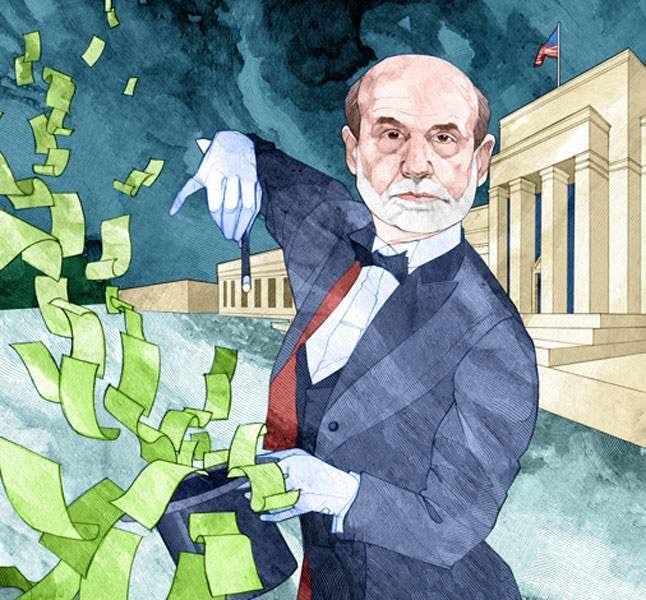

Stephen Hill on Ben Bernanke’s confident piloting of the Federal Reserve in the face of an unbelievable crisis

With the publication last October of Ben Bernanke’s QE apologia, namely The Courage to Act: A Memoir of a Crisis and Its Aftermath, we can now read the mind of the former chairman of the Federal Reserve as he battled to fight off a total global economic collapse in 2007-09. He didn’t do it on his own, as he readily admits, but he was in the eye of the storm for certain, and what he did achieve was undoubtedly the fending-off of Great Depression II.

After a strict Yiddish upbringing in the small town of Dillon, South Carolina, where segregation still persisted much to his discomfort, and where his parents had a pharmacy on Main Street, Bernanke studied hard at Harvard and then went on to MIT. Here the study of economics became his all-consuming passion, especially the 1929 collapse on Wall Street and the Great Depression. In particular, the analysis by Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz of the causes of the Great Depression — namely the widespread lack of any liquidity — caught his eye and became his central investigation. Their book, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, became his inspiration, his working Bible.

He realised something very important here: that the whole financial system is an integral part of the economy, as its main function is to keep credit flowing, down to all levels of society, to ease the wheels of industry and commerce, and everyday social and local life too. If the banks, right down to the much smaller community banks, are not there to function and serve the community, then the whole economy cannot operate. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, no fewer than 9,700 US banks failed — about 40 per cent of the total.

In 2007 Bernanke followed Alan Greenspan as chairman of the Fed. The events that unfolded out of a clear blue sky, seemingly from nowhere, in 2007-08 must have made him dizzy, but he kept his calm and his poise and thought hard constantly about what he could do with his only tool, monetary policy, with his close comrade-in-arms and advisers at the Treasury and especially the New York Fed, and his teams at the Fed in Washington.

Hank Paulson as Treasury secretary and Tim Geithner as head of the New York Fed were the other vital players, without whom Bernanke could not have succeeded as he eventually did. His first impression of Paulson tells you all you need to know: ‘Rangy and athletic, with a broken pinky finger that sticks out at an odd angle, Hank looked like the Dartmouth all-Ivy football lineman he had been when he earned the nickname “The Hammer”. Nearly bald, with blue eyes behind wire-rim glasses, Paulson projected a restless energy that took me some time to get used to.’

Paulson had the chutzpah, and then some, to sell the $750 billion TARP (Troubled Asset Relief Program) bail-out of Wall Street to a disbelieving Congress that was determined not to be hoodwinked by an ex-Goldman CEO bailing out his Wall Street pals at the height of the crisis; Paulson and Bernanke convinced the politicians that the crisis was for real, at their second attempt, which was the vital beginning of economic salvation.

Geithner, a young financial shrewdie, also had the flexible mind to realise that the financial system just had to be saved. His dry humour and poker face kept Bernanke going at times, and among his sayings that stuck were: ‘That is Old Testament!’ and ‘It’s time to lay the foam real thick down the runway!’

