The death at 89 of Sir Roger Moore reminds us that there is goodness in the world, writes Christopher Jackson

It is always worth pausing to remember someone kind. It’s doubly worth doing when that person was hugely fun and reliably entertaining. Sir Roger Moore shouldn’t be allowed to go gently into that good night: he should be roundly cheered on his way.

Like all the best modern narratives, his story was essentially implausible. The son of a policeman and a cashier had little likelihood of ending up in Monaco, beloved and retired to life in a congenial tax location. But end up there he did – a cheerful monument to the largesse of the movie gods who, now and then, pluck someone out of obscurity to let them alter a little the tenor of the times.

Perhaps his beginnings gave him access to a valuable self-deprecation. Moore was never a person to envy, because he knew his good luck: ‘As always, I just played myself,’ as he likeably said in relation to his performance in The Saint, in which he starred for 118 fame-making episodes.

Over time – and especially after taking on the role of James Bond – Moore made money, yes, but he was always noted for his generosity. There are not many movie stars who devote so much of their time to charity: his very benevolence struck one as old school, an established way of doing things. His work since 1991 with UNICEF, as a goodwill ambassador on behalf of children, prefigures the efforts of a generation of celebrities since. His efforts on behalf of Kiwanis International’s Worldwide Service Project helped raise $91 million for the elimination of iodine deficiency.

For Moore, fame and wealth were not static concepts – they were opportunities to wield against injustice. ‘Never leave anyone behind,’ was his motto. He didn’t.

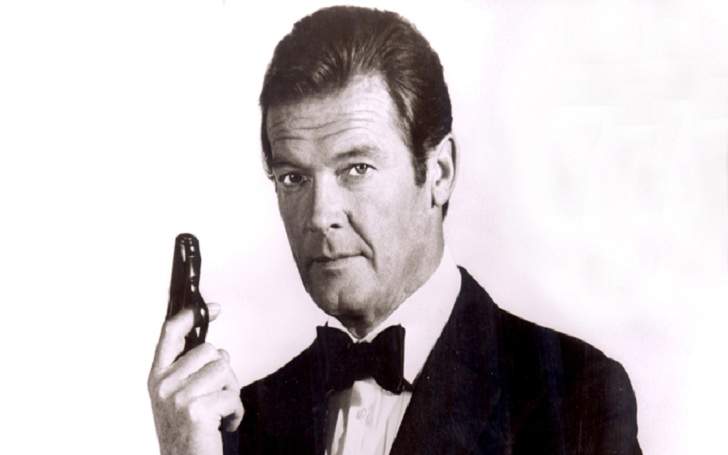

But he also entertained – which is another kind of battle, against boredom. His rendition of James Bond will always be a reason to smile. Moore had the gumption to make a Scottish assassin essentially fun: in doing so he added to the world’s allotment of joy.

Are there moments one particularly recalls? In a way his life was one long moment of Rogerness. Whether examining a Fabergé egg in Octopussy with a raised eyebrow, or looking with good humour on the wooden acting of Barbara Bach in The Spy Who Loved Me, Moore went through life with an admirable security of self which not even the apparent requirement of acting – to inhabit other people – could seriously derail.

By his own admission, Moore was the opposite of protean. He was a sort of happy rebel in his profession – like a writer who will not describe, or a painter who refuses verisimilitude. He went his own way – a cheerful low achiever (he once said he had given up acting in 1958), who nevertheless left his imprint on people. To watch any episode of Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon’s The Trip, with their superb impressions of Moore, is to realise the world’s need of him: Moore was the sort of man who can be completed only by other people’s affection.

Heaven has gone out of fashion these last years – it has reviews as bad as Moore’s own performance in 1990s Bullseye! alongside Michael Caine. But a cricket fan was once asked whether there is cricket in heaven. ‘Of course,’ he said. ‘It wouldn’t be heaven otherwise.’ It is possible to submit that heaven is equally implausible without Roger Moore. Without him, paradise would be – as we are now – a good man down.

Christopher Jackson is head of the Spear’s research unit