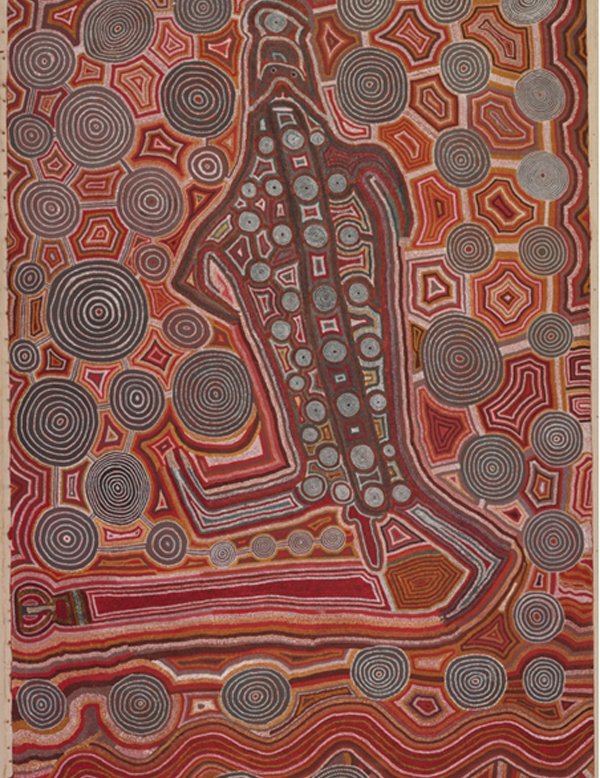

Above: ‘Kungkarangkalpa’; Kunmanara Hogan, Tjaruwa Woods, Yarangka Thomas, Estelle Hogan, Ngalpingka Simms and Myrtle Pennington; 2013; Acrylic on canvas. © The artists, courtesy Spinifex Arts Project.

‘Why are the b m [black men] angry?’ – ‘Because the white men are settled here.’ So reads a conversation between Royal Marine officer William Dawes and Patyegarang, an indigenous Australian. The transcript is one of a number of conversations in Dawes’ notebook that detail his attempts to understand the language of the land to which he had been sent.

Language is just one parallel explored by the British Museum’s exhibition. It is a display that is objective and intelligent enough to recognise the gulfs in understanding between Europe and Australia, not as something to be vainly bridged by an apologist, as sentimental history, but as an indelible and unmovable part of an indigenous narrative that began 50,000 years before Abel Tasman’s ‘discovery’. That is something not done through overly complex interpretations but a considered approach to a ‘big country, big story’ that lays out the indigenous heritage before showing the cultural blistering caused by Cook’s claiming of the continent in 1770.

From the start visitors are familiarised with ‘the dreamings’ and their importance in indigenous culture – the blurring of time, space and consciousness being integral to their understanding of the world and their place within it. This is shown inside the abstract canvasses such as those by the Spinifex people, colourful layers scatter-gunned with looming dark holes. It’s an enticing aesthetic, very deliberately made with story and place in mind.

The curation refers to the importance of place – not only the physicality in the artists being ‘of’ the land, but within legend, experience and memory. They are atlases of thought and in reaching out to a remembered, rather than a catalogued, history they give a sense of place as much about connection as presence.

Physically placing respective nations is more challenging: a large map on the wall shows the different groups of peoples native to Australia. It resembles camouflage in its overlapping, intricate colour-coding and it sits beside a timeline that jumps tens of millennia at a time: it is a history poorly served by charts; it has its own considerable interior, a hinterland hidden behind, and subject to memory – dreamed in itself but no less present.

That is not something easily conveyed in a London museum but this exhibition deserves credit for allowing our understanding to be signposted by artefacts while not being parsimonious when curation must fill in context.

Shield believed to have been collected during Captain Cook’s visit to Botany Bay, 1770. Mangrove bark © The Trustees of the British Museum

Bark blankets, spears throwers, masks, baskets and jewellery all belie a domestic existence shaped by desert living. The art is heady with carvings and paintings showing creation narratives fizzing with serpents, rocks, crocodile-men and fire. More romantic curiosities are piqued by boomerangs designed to mimic hawks, two metre long crocodile masks, coral fire guardians and medieval looking fish traps ‘similar to ones used on land to trap wallabies’.

Then, having established the delicate cultural parameters, the narrative suffers an earthquake – Moorehead’s ‘Fatal Impact’. It is a metaphorical and physical dislocation as the exhibition’s latter half incorporates the dialogue of misunderstanding between a system used to interring, rationalising and moulding the world and a society consciously disinterested in totalising.

The testaments to exploitation and theft the indigenous Australians suffered are interspersed with contemporary pieces such as Michael Cook’s image of a black 18th century Royal Marine and Vincent Namatjira’s painting of James Cook holding his declaration claiming Australia for the crown – flowing from his uniform in a not un-phallic fashion.

James Cook – with the Declaration; Vincent Namatjira, (b.1983), South Australia, 2014, Acrylic on canvas © Vincent Namatjira

Poignantly it is the hypocrisy of British law that is shown up. One example is the arbitrary unilateral contracts, such as the Batman declaration, that looked to remove indigenous Australians from land they had inhabited for millennia. To avoid such perversions of the legal system the crown sought to claim all Australian land before apportioning it to claimants, solving a puzzle with an enigma for those who already lived there.

Land lies at the heart of the matter for both sides. One can almost see the chasms of ignorance yawning from Cook’s flagpole; he claimed an entire continent on his assumption of Terra Nullius, the concept of no one’s land. It was the caveat that swallowed the future of the aborigines. Perhaps if the British had had the mindfulness of place represented by ‘the dreamings’, rather than a hole in their own map marked ‘Nondum Cognita’ (not yet known) and the misplaced prerogative of a painted cloth on a stick, they would have avoided their mistakes.

But Europeans dream differently. The universal narrative of the British Empire is exploitation – whether numbed into the subconscious by legal reasoning or not is academic. The bloodied shields and weapons on display show what happens when agents of law choose to forget themselves and reach for violence and the blinkers of Orientalism.

Thankfully such institutionalised viewpoints are absent in the curation. Given the history of the establishment this exhibition sits in, that is quiet but welcome recognition and marks this as a thoroughly modern window on this story. That story continues: one of the last exhibits is the unsuccessful request from Torres Strait Islanders requesting the return of their ancestors’ remains from the British Museum, it is dated 2011.

‘Yumari’, Uta Uta Tjangala (c. 1926-1990), Pintupi people, Papunya, Northern Territory, 1981, Acrylic on canvas. National Museum of Australia

A closing film details the struggle for indigenous rights in modern Australia and how a fusion is being gingerly created between these two narratives. Political reconciliation needs good history. In showing how the most complex of narratives are constructed, and how they are understood through objectivity, chronology and culture this exhibition is a wonderful example of that.

However, the absence of sentiment does not inhibit our own emotions. It is also a powerfully raw look at the wounds left on one culture that has been forced to endure more than another. For both these things it should be applauded.

Indigenous Australia, Enduring Civilization at the British Museum is on until 2 August 2015