminine over time. In the culminating piece, one has a strange sense of something harder, and even ungendered, poking through once all the idiosyncrasy of the feminine has been pruned. Matisse has distilled his sense of her into the blunt facts.

In Italian Woman 1916 (see below) we see this same process in infancy: the subject’s face is already masking over, and her shoulder is edited out by the gauze of that drapery. She is already in retreat from temporal quirk toward a state which makes one think – however outlandishly – of eternity.

The Italian Woman, 1916

Where did Matisse get his inspiration from? In reality, the artist is driven by inner compulsion – a wish for beauty, a fear of death, or a simple need to tinker with the world as they find it. These objects were probably incidental to a larger need driving Matisse. If it hadn’t been these, the wide world would have provided him with inspiration elsewhere.

By the end he had embarked on his great cut-out shapes – he came to exist eventually in a sort of Elysium of signs and symbols where everything unnecessary had long since been deleted from his reckoning. But he was always a Fauvist at heart, and he went out in a riot of colour and line.

He died, as we all do, surrounded by objects. But the difference was that he’d been in dialogue with them all along. And this highly original exhibition shows that, in art’s continuous realm, he still is.

Christopher Jackson is head of the Spear’s Research Unit

Recently

Review: Hokusai — Beyond the Great Wave, British Museum

Review: The Japanese House: Architecture and Life after 1945