The era of Netflix and online gaming has breathed new life into the works of some long-dead authors – but who reaps the financial rewards from this renaissance? The answer to who benefits from the intellectual property gold might depend on your lawyers, says Sam Leith

Towards the end of last year, Netflix announced that it had acquired the Roald Dahl Story Company – and that it had allocated a production budget of a cool billion dollars to create a set of stories in the ‘Roald Dahl Universe’. Not a bad score for the back catalogue of a writer who has been dead for more than 30 years – and some of whose unsavoury personal pronouncements put him in line for ‘cancellation’ not so long ago. It was a development that will have been watched with avid interest by the families and estates of writers whose works remain in copyright.

Let us say, for the sake of argument, that you, reader, are sitting Smaug-like on a pile of intellectual property gold. Perhaps your grandfather wrote a series of successful science-fiction novels, or your great-grandmother created a series of children’s books about jazz-dancing chinchillas which are still selling well in backlist. You are managing an author’s estate, in other words, and reprint royalties are trickling in but nobody’s getting rich – or not as rich as they’d like – from them. You look at Beatrix Potter’s rebirth in the blockbusting Peter Rabbit movies, or at the Roald Dahl deal, and you think: I’d like me some of that.

How do you go about it? What are the opportunities and the pitfalls? In the digital age, when streaming services are crying out for properties on which they can build franchises, the opportunities have seldom been greater. The disposable pulp medium of the comic book has begotten, in the Marvel and DC universes, the biggest entertainment franchise of our times. Cross-platform synergies – from merchandise to pick-up video games to Hollywood blockbusters – can turn old stories into golden geese. That’s the good news.

The bad news is that this pile of gold on which you are sitting is trickling away. An estate, like the leasehold on a piece of bricks-and-mortar property, dwindles in value as time goes on. The closer you get to the point at which the work passes out of copyright – in the UK, that’s usually 70 years after the author’s death – the less value there is in it. A beneficiary of one of the bigger literary estates to have been sold recently told me: ‘The key thing to remember with all of this IP is that if it’s based on artistic work, it has a natural expiry date. Every day you go without resolving that, the value, obviously, decreases.’ The best time to sell is yesterday, in other words, and the second best time is now.

‘The worst possible mistake you can make is hanging on to it really doggedly and not actually pursuing any sort of development or opportunities work,’ he says. ‘So obviously, if you hold on to quite a valuable IP, and you don’t actually let anyone do anything with it, or you maintain complete editorial and artistic control, no one’s going to want to touch that with a bargepole.’

He adds that there’s another route. What has been accepted entrepreneurial practice in the music world – think, say, Michael Jackson buying publishing rights to Beatles songs – is starting to be seen as a literary possibility as well: you could leverage your rights in one set of copyrights to buy others, and turn your holding into an intellectual property company.

But if you are going to sell up rather than turn the estate into an ongoing business, it will pay to get it into better shape to sell. One of the key things to do is to set about re-acquiring rights: ‘A lot of authors in the 20th century gave away rights very easily and very cheaply and very badly.’

You might think, too, about the emergent cross-media ‘extended universe’ model, which means the most valuable properties are no longer stories so much as characters and worlds. Derivative works – new tweaks to old characters (Pooh with Disney’s red pullover, say), or new stories set in existing fictional mises-en-scène – will generate fresh intellectual rights that can extend the life of a property indefinitely.

Stian Westlake, co-author of the new book Restarting the Future: How to Fix the Intangible Economy, says there are three main things to consider if you’re in control of an estate: ‘The first is your legal rights over the creative property. The second thing is what I would call synergies: how you can connect these creative works to other things to increase their value. And then the third thing is the emotional side, the fact that ultimately these are expressive works and you have to think about the social and emotional value of this to you as well as monetising it.’

In legal terms, says Westlake, it’s a question of securing and shoring up your rights to the intellectual property. He continues: ‘The second thing is the kind of synergies: these assets are especially valuable when you bring them together with the right other intellectual property assets. The classic examples are things like Harry Potter or the Peter Jackson Lord of the Rings movies. It created something that was, you know, massively more valuable than the underlying royalties from the books.’ (Conversely, getting the synergies wrong can have the opposite effect. Alex Garland was able to pick up the rights to Judge Dredd for very little money because Sylvester Stallone’s dud movie had effectively torpedoed the value of the character.)

Finally, there’s the question of your emotional relationship to the material. This is a matter of personal choice. Are you determined to control the use of the material to honour what you suppose to be grandpa’s wishes – or let the likes of Amazon Prime stuff your mouth with gold in exchange for doing what it wants with the character?

