The recent revelation that the dating website OKCupid ‘experimented’ on its users by purposefully making statistically ‘bad’ matches look ‘good’, and omitting key user profile information when setting up matches, appears to have come as something of a shock to some of its users.

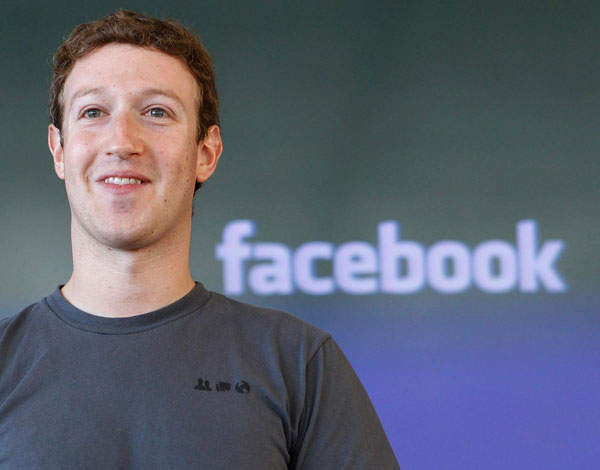

In another recent online experiment, Facebook revealed that it had attempted to manipulate users’ emotions by altering news feeds so that they contained either predominantly positive or negative emotional content, and then assessing how the users’ subsequent posts were impacted by the trend.

Are users putting too much trust in service providers such as Facebook and OKCupid in relation to how their data is used? To what extent does the law protect the users from these kinds of experiments?

When experiments involve any use of personal data such as users’ names or other information relating to them, UK data protection law requires that the controller of the experiment obtains the users’ consent before the experiment starts. The key exception to this is where such usage is necessary for certain purposes, which are unlikely to be the case in such experiments.

Most service providers seek to obtain consent by including appropriate language in a privacy policy or privacy notice which is made accessible when the relevant data is collected. When an individual user accepts such a privacy policy, either by a positive action such as ‘click to accept’ or by continuing to use the service when the privacy policy has been clearly presented to the user, they are consenting to use of their personal data in the manner set out in the privacy policy.

In addition, more stringent rules apply to use of particularly sensitive personal data such as ethnic background and sexual orientation. Any use of this type of data needs express ‘opt-in’ consent.

If, prior to signing up to use the services, prospective users of Facebook and OKCupid had read through the respective privacy policies and seen wording such as: ‘We will use your data to conduct experiments on you’ or ‘We will use your data to attempt to manipulate your emotional state’, would they have been likely to sign up? Maybe not. It is unlikely that any service provider would use such wording.

Instead, something as broad as ‘We will use your data for research purposes’ might be considered, although it is worth noting that the more unusual the proposed research, the more information users could expect to receive in relation to the experiment prior to giving their consent. Essentially users need enough information to be able to make a choice about whether the proposed use is acceptable to them in order for their consent to be effective.

The Information Commissioner’s Office, the independent authority responsible for data privacy for individuals in the UK, has the power to issue fines of up to £500,000 for serious breaches of data protection law. The size of the fine will depend on the level of seriousness of the breach. It’s unlikely that experiments along the lines above would attract fines towards the higher end of the range, but there is a bigger issue at hand: the issue of trust.

In gaining users’ broad consent by way of a privacy policy service providers might be able to show compliance with their strict legal obligations, but where users feel their data has been misused this is unlikely to be much comfort.

The reality is that few users (even lawyers) thoroughly review privacy policies and terms and conditions before clicking ‘I accept’ or ‘I agree’. There is an element of trust on the part of users that service providers will not use their data in a manner which would be unusual or weird.

Perhaps some users aren’t surprised, or bothered, if their personal data is used in such experiments – and maybe we’ll all become increasingly less concerned about it in the future – but it’s clear that a significant number of users were surprised by these experiments and the way in which their data was used. They didn’t expect it and didn’t like it.

Many users expect any unusual uses of their personal data to be brought to their attention in a more prominent way than merely including a general notice in a service provider’s privacy policy. Even if the relevant privacy policy had contained language clearly explaining the experiment, they may still have been upset.

If a service provider is considering the use of a user’s personal data in a new or unusual way, the best policy is to obtain clear express consent first.

So what about the Facebook and OKCupid experiments? Would there have been any issue if the service providers had only conducted the experiments on users who had expressly agreed to take part? Facebook and OKCupid may argue that this would have produced less genuine results, but this is perhaps a small price to pay for the retention of their users’ trust. You never know until you ask.

If you are a business with concerns over the handling of your data, or would like assistance in relation to your privacy policy or CRM activities, contact Dan Tozer, head of commercial technology at Harbottle & Lewis