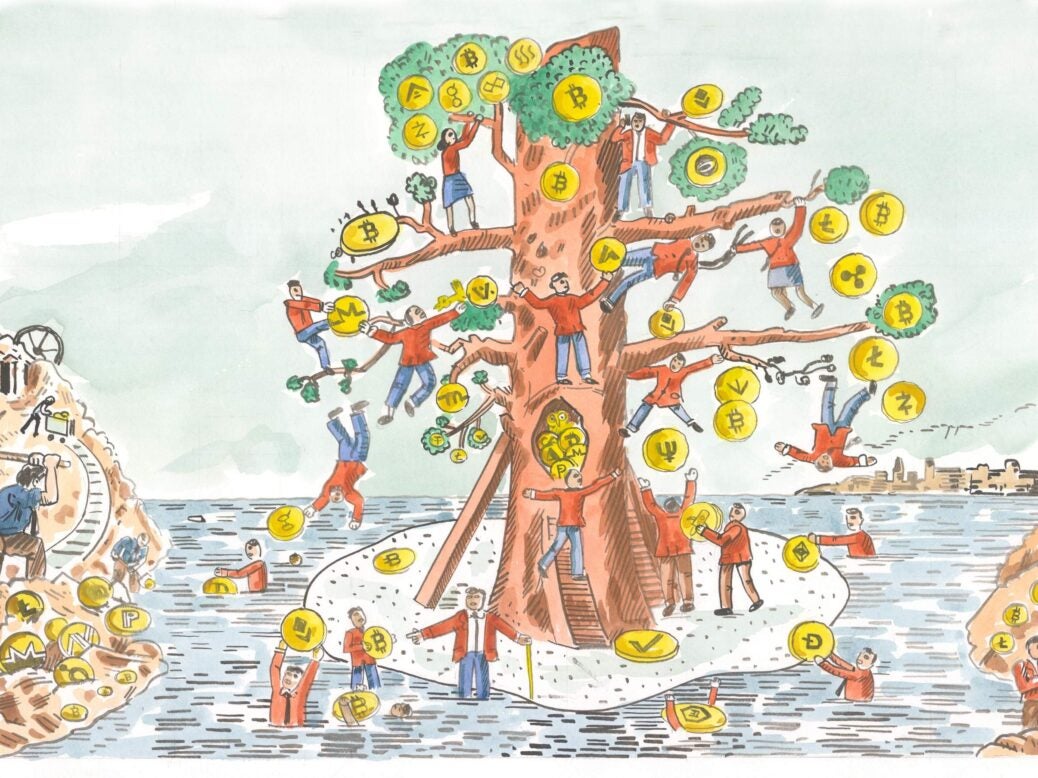

With the combined value of cryptocurrencies now north of $300 billion, blockchain is changing the world of wealth fast. Are you part of the revolution? Christopher Jackson reports

It’s an instructive exercise to enter the halls of a UK wealth management firm and ask the people there what they think of cryptocurrency. ‘We are not keen on crypto-currencies,’ says Daniel Pinto, CEO of Stanhope Capital. ‘I don’t really understand them,’ confides one CIO in a boutique firm with $10 billion in assets under managment.

The industry is naturally sceptical about any asset which, apparently worth £15,000 at the beginning of the year, is now valued at £5,000. ‘I’ve spent most of my career avoiding dodgy investments: we’re a professional firm and our job is to protect wealth,’ explains Petronella West, director and co-founder of Investment Quorum.

The ground note is wariness, but one thing you’ll never meet when the subject of cryptocurrency is raised is indifference. Always there’s an excitement in the air – the thrill of making money quickly, yes, but also something else – the anticipation of a sudden shift that will affect every level of society. Even in the sometimes staid world of Mayfair, there are those who are prepared to entertain the idea of investing in crypto: ‘They’re great to trade but we don’t consider them in the same basket as stocks and bonds,’ says Mark Ward, head of execution trading at Sanlam, who is prepared to recommend an ETF linked to blockchain companies to clients.

‘In theory they are interesting,’ adds Andrew Wilson, CIO of Lockhart Capital, ‘and we can absolutely see why a slightly younger investor might benefit from tucking away a diversified mix of them.’ Edward Lawson Johnston, a partner at LJ Partnership, agrees: ‘It’s an area which we’re trying to educate ourselves on. I spend a lot of time in the US and they’re ahead of us in so many respects.’

Weeks later, I am in New York to test Lawson Johnston’s claim myself. At a cryptocurrency seminar at the Yale Club, I note an immediate difference in atmosphere: everyone has a vibrant and essentially evangelical energy.

Everyone here owns bitcoin – but the thing they’re really excited about is the technology that sits under cryptocurrency: the distributed ledger known as blockchain. Among those sipping champagne is Chad Arroyo, the young chief marketing officer of Seven Stars Cloud – a company whose mission is to convert traditional financial services into ‘the asset digitisation era’. A genial disruptor, Arroyo seems to have more thoughts at any one time than can be articulated sequentially: ‘We’ve seen this explosion since 2009 until now,’ he says. ‘Everyone is tuned in to the price of bitcoin. But the market cap of this is still well under a trillion dollars. The larger opportunity here is in securities tokens – a security instrument represented in the same cryptographic form as a bitcoin that lives on a blockchain as a smart contract.’

It’s the scope of potential change that excites Arroyo: stocks and debt, derivatives and real estate – all these could soon be held as ‘tokenised assets’, and transferred peer-to-peer without paperwork and with a fraction of the manpower, more or less in real time. ‘Blockchain unlocks a lot of capabilities and potential for transparency and automobility,’ he adds. ‘It unlocks trust: that’s why we hire a lot of lawyers, auditors, and compliance officers – to create trust in transactions. Now you can introduce trust at the data layer.’

