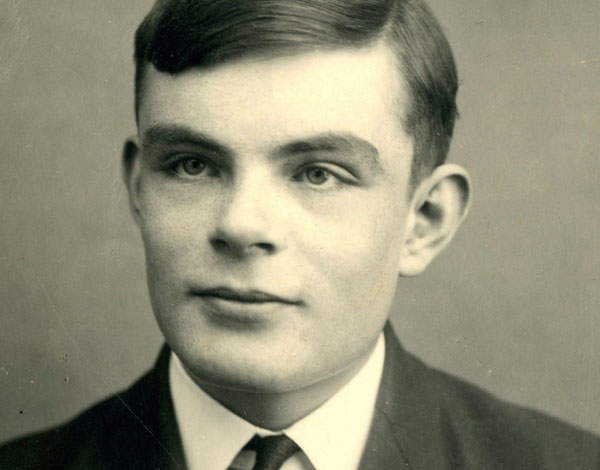

Just before Christmas, Queen Elizabeth granted a posthumous pardon to Alan Turing. By common consent, Mr Turing was a remarkable man. He has been called the ‘father of modern computing’ and his genius in breaking the Enigma code of the German forces had a major part in shortening the length of the Second World War.

Seven years after the end of the war, he was convicted of gross indecency with another man. Homosexuality was, at that time, illegal. After his sentence of chemical castration, he suffered bouts of severe depression and committed suicide in 1954.

The pardon which has been granted is under the Royal Prerogative of Mercy, which is entirely at the discretion of the monarch. It allows the monarch to pardon an offence or change or withdraw the sentence. We know that, in the Turing case, it was granted after the justice secretary had asked for it to be exercised.

Read more on the law from Spear’s

It also cut short the need for an Act of Parliament which had started its progress by being passed in the House of Lords during 2013 and was due to have been considered by the House of Commons this year. There was every expectation that it would have passed its stages there successfully.

By its very nature, the Prerogative of Mercy cannot be limited, but my concern here is not about our guilt over what happened to Turing, rather about the attempt to rewrite history. There are other examples of the Prerogative being exercised, indeed posthumously, but often they have been cases where there was a real doubt about whether the person who had been executed had really committed the offence.

A particular example was the notorious case of Derek Bentley, who was executed in 1953 for aiding and abetting the murder of a police officer. The fatal shot was fired by a sixteen-year old, Christopher Craig, who could not be executed because of his age.

Bentley, who was nineteen at the time and had a history of personality and mental health problems, was convicted on the grounds that he was said to have used the words to Craig ‘Let him have it’ before the officer was shot.

It took 45 years for a full pardon to be granted, including a case before the Court of Appeal about whether an earlier refusal by the home secretary to recommend a pardon could be judicially reviewed. But here, in essence, the final pardon was granted on the basis that, on the evidence, Bentley should not have been convicted of murder.

Like it or not

In the Turing case, the pardon was proposed not on the grounds that the evidence did not support a conviction, but that the law making homosexuality illegal should not have been in existence. But I am sorry — that was the law at that time, like it or not.

If Turing is pardoned, surely there are thousands of other cases convicted under laws that, in our eyes, are barbaric, which could, and probably should, similarly be so reviewed. What about those sentenced to death for what we would consider petty offences, such as sheep stealing? They are in no different a situation.

And if Turing benefits, why should any other person convicted of that same offence not be treated similarly? The status or stature of a person convicted of an offence has no relevance to whether or not he committed the crime of which he is accused. We are fashioning for ourselves a moral maze if we try to rewrite history.

The counter-phenomenon, of prosecuting historical crimes, is one we see today too. At the moment, there are a number of cases where media personalities, and of course I am thinking of Jimmy Savile, are being accused of abusing a range of young and impressionable persons. A number of the accused have been convicted and others are facing trials in the forthcoming months.

Where does this zeal come from? It is surely exacerbated by a collective sense of guilt at contemporary inaction, thus betraying the victims. At least in prosecuting these cases from a generation ago the victims may today feel that society understands their hurt.

O tempora! O mores!

But concerning Turing, my worry is that the law even those few years ago (for 65 years in the history of English law is but a short span) was very different and society was very different. The current law represents what we want it to be for our society in 2014, and that is why we fiddle with it so frequently.

However, given the amount of trouble we have with making the law the way we want it to be, does it make sense to try to pretend that the law was the same a generation ago, when it simply wasn’t? Who do we benefit by reopening cases and judging past activity by current standards? The damage has, sadly, been done, and the reason the law changes is because we move to an acceptance that we should do better.