Modern monetary theory was once the preserve of left-wing utopians. But as governments around the world continue to pile on debt, it’s gaining currency

On 22 June 2010, the word ‘deficit’ was embedded into Britain’s political lexicon. That was the day the 38-year-old chancellor George Osborne delivered what the Daily Mail later dubbed a ‘bloodbath’ Budget.

The newly minted coalition government, Osborne said, had inherited from its predecessor the ‘largest budget deficit of any economy in Europe’. The policy of the new government was, therefore, to ‘raise from the ruins of an economy built on debt, a new, balanced economy where we save, invest and export’.

In his speech, which mentioned that D-word 18 times, Osborne promised an economy ‘where the state does not take almost half of all our national income, crowding out private endeavour’.

Osborne’s efforts to trim the deficit would be the leitmotif of his chancellorship.

In an effort to make good on his pledge, he ushered in an era of austerity, resulting in £30 billion of cuts between 2010 and 2019, reducing funding in areas such as local government and welfare.

A decade later, the UK’s deficit is set to be three times what it was when the coalition government inherited a ‘bankrupt’ Britain.

As the UK wrestles with the fallout from the coronavirus pandemic, public debt is on track to reach £290 billion this year, or 14 per cent of national income – the highest level in peacetime. Despite these figures, Boris Johnson’s Conservative government has already ruled out a return to austerity.

At October’s Conservative Party conference he doubled down on the commitments outlined in the Budget in March, when the government pledged to ‘level up’ the British economy with £600 billion of infrastructure spending on projects such rail and road, affordable housing, broadband and research over the next five years – the highest in real terms since 1955 and a tripling of the average annual net spend over the past 40 years.

In his March Budget speech, Johnson’s 39-year-old chancellor Rishi Sunak mentioned the D-word just once. What happened, British taxpayers might ask, to balancing the books?

For economists who espouse a once niche but now increasingly popular school of thought known as modern monetary theory (MMT), the books did not need to be balanced in the first place. MMT advocates believe it is wrong to think of government spending as analogous to the budget of an individual household, which must live within its means and avoid spending more than its income.

They argue that governments that issue their own currencies are incapable of running out of money, because they have the power to create more. Government spending should, therefore, be constrained not by deficit levels, but by their implications for inflation. The only other limiting factors are real resources such as workers or supplies.

What’s more, MMTers say, many of the traditional roles of monetary policy – such as keeping prices stable and pushing toward full employment – should be fulfilled by fiscal policy. Taxes should function not to fund government spending, but as a tool to remove currency from the economy to prevent it from overheating.

Under MMT, with a licence to print money, governments do not need to issue bonds in order to borrow. Instead, bonds act as a way to remove excess reserves from banks in order to meet interest rate targets. Debate on the topic is complicated and technical.

But one of the most central tenets of MMT is simple: that thinking differently about ‘balancing the books’ would radically improve governments’ ability to push towards full employment and fund ambitious spending projects that would improve citizens’ quality of life. Until recently, the vast majority of conversations about MMT were between bloggers and unfashionable academics, not policymakers.

That the theory is now being taken more seriously than ever is largely down to the economist Stephanie Kelton. A professor at Stony Brook University, she was an adviser to Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign in 2016, when she was named by Politico as one of the top 50 ‘thinkers, doers and visionaries transforming American politics’.

Earlier this year, Kelton published The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy. The book addresses what she sees as the central ‘myth’ surrounding deficits – that they are inherently bad – and has become arguably the most talked-about economics book of 2020.

That’s no mean feat in a year where Thomas Piketty and Paul Krugman have published too. Kelton’s – and MMT’s – place in mainstream politics was confirmed earlier this year, when she became a member of Joe Biden’s economics ‘taskforce’. Some of Biden’s spending pledges, such as a $2 trillion climate pledge, appear to bear Kelton’s mark.

***

Speaking to Spear’s from her home in New York, Kelton traces the start of her interest in MMT to the Nineties. As a graduate student at Cambridge she encountered the work of Hyman Minsky, whom she considers ‘part of the bedrock of MMT, as it’s broadly understood today’. Some of Minsky’s ideas about theories, such as chartalism – the view that, rather than a commodity, money is a ‘creature of law’ – would influence MMT’s founding fathers.

By the autumn of 1997, Kelton was at the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College in New York, writing papers critical of the euro and the Maastricht Treaty, with British economist Wynne Godley.

