Over the past couple of decades, a pattern has emerged. Every two years or so – almost like clockwork – a senior judge in the UK hits out at the spiralling legal cost of divorce, calling the fees, among other things, ‘eye-watering’, ‘staggering’ and ‘unacceptable’. What usually happens is the same judges then appeal for rule changes and a cap on charges to prevent fees – which can often be in the millions – from running to ridiculous levels.

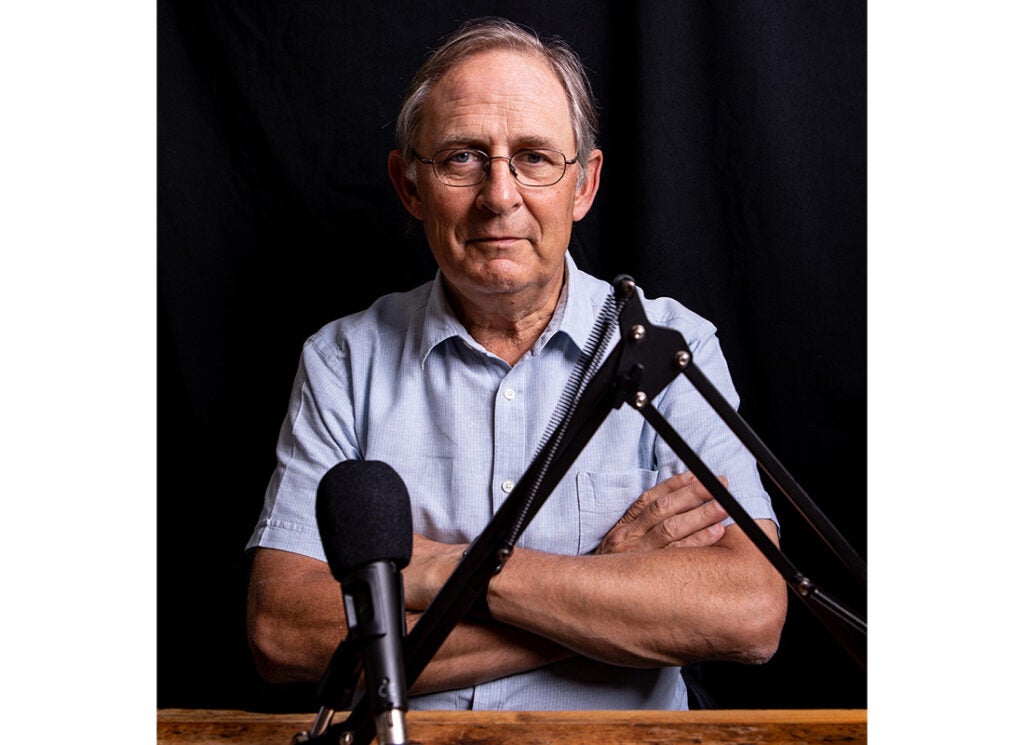

The loudest of those pleas came from the now retired high court judge Sir Nicholas Mostyn, who presided over a case in 2014 where a couple racked up almost £1 million of legal fees on a pot of wealth worth £3 million. He called it a ‘grotesque leaching of costs’.

[Spear’s Family Law Survey 2025: Experts identify core trends]

‘I must confess to have been almost lost for words when the scale of this madness was revealed to me,’ Mostyn said in his judgment at the time, adding that he was determined to ‘curb the disfiguring impact of excessive costs.’ He added: ‘I intend to bring this judgment to the attention of the president [of the high court’s family division] with a view to him raising this pressing issue as a matter of urgency with the family procedure rules committee.’

More than a decade later, Mostyn admits those calls fell on deaf ears.

Counting the costs

‘When I spoke about this more than 10 years ago I feared that nothing would come of it,’ he tells Spear’s. ‘That has sadly come to pass. The only change that has taken place as far as I can see is that fees have since gone up exponentially.’

In that now famous case, the husband, a market gardener then aged 54, and the wife, aged 44, separated after having been married for 15 years. At the time the couple – known only as J and J – had two children of 17 and 16. The costs in their case started to escalate when they were allowed by a district judge to each hire their own experts to value the husband’s business. Many experts later, total costs grew to £920,000. But this figure pales in comparison with some of the cases that go before the courts.

Mostyn says: ‘Again and again, judges come out and say something must be done, and then, as expected, nothing happens. Greed, it seems, has taken over. Justice becomes meaningless if people can’t afford it.’

So what is the solution? According to the former judge, fixed fees might be the answer. ‘They can help put a lid on soaring costs,’ he says.