Then came the incredible AIG crisis — on top of Bear Sterns, Lehman, WaMu, Wachovia, Citigroup, Merrill Lynch et al: the largest insurer in the world was bankrupt. If it failed it would poison pension plans and savings, especially across the US and the Far East, where it had its origins. And AIG had, disastrously, underwritten most of Wall Street’s collateral debt obligations (CDOs) and mortgage-backed securities (MBSs), now dogged by sub-prime failures which were spread throughout the world’s financial system, but especially in the US. To his credit, Bernanke swiftly organised the first urgent and massive bail-out loan: the Fed lent a staggering $85 billion to AIG.

AIG was not a bank holding company, but Bernanke bravely invoked section 13(3) of the Fed’s charter from Congress, enabling it to lend to a non-bank entity if its collapse was a threat to the whole economy. He had punched a major hole through the Fed’s traditional constraints. Then two more top-ups took the total AIG bail-out to a staggering $182 billion, including 10 per cent of the TARP at $70 billion — an incredible sum from taxpayers and their government for a private company quoted on the NYSE. The US government, however, took an 80 per cent stake in AIG, and eventually sold out for a $23 billion profit — bravo!

The TARP did exactly what it was meant to do: it saved Wall Street post-Lehman and the rest of the banking system from total collapse, and all the money was repaid with interest within six months; and under new President Obama the TARP went on to rescue Detroit too.

Then the Fed’s policy of $1.75 trillion QE I marked the turn, for Bernanke, from a financial crisis to an economic crisis, as unemployment climbed and economic output went into sharp decline, and across the world too. Bernanke launched two confidence-building initiatives: forward guidance from the Fed on interest, and the bank stress tests to highlight capital deficiencies.

The Fed’s brief from Congress is twofold: to maintain price stability and full employment. QE I was designed to turn banks’ holdings of up to $1.25 trillion of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac MBSs, plus $200 billion into buying their direct debt, and $300 billion purchases of treasuries, putting cash into the banks so that they had the liquidity to keep on lending. Following the announcement of QE, the Dow rose more than 40 per cent over the next nine months, in a phenomenon that came to be known by the happy market-makers and their investors as the Bernanke Put.

Next, QE II was designed by Bernanke as a maturity extension program, financed by the Fed selling its short-term securities and buying long-term securities, to keep interest rates down. Unemployment, however, remained stuck doggedly at over 8 per cent: that translated into 12.5 million unemployed, with another 8 million in part-time work who wanted full-time employment, and 2.5 million who wanted work but had given up looking.

America was on the point of losing social cohesion, but Bernanke’s calls to Capitol Hill to help with fiscal measures alongside his monetary policies fell on deaf ears in a gridlocked Congress. QE III was therefore the first ever open-ended commitment by the Fed, financed by creating bank reserves, to keep buying in $85 billion a month of treasuries and MBSs until unemployment was below 6.5 per cent; in fact QE III continued, but eventually on a slow tapering-down basis, until unemployment was down to a more normalised 5.7 per cent, when Bernanke retired in 2014.

As Bernanke admits, the open-ended, dateless, QE III was in poker terminology an admission that ‘the Fed was all in’. The perfect central banker’s career, however, during the greatest financial crisis ever seen, was, with the ending of QE III and with recovery rising, a parabola of perfection.

The Fed’s balance sheet before the crisis totalled $800 billion; at the end of QE four years later, and a lot of criticism later, it stood at nearly $4.5 trillion. What was Bernanke’s plan to unwind this tidy asset haul? Why, just hold the securities until maturity — why ever not, indeed? Between 2009 and 2014 the Fed remitted profits of $470 billion to the US Treasury, more than triple the remittances from the six years before the crisis.

What did Bernanke leave out of his autobiographical account? Quite a lot, especially why the Fed never saw the global credit crunch coming until it was too late, or whether the ultra-low interest rate policy it pursued from 2005 stoked the sub-prime crisis and led to the splicing and dicing of mortgages on Wall Street, to create the higher-yielding CDOs and MBSs, that truly bust the system.

Perhaps he thought it best to let the past stay buried, particularly as the Fed was the epicentre of the failure. Central bankers wield immense power but don’t finger each other. Bernanke, however, proved his lifetime theory in the most difficult of circumstances imaginable. And it is well worth studying his eminently readable account of his courage in facing an unbelievable crisis.

Illustration by Richard Beacham