‘We were really voices in the wilderness,’ she recalls. While most of mainstream economics at the time viewed the euro as an ‘efficiency project’ that would reduce transaction costs and emphasise monetary policy over fiscal policy, the institute had a ‘very different mindset’, she recalls: ‘For us, fiscal policy is a much more durable, reliable, important policy tool, and giving up currency sovereignty was going to be a problem.’

Kelton remembers writing that the move could open European countries up to a debt crisis. The turning point for MMT, Kelton says, came in January 2019.

With US national debt already at $22 trillion, Democrat representative and self-described ‘democratic socialist’ Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said that MMT ‘absolutely’ needed to be ‘a larger part of our conversation’ about policy. (The Democrat politician may have had in mind her own proposal for a ‘Green New Deal’, which she estimated would cost at least $10 trillion.)

Ocasio-Cortez got her wish. MMT became an increasingly prominent theme in public discourse. It was a major plank of Andrew Yang’s campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination, but the reception it received was largely frosty.

‘Many mainstream economists no longer ignored us, but they didn’t start to take us seriously – they started to attack us,’ Kelton laughs. BlackRock CEO Larry Fink called the theory ‘garbage’, while Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell slated it as ‘just wrong’. Warren Buffett declared himself ‘not a fan’.

The main objections to MMT, from those who deign to take it seriously, are that it is irresponsible, that excessive deficit spending risks hyperinflation. Attempts to mitigate this through taxation, critics say, would lead to biting recessions.

‘Do the math, and it becomes clear that any attempt to extract too much from seigniorage [printing more money] – more than a few per cent of GDP, probably – leads to an infinite upward spiral in inflation,’ wrote Paul Krugman, one of MMT’s most vocal critics, in a searing op-ed for the New York Times. ‘In effect, the currency is destroyed.’ Such was the low opinion of MMT that in a survey of America’s 42 ‘top’ economists by the University of Chicago Booth School of Business that was commissioned shortly after Ocasio-Cortez’s intervention, not one respondent agreed with the theory’s ‘basic aspects’. Then the coronavirus pandemic happened.

***

In order to mitigate the damage done by dramatically contracting economies, governments and central banks have wielded their power in a way not seen since the Second World War. The budgets of households, companies and government departments have been subsidised. And, as many forecasts show, the bill will be considerable.

The pandemic is expected to cost the UK government £210 billion for the first six months alone, according to the National Audit Office. Coronavirus is set to push the US federal deficit to $3.3 trillion in 2020, more than triple the shortfall posted in 2019. In May, wealth manager Pictet went as far as to say that the US is already in a ‘soft’ MMT regime. In a report, the firm said that federal debt is being viewed as an ‘important but secondary’ concern by the Fed.

It is engaging in ‘explicit’ yield curve control to monitor interest rates, and the official mandate is to target inflation and full employment. ‘US policymakers’ bold actions in response to the coronavirus bear some traces of the free-wheeling deficits, repressed interest rates and central bank activism (money creation) that form the cornerstones of the MMT playbook,’ the report says.

So far, none of the critical assessments of the likely consequences of MMT have been realised. Perhaps this is because the true economic effects of the pandemic are yet to be borne out. But higher budget deficits have not led to higher interest rates on public or private debt, and inflation remains low.

Economic orthodoxy dictates that large deficits result in high interest rates, which in turn ‘crowd out’ private investment and hamper the economy – because they discourage businesses and individuals from taking on debt to invest in projects that spur growth. But this has not held under current conditions, says Thomas Costerg, a senior economist at Pictet and co-author of the firm’s ‘soft MMT’ report.

The wealth manager expects the current state of play to persist, at least until the end of the next presidential cycle in the US. There is a chance – a small one – that governments could begin to lurch to a purer form of MMT, where fiscal and monetary policy are loosened further. In this scenario, Costerg says, central banks might even inject money directly into bank accounts, and would probably lose their independence from government treasury departments. This, he argues, could increase the risk of financial instability, lead to waves of ‘bubbles and bust’ and fuel ‘public mistrust’ of policymaking.

If governments were to embrace MMT in this way, Costerg believes there would be ‘a high risk’ of a slide into economic chaos and a loss of confidence in the currency. Inflation, ‘if not hyperinflation’, would also be possible, he says.

John de Salis, executive director at wealth manager Mirabaud, is similarly concerned. ‘Let’s not forget that if you push MMT to its logical conclusion, you end up with central banks losing a major part of their credibility, which is independence,’ he says. While credibility is one of the largest assets of a central bank, independence has been ‘a core tenet of Western liberalism’ in the latter part of the 20th century, including in the UK, he says. ‘So you’re potentially reversing a really big structural element of Western central banking.’ Indeed, despite the recent actions of governments and central banks, many – almost certainly most – economists would still consider themselves sceptics.

