Following the settling of Ivor Guild’s estate, Marina Griggs explains how a letter of wishes and a discretionary trust can make sure your will is executed to your specifications

The Scottish press were having a field day last week upon reports of the settling of the estate of a secret millionaire, a seemingly humble solicitor from Dundee who, it is reported, left ’26 million in his will and who has been dubbed ‘the Duke of Princes Street’.

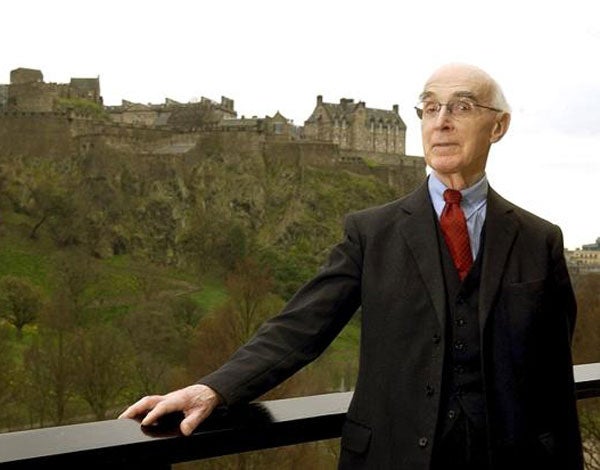

Ivor Guild sounds like he should be written into a P.G.Wodehouse novel: quite apart from the shock of black eyebrows over spectacles, the numerous reports all mention his habit of walking briskly on Edinburgh’s Princes Street most days with a hat and raincoat regardless of the weather, and the fact that he was a permanent resident in his own suite of the Edinburgh New Club (also frequented by Sir Sean Connery when in the Scottish capital).

What has undoubtedly fascinated the press most has been his level of wealth. A man who did not own a car and rarely bought anything new, settled ’26,020,030 almost entirely upon a niece and two nephews.

Unfortunately most solicitors will not be expecting to amass such a pot of gold (even if they are fortunate to inherit some wealth from their parents like Mr Guild). However, perhaps we should all take a leaf out of Ivor Guild’s book, not only when thinking both about conserving wealth when we are alive, but also when considering how to give it away.

It has not been reported exactly how Ivor Guild chose to parcel up his wealth, but if you are not leaving your estate to your husband/ wife/children, perhaps the best way of retaining some control over the dissipation of the assets and also some privacy from the prying of the press is a discretionary trust and a very clear letter of wishes. This gives flexibility to the trustees to determine the extent of each beneficiary’s entitlement, it might allow trustees to accumulate income as they see fit, or it might instruct them to distribute each year, or it could also suggest outright distributions of capital.

Importantly, for those of us who like to have the last word, a letter of wishes combined with a discretionary trust allows one to put one’s own stamp on the future, insofar as this is at all possible after death. While trustees cannot be compelled to follow your wishes, and one cannot legislate against the possibility that your trustees may go rogue (but note, there is a “clue” in the collective name given to those you choose to look after your assets), letters of wishes are generally considered to be persuasive. Furthermore it also allows a layer of secrecy without entering the minefield of secret or half-secret trusts, while a straightforward legacy will eventually become public.

However frugally you live, dying with an estate of ’26 million will be tricky to keep entirely secret.

Marina Griggs works at boutique private client law firm Maurice Turnor Gardner LLP