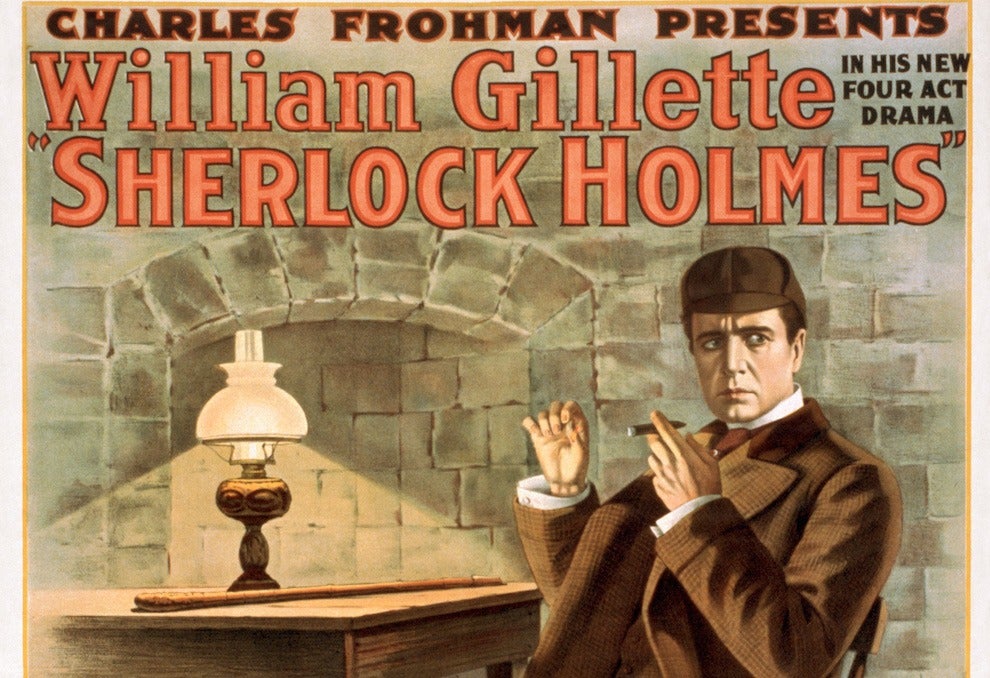

These issues, both creatively and legally, can be complicated. Witness the recent punch-up between the Conan Doyle Estate and Netflix. The former argued that in the 2020 film Enola Holmes, Netflix had portrayed a softer and more human version of the great detective; the estate’s contention was that cuddly Sherlock emerged only in the stories Conan Doyle wrote in the 1920s, so those character traits remained in copyright in the US even if the character didn’t. At this point, you might be thinking, copyright lawyers will be forced to defer to literary critics. As Netflix’s lawyers argued successfully at the time, ‘copyright law does not allow the ownership of generic concepts like warmth, kindness, empathy, or respect’.

Since derivative works can create a fresh start for intellectual property, there’s further room for manoeuvre. Winnie-the-Pooh, for instance, may now be out of copyright – but Disney has effectively put him back into copyright by creating new stories and a trademarkable visual image (that red pullover) which has in some respects supplanted AA Milne (and EH Shepard) in the public mind. While the literary estate you’re handling may be a set of stories, the video game company, streaming service or T-shirt manufacturer to whom you’re selling rights may well be interested primarily in making new (and freshly copyright) stories and images of the characters and the world of those books. If you want pointers on IP in general, it barely needs saying, Disney is the one to take lessons from. Even those without much interest in the subject will be aware of the so-called Mickey Mouse clause – the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, when Disney successfully lobbied to have copyright in corporate works extended to 95 years after first publication. That means Mickey now comes out of copyright, theoretically, in 2024 (the mouse’s first appearance, in Steamboat Willie, was 1928).

Of course, as drawn now, Mickey doesn’t look anything like his first incarnation; and you can be sure that Disney will also assert trademark rights – which can be seen as granting a perpetual copyright – against anyone foolish enough to decide Mickey is now anyone’s property. To take another example, Edgar Rice Burroughs may be mostly out of copyright, but ‘Tarzan’ is still a trademark. So if in doubt, engage a specialist intellectual property lawyer. They are worth their hire.

There’s likely to be a trade-off, in all cases, between realising value and retaining control. A cautionary note is, perhaps, sounded by the Tolkien estate, which for many years was controlled by the writer’s son Christopher. He did what he could to eke out royalties from the printed work – publishing any number of posthumous partial works and elvish barrel-scrapings – but he didn’t realise the sort of money that he might have, given the titanic popularity and influence of the stories, by selling the rights to Middle Earth as a package. Not, I imagine, that the Tolkien estate will be complaining: in a better-late-than-never move, the TV rights to Tolkien’s works were sold to Amazon for $250 million in 2017.

Even estates that aren’t going to yield that sort of super-jackpot are worth managing shrewdly. Lisa Dowdeswell, who manages authors’ estates for the Society of Authors, says that in the first place there’s much that can be done, especially in the age of print-on-demand, to keep works in print. What some might not think of, she says, is that ‘foreign rights tend to be more lucrative, actually, than the original UK language rights, especially in older works – because they’re shorter licences and they pay advances’.

The Society has managed the estates of writers such as Virginia Woolf and George Bernard Shaw – and as she’s keen to point out, you don’t need to be an author to join the SoA and enjoy its advice and protection. Of course, keeping a book in print not only creates royalties, it also helps maintain a profile and a public to dangle before the noses of film and television companies. She confirms that intellectual property companies, not to mention streaming services and film studios, are constantly on the scout for rights that might be up for grabs.

The Jazz Chinchilla Extended Universe? Stranger things have happened.