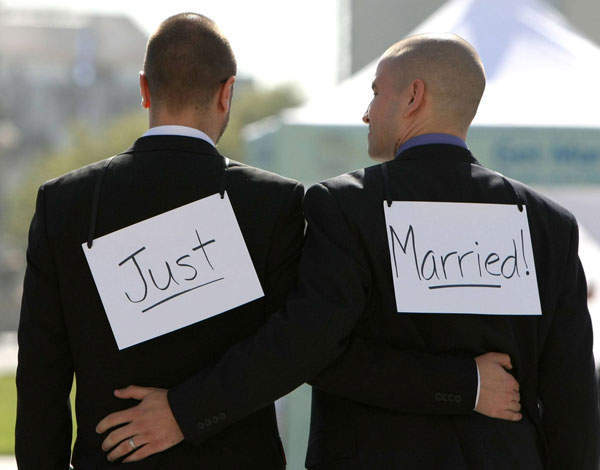

The Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act 2013 came into force on 13 March 2014 and same-sex marriage will become legal in England and Wales on 29 March. Existing non-UK marriages of same-sex couples will also be legally recognised from this date.

One of the fundamental features of the new legislation is the principle of ‘equivalence’. This means:

> References to marriage and related terms in existing legislation, however expressed, will be read to include same-sex marriages; and

> References to marriage and related terms in new legislation will be read in a specified way. For example, the term ‘husband’ will include a man married to another man, but not a woman married to another woman (thereby preserving the gender specific meanings of terms such as husband and wife).

Read more on marriage from Spear’s

Importantly, the equivalence provision does not alter the effect of any private (ie non-legislative) legal instruments made before 13 March 2014, including wills and trusts, and the Act itself does not contain any rules on how to interpret these private legal instruments made on or after 13 March 2014.

The meaning of these terms in wills and trusts will, therefore, be a matter of the construction of each document. In the absence of anything to the contrary, the natural reading of a will or trust made before 13 March 2014 will therefore be that references to spouses do not include same-sex spouses, ie your will may not automatically leave what you want to your same-sex spouse.

Read more on the law from Spear’s

On the other hand, the natural reading of an instrument made on or after 13 March will normally be that references to spouses include same-sex spouses. However, the Act does not impose or require this interpretation, which gives flexibility for those who want it, but may inadvertently create uncertainty.

Further scope for confusion is caused by the provisions of the Act which will enable couples already in civil partnerships to convert to marriage (this is not yet possible). We know that the effect of a conversion will be that the civil partnership will end and the couple will be treated as having been married since the date the civil partnership was formed.

We assume – but it is unclear from the Act – that this will not trigger the automatic revocation of a will (which happens when a testator enters into a civil partnership or marriage) and/or the presumption that a spouse or civil partner has died before the testator (which happens when a marriage or civil partnership is dissolved).

It is of course hoped that these potential wrinkles will be ironed out in time. For now, however, it is more important than ever to ensure that the wishes of a person making a will or trust are stated clearly, so that their intentions and preferences relating to the meaning of terms such as ‘spouses’ and ‘partners’ cannot be misunderstood.

Lydia Essa is a Senior Associate at boutique private wealth law firm Maurice Turnor Gardner LLP