There’s nothing an emerging markets analyst loves more than a good acronym. First it was the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India and China), the group of fast-growing major economies identified by Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neill as a source of returns during the depths of the financial crisis.

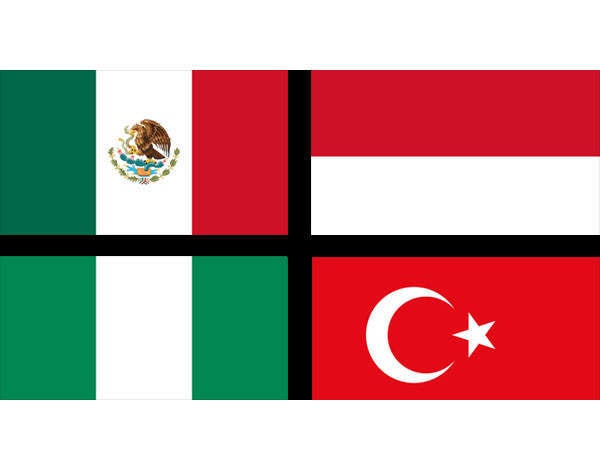

More recently O’Neill has been extolling the virtues of the MINTs (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey), although this time he had fund manager Fidelity to thank for inventing the term.

BRICs and MINTs are just a spoonful of an alphabet soup deployed to describe promising parts of the world to send your capital. Further much-vaunted alternatives include the CIVETS (Colombia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Egypt, Turkey and South Africa) or another O’Neill invention, the Next-11 of Bangladesh, Egypt, Iran, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, South Korea, Turkey and Vietnam. BBVA Bank came up with the EAGLEs, Emerging And Growth Leading Economies, yet another long list of potential ‘next big things’.

Read more on emerging markets from Spear’s

The attractiveness of these loosely grouped nations has been enhanced by the money-printing that Western central bankers have adopted to mitigate effects of the worst financial crisis in living memory. As money sloshed into the major economies, investors sent it across borders and into unfamiliar territories in search of better returns, stoking their growth still further.

But the spectre of ‘tapering’ — the beginning of the end of America’s great stimulus experiment — has cooled off investor excitement somewhat. (See page 40.) The immediate reaction to the onset of tapering has been relatively muted, with much of the damage already done last year by investors anticipating its arrival, but there is turbulence ahead, with many Western investors likely to repatriate their cash in readiness for interest rates at home moving off record lows.

Capital market flows to emerging economies could fall by as much as 80 per cent post-taper, the World Bank has said. Indeed, IMF chief Christine Lagarde spoke of the potential for ‘rough waters’ in emerging markets, urging vigilance against rising debt and asset bubbles. The benchmark MSCI Emerging Market Index dropped by nearly 4 per cent in five trading days recently, and some economies are particularly vulnerable.

The economic coming of age seen in sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, is in serious danger. It has been a common dinner party fact of the past few years that seven of the fastest growing economies are in Africa. For many of these countries, where capital investment is a huge slice of GDP, further tapering could hurt badly.

There is cause for concern around countries with ‘large current account deficits and heavy burdens of external debt’, according to Capital Economics analyst Neil Shearing, who adds: ‘We are especially concerned about Turkey, South Africa and India.’

Those with abundant natural resources cannot turn to the commodity price environment for succour because metals are still in the doldrums, while some pundits see oil falling to $80 per barrel this year.

Turkish wrestling

For investors, handy groupings such as the MINTs may be of little help in times of economic flux, since it would not be wise, for instance, to assume that Mexico and Turkey will perform in tandem. The latter is closely tied to the prospects of its export customers in Europe.

It has also taken great advantage of US stimulus to borrow in order to fund spending, but as the Fed withdraws the punchbowl from the party, the government’s attitude to spending is likely to become rather more sober. Turkish politics is also increasingly tumultuous, although this need not necessarily be a bar to successful investment.

Mexico’s fundamentals are very different. It may be wrestling with the pernicious influence of the illicit drugs trade, but the legitimate economy can cling on to US coat-tails as its recovery gets under way, manufacturing cheap goods for increasingly confident households. Investors should look to characteristics such as these rather than relying on a convenient collection of letters.

Liquid assets

The stewards of emerging economies and the businesses who trade with them will need to think on their feet. The World Bank has pointed out that financial crises in the developing world tend to hit when a long period of capital inflows is followed by a sudden withdrawal of funding, but with major change always comes major opportunity and as the glacier of cheap money melts away, there will be gems left gleaming in the moraine.

Stocks listed in emerging markets but reliant on US and European growth, for instance, look a good bet, as do shares in companies that tend to do well when their domestic currency weakens, such as those whose cost base is in domestic money but who count their revenues in stronger currencies.

And the taper effect may yet prove overblown: if US interest rates rise only gradually, equity market volatility in emerging markets could prove smoother than feared. Bond investors will be able to locate steady income from countries such as Mexico, where sovereign debt returns 4 per cent — a healthy rate for a relatively sturdy economy when set against 2.8 per cent on US Treasuries.

Few forecasters expect growth in the developed world to return to the rates seen in the pre-crash years — but what has become clear is that emerging markets are no longer a default alternative.