To listen to Arroyo is to be transported with startling rapidity to the coast of utopia. How soon will the New World be ushered in? ‘It will depend on the regulators,’ he answers. But progress at the moment is frustrating, he says. Does this dim his enthusiasm? Not at all. ‘The second a plan gets adopted there will be spend, and there will be an accelerated growth curve,’ he predicts.

Regulation. It’s the chief objection among crypto sceptics. If something isn’t properly regulated and taxed, it’s inherently risky. If your bank account is hacked, your bank will foot the bill; no such protections exist in cryptoland. Back in London at a Spear’s cryptocurrency briefing (see page 22), Alan Miller, the founder and CIO of SCM Direct, comes armed with printouts of the countries that have most Googled cryptocurrencies: from Venezuela to Ukraine, it doesn’t make encouraging reading. ‘Does this not give you any concern?’ he asks, to laughter in the audience.

But it would be wrong to imagine that cryptocurrency and blockchain are wholly illicit – attractive as they are to money launderers and drug dealers. On 14 May the Financial Times reported that HSBC had completed the first trade finance transaction using blockchain on behalf of US agricultural group Cargill: what would usually take weeks took hours, and was cheaper and paperless, too. Meanwhile, a recent survey by deVere found that 35 per cent of wealthy investors will have exposure to cryptocurrencies by the end of 2018. And in the US, SALT Lending has already issued $40 million in asset-backed loans aimed at investors in cryptocurrencies. It offers ‘blockchain liquidity without selling’ and lends up to 60 per cent of the market value of blockchain assets.

Iqbal Gandham, UK managing director of social trading and multi-asset brokerage company eToro, has installed himself in Canada Square at the heart of the banking industry. With a sweeping gesture at the sky-touching offices of JP Morgan and Credit Suisse, he wonders how much of this will be here in 50 years’ time.

For Gandham, crypto is a welcome revolution and wealth managers are not serving their clients properly by missing out on the returns that bitcoin, and a couple of the other cryptocurrencies, provide. He speaks with settled confidence about the advent of cryptos, and poses the question: ‘Will these cryptocurrencies just become an asset class or will they become currencies?’ Then he answers it himself. ‘For bitcoin to work as a currency, you need its value to go up, and for that to happen you need institutional investing. When its value is high enough, people can start spending it.’

Will that happen? There are 21 million bitcoin, Gandham points out, but there are 100 million satoshis within each bitcoin. ‘That means there are 2,100 trillion satoshis. That’s a currency,’ he says, simply.

Gandham is less worried about bitcoin volatility than the typical wealth manager. The stock market is volatile too, he says, and the bumpiness is a natural offshoot of a technological breakthrough driven by start-ups. ‘We as consumers have access to a technology at its early stages,’ he explains. ‘If you look at Facebook’s or Twitter’s price in their first three years, there was volatility – but it was only apparent to the early-stage investors.’

For Gandham the revolution is clear, and imminent – in fact to a large extent, it’s here. But back in Manhattan, when I ask Arroyo about what will happen to people carrying out intermediary functions, he winces slightly before saying: ‘Maybe instead of having five people in a compliance department, companies have additional resources for marketing or business development.’

The world of crypto is full of a libertarian utopianism – at its most extreme, it seeks a world without banks, or even governments. ‘Sometimes the crypto evangelicals talk as though banks and governments won’t fight back,’ laughs Andrew Wilson of Lockhart Capital.

Beware, then, of gigantic predictions. Yet in the history of money, if transactions can be done quicker and better, the allure is difficult to counteract. ‘The internet opened up global communication; blockchain may open up global money,’ Gandham prophesies.

Still uncertain, I head to the King’s Road to meet Jeremy Millar, the chief of staff of ConsenSys – a company with 630 employees dedicated to advancing a world based on Ethereum, an open-source blockchain platform. Millar speaks with a controlled intelligence and an accustomed patience; he is one of those people always calmly imagining the future: a world of autonomous drone taxis, and air routes ownable and tradeable as assets in real time – all fitted on a tokenised Ethereum infrastructure, of course.

‘If you take a long-term macro view, you have to be positive,’ he says when I mention concerns of job losses. ‘We have an opportunity that rivals the industrial revolution: to move human capital to more societally fulfilling tasks.’ The onus, he explains, will be on society to redirect people into meaningful work: contrary to its libertarian core, blockchain seems to imply active and imaginative governments down the line.

Then he says something that’s surprising: ‘There is no such thing today as a global financial system. There are regional systems, connected by law firms and investment banks. How you issue a share in London is different to how you do it in New York. With Ethereum, for the first time we have a real time global depository.’

What seems set to happen then, is a shift in our sense of time and space as it relates to money. We shall come to realise how slowly money had previously been moving: the lag between your buying fruit and the company that farmed it being paid will be removed; an eight-hour – perhaps eight-minute – IPO will be the norm. As we part ways, Millar says: ‘Our goal is to build fairer systems to make a better world.’ I have a sense that I am talking to a good man.

Walking back to Sloane Square, not far from where I began in Mayfair, I feel how the world has contracted for me while I’ve been studying cryptocurrency. Money is putting on pace. According to Francisco Hoyos, CEO of Swiss-based analyst Cryptalgo, the total value of world cryptocurrencies will hit $1 trillion by the end of the year. Soon, perhaps, we’ll all be living at – if not talking at – the pace of Chad Arroyo. And if you believe the bulls, we’ll all be wealthier too.

This article first appeared in the July/August edition of Spear’s magazine. Buy your copy or subscribe here

Christopher Jackson is deputy editor of Spear’s

Related

Spear’s Briefing: The great cryptocurrency debate

What do crypto currencies mean for divorce?

The rise of the crypto-philanthropist