In 1973 the most powerful restaurant critic of the day, one Egon Ronay, made a trip to Bray. There, in that pretty village by the Thames, he visited an old pub, refurbished and graduated to restaurant status. It was the Waterside Inn, then co-owned by two French brothers, Michel and Albert Roux.

The brothers had already created a stir with their London openings. There was Le Gavroche, which had been going for some five years, as well as Le Poulbot (a restaurant in Cheapside) and their Old Bailey establishment, Brasserie Benoit. But now the brothers were casting their net wider, looking to create a restaurant that could service the wealthy residents who owned houses around the Thames, in towns like Marlow and Henley.

The place had been open for about a year before Ronay’s visit. Weekends were busy, but the weekdays were a struggle, with just ten to twenty covers booked for lunch or dinner. The chef was Pierre Koffman, his menu was written in French and it was classic French fare: soups and pâtés, cassoulets and grilled fish for main course with the likes of tarte au citron and sorbet for dessert. Ronay’s review appeared in the pages of the Daily Telegraph. And he made a bold pronouncement. ‘One day the Waterside Inn will be the best restaurant in Britain,’ wrote the critic who could make or break an establishment.

Now, over 40 years later, the Waterside Inn is certainly one of the most famous restaurants in Britain. As to whether it’s the best, its fans point out that it has just achieved something no other UK restaurant has managed: it has now held three Michelin stars for 30 years. That third star came in January 1985, with a telephone call to Michel while he was on holiday in Australia.

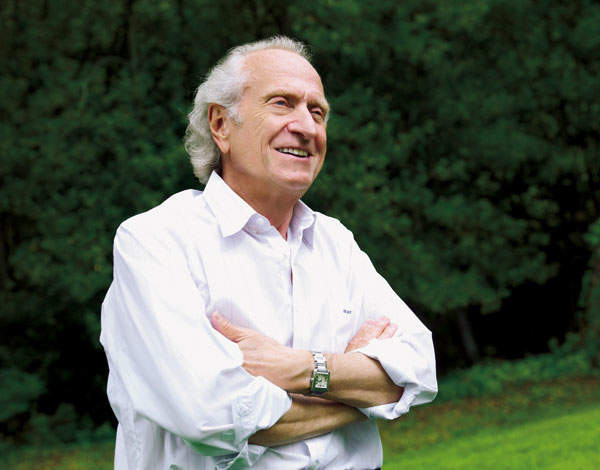

Today Michel Roux Snr still presides over the restaurant, although he lives in Switzerland, and while his son Alain is chef-patron, his head chef is a Belgian, Fabrice Uhryn. Service, meanwhile, is run by Diego Masciaga, viewed by many in the industry as one of the finest maître d’s in the world.

Michel and Albert split the business in 1986, with Albert taking Le Gavroche (now the domain of his son Michel Roux Jnr) and Michel the Waterside Inn. But while the Waterside is famous for its elaborate classic French cuisine, it is the simple food of his mother that stirs his memory.

‘My mother always cooked from scratch,’ he says, now a suave and nimble 74, utterly charming, always joking and never failing to compliment any woman who comes within a few feet. ‘I was always fascinated by the smells that came from the kitchen, the aromas from the different stages of cooking — from peeling to actual cooking — being like clues in a crossword.

‘But that food was always humble. I was born during the war so there was little choice. It was repetitive, but I was always interested. From the age of four or five I wanted to help my mother cook. I loved to see how mashed potato went through the moulis. I would pull her skirt and say, “I want to do it.”

‘I used to love the noise that mussels would make as you cleaned them, their shells knocking against each other, that rattle. If I heard that noise, I was in the kitchen like a shot. I learnt to clean them, then how to braise them and drain them. My mother would add some cheap wine (Algerian), then shallots, thyme, a bay leaf. I wasn’t strong enough to shake the pot, so I would climb on a stool and stir them. I would lift the lid and get that smell. Oh the smell…’

Michel’s vivid recollections continue as he explains how he would burn his finger checking if the mussels were cooked before his mother took them off the heat and covered them with a hot towel to rest. Then she would make a sauce with the juice, a little milk, flour and some precious butter.

His descriptions of this and other simple dishes of his childhood leaves one swooning at the simple yet romantic picture, not to mention itching to get home, buying some mussels on the way, and attempt to re-create this dish.

He talks of how they ate slices of marinated herring with boiled potatoes and a raw onion and parsley vinaigrette, little plum tarts — the dough made with pork fat — slow-cooked belly of pig, rabbit with mustard, a splash of wine and mushrooms picked from the fields. This frugal childhood instilled in him a love of simple but good ingredients and a pragmatic approach to food.

‘If I go to a market today I never go with a list. I look for the best ingredients,’ he says. ‘To start with, the best ingredient is actually more important than cooking. And you get that knowledge by experience. If I’m choosing, for example, a cauliflower, I want to see green leaves around the base, I’ll touch the bottom to test for freshness. The cauliflower will talk to me and look as fresh as a flower. I touch, look and smell wherever I am, market or supermarket.’

As for those Michelin stars, he muses on the pressures of retaining the accolade. ‘The first year was the toughest. Each year you then wonder… After ten years I thought this can’t go on for ever. I remember seeing my brother lose his third star for Le Gavroche and how he reacted. I thought some day it could happen to me. Nothing in life is for ever. After all, you only need to serve one average meal to a Michelin inspector and you’ve had it.’

So far Michelin appears to have no appetite to delete those stars, however. Meanwhile, Michel’s appetite is for establishments with the Michelin Bib Gourmand. ‘That’s what I look for, especially if I’m travelling. But if I don’t have a guide book to hand, I go to the chemist. They are like doctors — they always know what will make you sick or well. So I ask who the owner is and say I have a personal matter to discuss. Then I get their recommendation. I’ve never been disappointed.’

These days Michel consults on a number of restaurants around the world and has a few sage words of advice for budding restaurateurs: ‘Success can go to your head and can be more difficult to handle than failure.’ He also has a word for cooks whose food is too complicated and doesn’t adhere to the simple truths he learnt as a child: ‘Always let the ingredients talk to you. Not enough chefs today can actually taste; they haven’t got a palate. They use too many sauces, too many herbs and value the visual over flavour. It’s like a woman: you can meet a 30-year-old and she’s very beautiful, but too much mascara, or too much perfume and she kills it. A dish can look good, but it’s nothing if it doesn’t taste bloody good.’

At which point Michel Roux Snr is off, to the Far East. ‘What I’m doing in Vietnam now is what I did in the UK 40 years ago,’ he says. And given that he transformed the way we ate, they’d better look out.