A decade on from the Mumbai terrorist attacks, India’s second largest city reflects a country looking to the future, writes Christopher Jackson

The Gateway to India stands, a pair of stone shoulders in a stubborn mist. One’s European knowledge of fog assumes this to be a brief weather mood, but it turns out to be a constant fact about life in Mumbai. This fog is not without its aesthetic value, but it makes you worry for the lungs of this smog-encumbered people.

The touristy parts of Mumbai are full of venerable-looking Indo-Saracenic buildings not more than a century old, while the great gate was finished in 1921, after the foundation stone was laid for the arrival of King George V and Queen Mary in 1911. The Gateway looks like it’s crying out to be a symbol of something. For once, that’s actually plausible: it’s a portal that leads you from one way of being, the western, to another way of life – the east. Today’s India is the result of that encounter.

For some, this was an exciting meeting, while, for others, it was a clash. In India, mobility and migration are continually rubbing up against indigenous culture. To the Westerner’s eye, that can have pleasant ramifications: the longer you stay here, the more a certain, distinctly un-English, cheer reveals itself as integral to the city’s rhythms. A rickshaw traffic jam that would make a Londoner hop with rage engenders a pervasive hilarity among locals. On a morning temple visit, I discover Hare Krishna worshippers singing in their work clothes; religion is integral here.

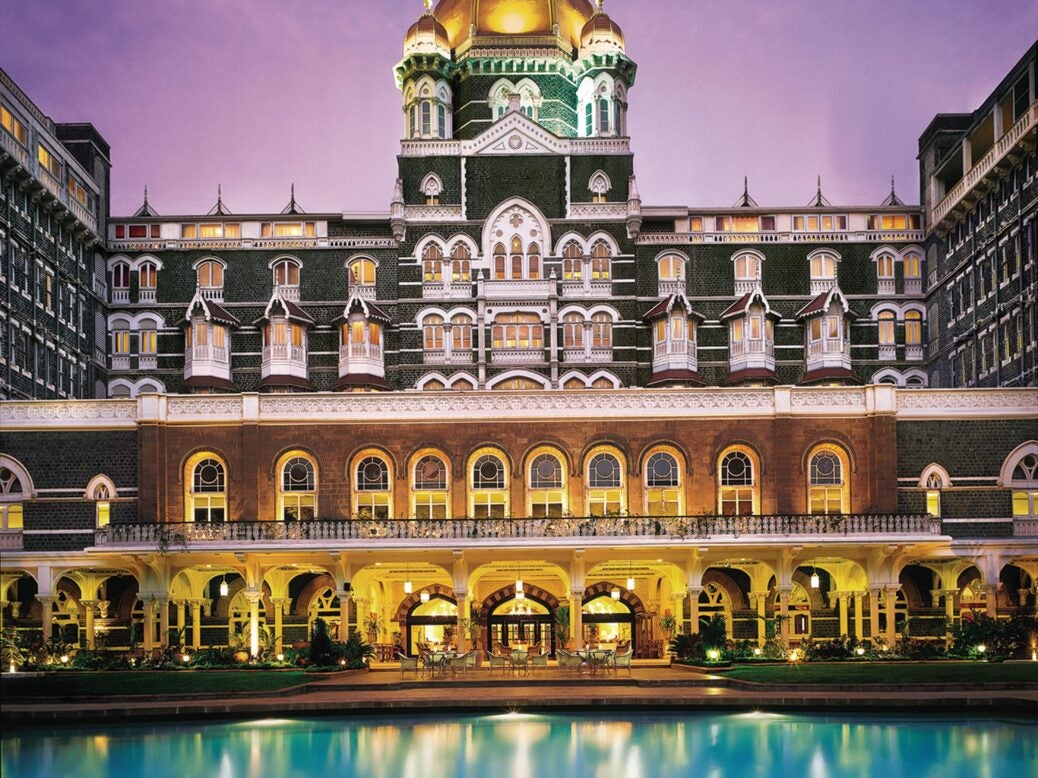

Opposite the Gateway, and just a hundred yards from the seafront, stands The Taj Mahal Palace hotel. From the promenade, it seems to be a building of unassailable confidence: like so many five-star hotels, it projects the forbidding look of a place not everyone has the right to enter. Outside it, you find evidence of vulnerability in the intense seriousness of its security arrangements.

