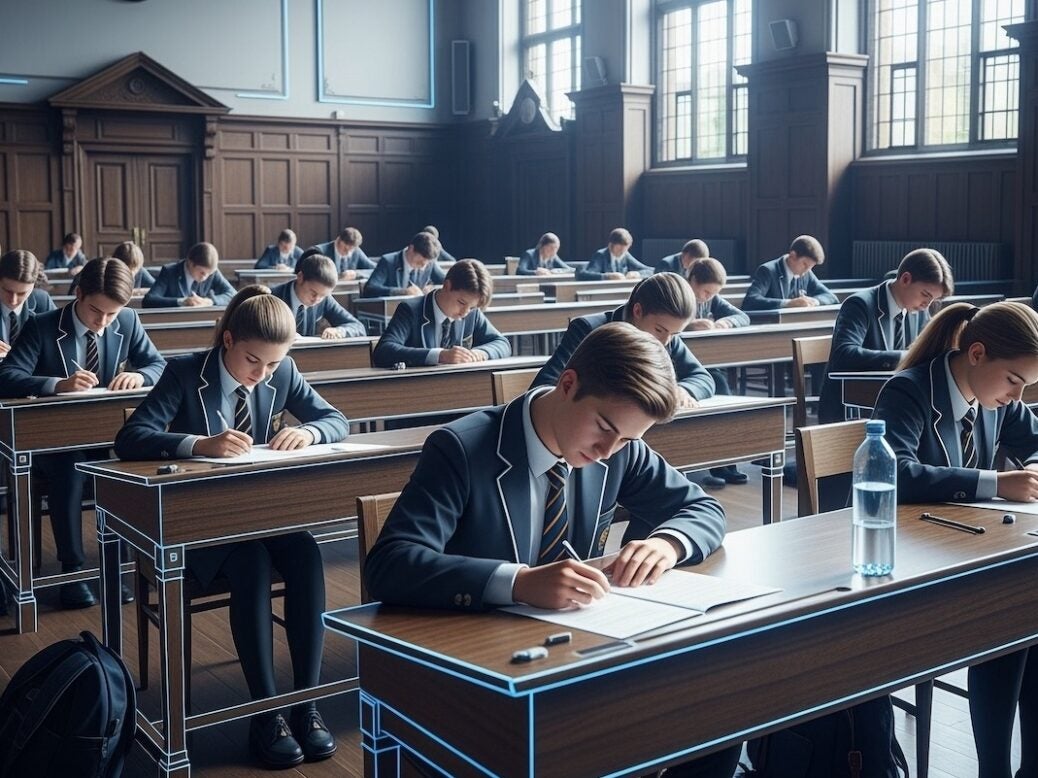

Since 1951, A Levels have been the go-to choice for students (and parents) seeking admission to prestigious UK universities and success in high-paying jobs. Tomorrow, some 821,000 members of the class of ’25 will receive their results and embark upon the rest of their lives. They deserve all the congratulations, encouragement and commiserations they will receive.

But seismic changes in society, technology, and education mean that this year’s cohort faces a quite different future from many who have gone before. And it’s time to acknowledge that A Levels are no longer fit for purpose. The most ambitious students should choose another path.

As an international educator, I’ve seen how alternative options such as the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme (IB DP) and US Advanced Placement (AP) courses offer a better route at time when AI and other factors are transforming the nature of work and study. (The Spear’s Schools Index details which top global private schools offer each type of programme.)

IB alumni include Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, Booker Prize winner Anne Enright, Oscar-winning actress Lupita Nyong’o and Facebook (now Meta) cofounder Dustin Moskovitz, whose net worth is estimated to exceed $14 billion. Ambitious and globally mobile families should think beyond Britain’s academically limiting secondary school qualifications.

[See also: How to get your child into private school in the UK: the expert guide]

Employers want well-rounded individuals

With most students taking only three subjects, A Levels hark back to a time when deep but relatively narrow specialist knowledge was the key to professional and economic success. But modern workplaces require a broad knowledge base and a range of durable skills which go beyond memorised facts and calculations.