When Spear’s spoke with Jagjit Chadha, director of Britain’s oldest independent economics research institute, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, his assessment was dismissive: ‘MMT simply says: “We issue money and then we decide later on whether we’re going to back it with future taxes, if at all. Issuing tokens of expenditure without a clear funding plan is akin to money circulating as unfunded government debt.

It runs a severe risk of a lack of credibility and a run on the currency. It is simply not the way to develop a stable monetary-fiscal regime.’ Why, if there are such fundamental problems with MMT, has it become so popular? Chadha is blunt: ‘There are fads and fashions. I suspect some people think we didn’t fly to the moon.’

***

For Kelton, however, the shifting sands of economic policy and discourse present an opportunity. ‘You can use the insights that MMT provides, to say, “Hmm, we have really been holding ourselves back, haven’t we? We have been unnecessarily constraining fiscal policy in ways that would have allowed us to have better lives, to have better public services, to have a better-functioning economy and a better safety net. We could have been dealing with climate change.”’

To those who accuse Kelton and her fellow MMTers of being naïve, or of believing in a ‘magic money tree’, her response is forthright. ‘That’s a dismissive obviously; that’s someone who doesn’t want to engage. That’s their defence mechanism.’

And, she adds: ‘If you’ve chronically run your economy below its potential, then that’s a policy choice.’

This is an argument that will continue as the recovery from the pandemic takes shape. What is clear now, however, is that there has been a shift in the way modern economists think about deficits.

The model espoused by David Cameron and George Osborne – of countries ‘living within their means’ – has been overtaken by events.

If politicians will spend the coming months and years looking for answers, so will wealth managers and their clients. The bond market, for instance, has a ‘diminishing’ capacity as a portfolio diversifier due to the risk of inflation. You can no longer rely on the traditional ‘autopilot’ of a portfolio that has a 60:40 split between equities and bonds respectively, which became popular in the Eighties and Nineties.

There has been a ‘lot of soul searching’ among clients, Costerg adds. Even for those with the relatively modest goal of protecting their wealth, there is a problem: ‘The pool of safe assets is actually diminishing so rapidly … that’s creating a lot of anxiety.’ Gold – which is now considered by many to be more effective than bonds as a hedge against the performance of equities – has been having a moment in the sun. Its price increased 16.8 per cent in US dollar terms over the first half of 2020.

But, of course, ramping up one’s allocation of precious metals is not a silver bullet. ‘There is a need to rethink and re-discuss objectives and asset allocation, to be more creative and – I think – more human, to some degree, in this new economic context,’ says Costerg.

But even seasoned campaigners can be forgiven for feeling nervous: ‘It’s uncharted territory’. A passing fad, or the future of fiscal policy? As long as governments believe they have little choice but to put any deficit-phobia to one side, the MMT debate will continue.

According to Kelton, even people who would once have rejected the idea out of hand are now taking it more seriously. ‘I take those phone calls,’ she reveals. ‘Sometimes they come from the most unlikely places – you know, people who are self-proclaimed deficit hawks for their entire career in government […] I know they’re out there.’

This article was first published in the November/December 2020 edition of Spear’s magazine

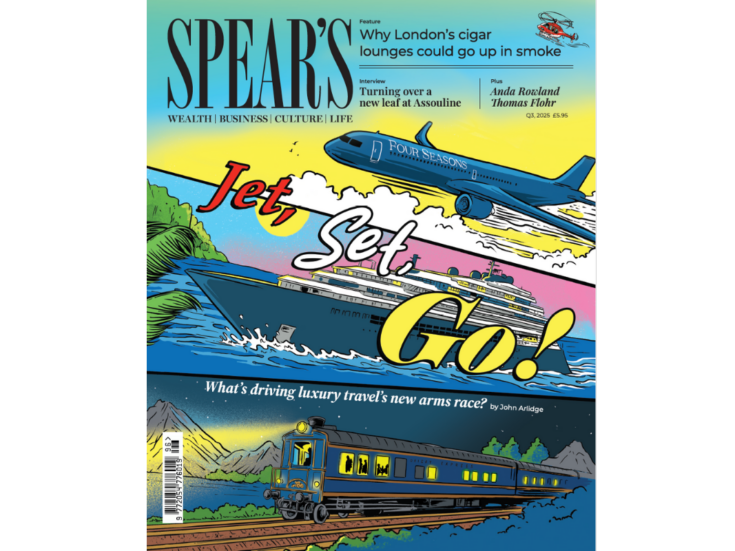

Main illustration by Klawe Rzeczy