Kent is leading the exciting evolution of English wine, writes Clive Aslet

What a year 2017 was for English wine. The best of times, according to the Wine and Spirit Trade Association, which reveals that nearly 4 million bottles were sold – almost three times the figure for 2000.

On the Simpsons winery in Kent, however, disaster. Charles and Ruth Simpson, famed for the success of the Domaine Sainte Rose in the Languedoc, had bought what they thought was the perfect patch of the North Downs: south-facing, wind-protected, blessed with chalky-flinty soil that would make a farmer weep but a winemaker dance with delight – and frost-free. But oh dear, when the thermometer fell in mid-April last year, after bud break, the vintage was a write-off.

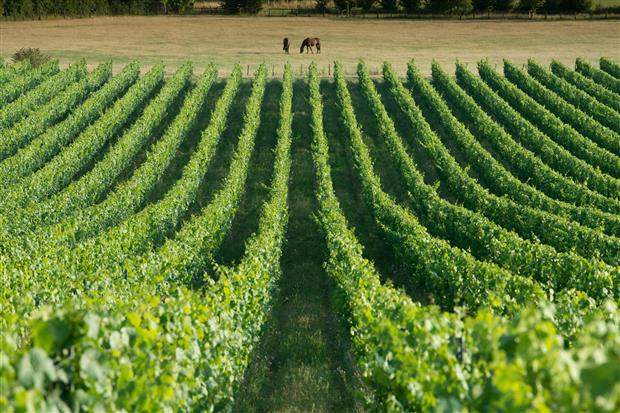

Kent, the Garden of England, was known for orchards, hops and cobnuts. None of these crops is quite what it was. But winemaking is seriously on the up and transforming the countryside. ‘Vineyards,’ says Josh Donaghay-Spire, the winemaker at Chapel Down, ‘employ a lot more people than arable farms.’

There are reasons winemakers come to England. One is the land. Not just the quality, but also the price. In Champagne, a hectare of land costs around €1.5 million. In Kent, agricultural land fetches £25,000. But then this is the winemaker’s equivalent of unbroken prairie, which he’ll need to churn up before a single vine is planted.

There’s something of the frontiersman about the Simpsons. Ruth drives me out to one of their fields and explains the lie of the land: ‘That line of old lime trees provides shelter. The sea is only a few miles away, which has a stabilising effect on the temperature.’ Her reaction to that frost? ‘We immediately ordered some huge tow-and-blow fans from Turkey to stop it happening again; they’ll blow the cold air off the vines.’

Inside the winery, Charles shows off another bit of kit: an inert press for the grapes. It keeps oxygen out while pressing, to preserve the freshness of flavour and colour. Presses of that kind aren’t allowed in Champagne; English winemakers can innovate. In 2016, the first 680 bottles produced here – the appealingly named Roman Road Chardonnay – started what is practically a cult.

Chapel Down, based near Tenterden, is the biggest wine producer in the UK – with an ambition to triple in size. Josh is so passionate about his product that he sees me just as his wife is about to have a baby. He’s a local. He started working in wine bars, then Vinopolis, went to South Africa and worked on a harvest, took a degree in viticulture and oenology, and, spotting the similarity between the aromatic wines that can be made in England and Alsace, went there for a while, as well as Champagne.

The Chapel Down style is fresh and joyous. Buy just 2,000 shares and you qualify for a 30 per cent discount on wine (BlackRock is among the bigger investors). Kit’s Coty, named after a Neolithic monument near one of the vineyards, is the premium line; I’m

in love with the blanc de blancs. They’re also experimenting with Chablis-style Chardonnay. As Josh says, ‘We don’t know how good English wine can be.’

Clive Aslet is a contributing editor at Spear’s

Related

How Tudor brickwork inspired a Lutyens masterpiece

Pillars of virtue: why marble is back in architecture