Explore the 2025 Spear’s Family Law Indices:

- The best family lawyers for high-net-worth clients

- The best family law barristers for high-net-worth clients

- The best litigation funding providers

Fixed fees ‘motivate staff’

Step forward Georgina Hamblin, founder of Hamblin Family Law, the first firm of solicitors in its field to offer fixed fees across the board. Hamblin, who spent 10 years at divorce specialist Vardags, well known for its high fees, set up her firm in 2023 because she said she wanted to ‘do something about’ rising costs, as well as opt for a pricing model that would get her new firm noticed.

‘Fixed pricing gives clients complete certainty on their costs up to a particular point in time,’ says Hamblin. ‘It also motivates staff to be as efficient as possible with their client’s money. The age-old hourly rate does the opposite. It rewards those who leave clocks running and over-litigate their cases, and leaves staff living under the fear of their hourly rate targets.’

So far, her model has proven popular. Having started as a one-woman band at launch, the firm now employs 11 people and has worked with more than 100 clients.

‘Given I was going it alone, I knew that charging fixed fees would be a way of standing out from the crowd,’ says Hamblin. ‘Fixed fees have allowed me to grow the business very rapidly.’ The hourly rate, she adds, is ‘clearly becoming completely uneconomical for clients’.

Do fixed fees mean cheaper fees?

Not everyone agrees, however. Hamblin’s former employer, Vardags, is among those to take issue with her hypothesis. The firm, which was launched by Ayesha Vardag in 2005, has become one of the go-to practices for the very rich.

The founder, for example, who charges £1,200 per hour for her services, worked for beauty queen Pauline Chai when, in 2017, she was awarded a £64 million settlement in her split from ex-husband Khoo Kay Peng, the Malaysian-Chinese businessman in charge of a multimillion-pound business empire that included high street chain Laura Ashley. The payout followed a ‘titanic’ legal battle in which the judge noted: ‘The actual resolution of the finances of this couple, who have more money between them than they could spend in their lifetimes, has unfortunately taken a second seat.’

Vardags managing partner Emma Gill tells Spear’s: ‘You have to remember that fixed fees don’t mean cheaper fees – they only mean that there is more certainty over the amount paid. A lot of people seem to misunderstand that, which could be a big mistake and come at their great expense.

‘Proportionality is the watchword. Sometimes the costs may be high but the money at stake is far, far higher. The bigger public menace in my view are law firms doing work that they are not capable of doing.’

[See also: The best family lawyers in the UK]

Driving the divorce bill

But it is not just solicitors who are accused of leaving the clocks running, as Hamblin puts it. Fingers have also been pointed at barristers for encouraging the spike in costs. It was difficult to get a barrister to discuss fees on the record for this article, but one former family advocate told Spear’s that solicitors, rather than barristers, were to blame: ‘My experience is that solicitors have made hay and barristers have not. In fact, the rates for barristers are still almost the same as when I stopped working more than 10 years ago.’

Another barrister, who still practises, adds: ‘Like any sector where highly specialised knowledge and experience is required, there will be fewer people in a position to deliver that knowledge and experience. It therefore becomes more about providing the best value to a client than simply the cost.’

Mostyn, however, is not so sure. He has little doubt the system is set up for cases to be dragged on and for costs to mount up. Value, he believes, has become hard to find.

He references another case he presided over just before he retired in 2023, in which he described the charges as ‘apocalyptic’. In that case, Lazaros Xanthopoulos, a Greek-born Russia resident, who described himself as a homemaker, and his former wife, Alla Rakshina, who was described in court as the 75th richest woman in Russia with interests worth more than £300 million, fought over two London properties worth £5 million each and a sum of £11 million in a Coutts bank account. The legal costs, meanwhile, were on track to hit £8 million in order to settle the dispute.

[See also: A guide to The Spear’s 500: Everything you need to know]

The case for capping costs

Mostyn said in his judgment: ‘It was difficult to know what to say or do when confronted with such extraordinary, self-harming conduct […] Figures like this are hard to accept even in a conflict between the über-rich […] In my opinion, the Lord Chancellor should consider whether statutory measures could be introduced, which limit the scale and rate of costs run up in these cases.’ Again, those pleas went unheard, with costs continuing to swell.

For Vardags’ Gill, a lack of what you might call ‘market interference’ is welcome. In her view, clients should be free to spend what they like on the provider of their choice: ‘You get what you pay for. Some of us shop at M&S and some of us shop at Harrods. We live in a liberal democracy where people can spend their money as they wish.’