I am endlessly staggered by the statistics around domestic violence. Research suggests it affects one in four women — that’s eight of my colleagues as I look round the office.

If one came to me and asked for support, what would I say? Well, because I work at NPC I could signpost her to organisations that offer help. But if I didn’t work here, would I know? Many women feel unsure where to turn for advice, and some don’t even realise they are in what would be classified an abusive relationship.

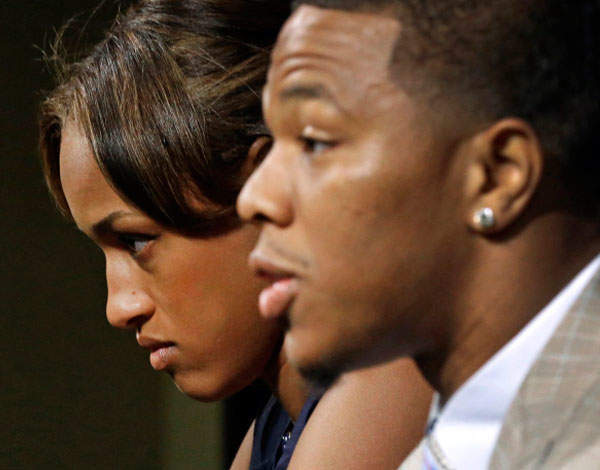

So when the spotlight shines on domestic violence, we should take the opportunity to influence as many people as we can. And that spotlight is now shining without remorse in America on the National Football League’s lenient and inadequate approach to disciplining players accused of domestic violence. Recent reports suggest that the NFL was aware for months of footage in which a player punched his wife to the ground, and did nothing.

The violence against women sector previously relied heavily on statutory funding, and deep funding cuts over the past few years have therefore hit it hard. The issue hasn’t historically appealed to many donors either, leaving an even bigger gap to fill.

Funders that want to intervene in this area confront a bewildering range of activity — from campaigning, to prevention, and the provision of safe houses and counselling services.

Clearly there is no single, correct answer about what to fund — all need money. But at NPC we believe funders should always look for evidence of impact to ensure their funding is most effective. For example, CAADA is a specialist provider of Independent Domestic Violence Advisors (IDVA) training, and collects evidence showing that 57 per cent of all victims supported by an IDVA experienced an end to abuse in the following three-four months.

Similarly, Woman’s Trust, a provider of specialist counselling to woman affected by domestic violence by women, collects CORE (Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation) and exit data demonstrating that counselling can result in improved health, increased autonomy and a better ability to function.

There is less evidence for proven approaches in early intervention, for which there is clearly a need. Research by the NSPCC found that one in four girls, some as young as thirteen, had been hit by their boyfriends.

<p>There is some proof that programmes designed to educate and support positive attitudes among at-risk young people are effective, especially in building healthy relationships and mutual respect. But more work is needed here, plus greater innovation — as recommended by a recent report by the Early Intervention Foundation.

Neither should emergency responses be overlooked. Refuge places — specialist safe houses for women and children — are desperately thin on the ground. Women’s Aid has reported a fall of around 25 per cent since 2010 in both the number of refuge places available and the number of specialist providers.

The problem is as complex as it is urgent. But as the state withdraws its funding, and wider society too willingly looks the other way, philanthropists may be the right people to step up.

Abigail Rotheroe is deputy head of the charities team at NPC