The ghosts of Taj

The Taj has a complex history: owned by the Tata family – that Westernising dynasty synonymous with an India assimilated with the modern world – its architecture is heterogeneous, comprising elements of European, Islamic and Indian influence: it’s an image of world-culture. It was India’s first taste of the essentially international language of luxury: it became – overused word – ‘iconic’.

But being iconic – as the world found out on 26th November 2008 – made it vulnerable to attack by Lashkar-e-Taiba, an Islamic terrorist organisation based in Pakistan. There are few images of that day – nothing to compare with the 9/11 falling man. The impression is of a scene whose horror was its claustrophobia. The imagery is eloquent in its way: one finds the famous façade wreathed in smoke. These are exteriors, which suggest unbearable scenes within.

The opulence contains a melancholy; it is possible to imagine that there are ghosts here. There is, for instance, the guest book signed by President Obama referring to the staff’s ‘resilience’. And here is the memorial wall being built to the fallen. Even the pool – a place of necessary refreshment after the heat of the city – retains the association that it was once the scene of shooting. One can’t help but reconstruct the incident in the mind.

But to wake early, as I did, and venture out into the city to see the morning fish auction is to realise all over again how unattainable the terrorist’s goals are. Nowadays, the boats must head further afield than ever before. The sea, emptied by human appetite, must continue somehow to feed a city which isn’t liable to get any less hungry any time soon. But this is life – the struggle for survival and the need for innovation.

Then it’s off to watch the newspapers salespeople begin their day, balancing their papers, in strapping-enmeshed towers as they wobble off, precariously at first like children learning to ride, into the literate city.

I head down also to the flower and vegetable market. This is adjacent to one of the main stations, and I stand on the platform as the train pulls in. Once the doors open, there’s a Darwinian rush into the carriages as purchasers cram both themselves and the morning’s purchases into the small available space. But the rush to the carriage isn’t as hard fought as it may look; everyone collapses in laughter. There’ll be another train along in a moment.

Hyderabadi riches

Throughout, one keeps coming up against the sheer enormity of India. Hyderabad, where I head to next, is India’s fifth biggest city, and larger than London. There, the Taj has another property atop a hill: Falaknuma Palace once belonged to the last Nizam of Hyderabad, the favourite of his 35 palaces. His kingdom was lost in the end – a victim of partition – but the palace remains a monument to former riches.

Hyderabad also contains one of the more emotive buildings in India, and now is the time to visit before it is turned into just another museum. This is the old governor’s house, or Koti residency, where James Fitzpatrick, the British Resident at Hyderabad from 1798 to 1805, lived. Fitzpatrick converted to Islam and, in the teeth of much scandal, married a local Hyderabadi woman named Khair-un-Nissa.

This building is an example of the way in which East and West have collided down the years. It now has a Palladian façade – inside you can feel, in the ambitious shape of the place, a certain faded grandeur: what once was high society now serves as a symbol of dilapidated empire. It is moving to consider that the house’s restorers can’t be sure which rooms were used for what.

Lessons from history

It’s a vivid lesson in how rapidly the currents of history can collaborate in the unpicking of power structures. Beyond the house is a graveyard full of those who came here as part of the empire project: they are buried in important-looking tombs, and couldn’t have known how quickly their final resting places would succumb to the weeds.

The Fitzpatricks’ is a moving story because it works exactly against the terrorist narrative: theirs was a story of love, and of a bridge built by that love between cultures. But they were also vulnerable to the same currents as us all – to rise and fall, and vicissitude. The 19th century belonged to the British; the 20th to the Americans. This one already seems to have something to do with China, but also with India. So it goes.

Back in Mumbai, I prepare to leave. As I look out from the coast at the Bandra–Worli Sea Link, suspended within the grey like a disembodied bridge seen in a dream, one feels admiration for this city. It has great challenges ahead – but nothing can change the fact that it’s a part of our collective story now.

Christopher Jackson is deputy editor of Spear’s