Qualifications such as the IB DP, which requires six subjects in addition to three core components, prepare students for an increasingly interdisciplinary workplace. For AP, most students undertake four to six courses, studying university-level material with external examinations that are every bit as rigorous as A Levels (and more). This balanced education buffers students against rapid technological change, preparing them to thrive across working lifetimes that are likely to span multiple, often widely-divergent careers.

IB and AP courses encourage students to contextualise their learning within the real world. IB assessments require students to apply their learning to new situations, reflecting authentic contexts that value critical and creative thinking over brute revision. Both courses require extended independent research, producing confident and resilient learners for whom knowledge is more than just academic. IB and AP diploma graduates learn to do what AI cannot, at least not yet anyway. And they build the very human skills and attitudes that machines are not equipped to provide—or which we are likely to reserve for ourselves.

[See also: Should you send your child to an elite boarding school?]

A Levels restrict students’ potential

A talent for memorising broad swathes of information does not make a future leader, and one needs only look at the long list of successful people with less-than-stellar A Level results to see that they are hardly the gold standard for measuring potential. Many brilliant young people experience a needless setback on their journey to success because their talents lie beyond what A Levels examinations can assess. This can leave those who succeed in A Levels underprepared for later life, while many who excel in other areas have no opportunity to showcase what they can do. The interdisciplinary, practical approach encouraged by IB and AP qualifications does not just give students a broader knowledge base – it enables everybody’s talents to shine and encourages students to develop skills which will help them make a real difference in the world.

Are students who last learned about history, mathematics, or science when they were 16 years old —an age where critical adult thinking is not even developmentally possible for many adolescents – really going to be prepared for what’s to come?

The world is changing, but A Levels haven’t

In a world of generative AI, forcing young people through an education system designed before the invention of the internet seems nonsensical. Unlike A Levels, which are still primarily delivered through written examinations, the IB has offered digital assessment for its Middle Years Programme (equivalent to GCSEs) since 2016 and is moving towards digital examinations for the DP. Likewise, AP introduced their first digital examinations in 2023, with a full transition to online tests made in May this year. These onscreen examinations open new ways of assessing students’ real-world skills and their ability to transfer knowledge to unfamiliar situations. By engaging students’ digital competence, these forward-thinking qualifications make combining knowledge with technology second nature when problem solving – a vital skill for the modern world.

These qualifications are made for the modern world. With AI driving concerns about misinformation and authenticity, it’s more important than ever to help students develop sophisticated competence in digital literacy and critical thinking. The advent of the internet has brought a boom in misinformation. The IB is designed for that – the DP Theory of Knowledge course encourages students to evaluate knowledge critically, not only by asking questions but also questioning answers. This unique course encourages students to reflect on the nature of knowledge and how we know what we claim to know.

[See also: Billionaire parents go to war with the world’s most expensive school]

Alternative options shape global citizens

As the world becomes increasingly interconnected, opportunities for students with advanced academic potential are no longer limited to the UK’s outdated educational system. As a network of international schools (ACS), we are particularly aware of the importance of global perspectives, and we are constantly looking for ways to prepare students to take their place among the leaders of local, national, and international communities.

IB and AP courses are adaptable and purposefully revised on a regular schedule of curriculum review. Teachers choose from diverse, multilingual, up-to-date materials and real-world case studies from students’ local communities and the wider world. These qualifications are not subject to political whims of a single national government, but rather rely on an international pool of educators and university advisors to ensure that they remain relevant and responsive to the ever-expanding scope of traditional and contemporary academic disciplines.

[See also: VAT on private school fees driving HNW ‘exodus’ from the UK]

A Level students perform worse at university

A Levels are supposed to prepare students for university, but the academic grounding provided by international qualifications often proves more rigorous in important ways. For example, extensive high-quality research by International Baccelaureate has found that IB Diploma students perform well at university, being 40% more likely to obtain a first or upper second-class degree in the UK.

With AP and IB students consistently outperforming their A Level peers, globally-savvy parents should consider if a qualification that has not changed much since the days of the UNIVAC computer and the Korean War is suitable for their children.

Robert Harrison is director of education & integrated technology at ACS International Schools