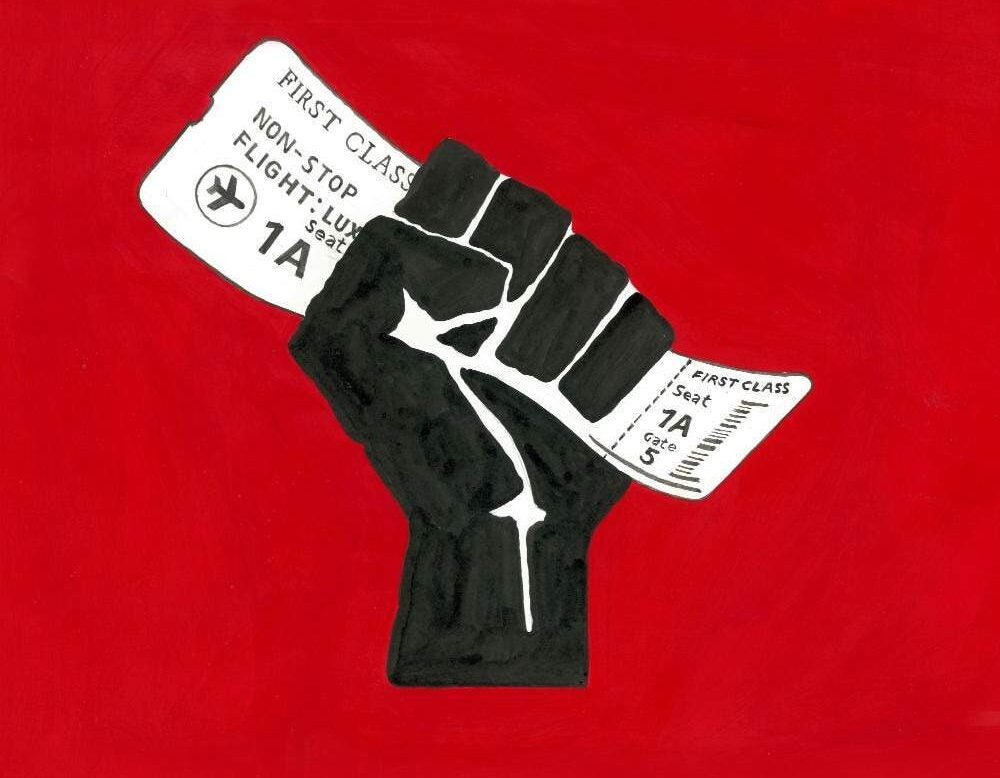

It’s the billion dollar question: How is the left winning the battle of ideas, and what can HNWs do about it? Arun Kakar talks to commentators on both sides of the argument

‘Abolishing billionaires might not sound like a practical idea, but if you think about it as a long-term goal in light of today’s deepest economic ills, it feels anything but radical.’ So declared a recent front page op-ed by New York Times columnist Farhad Manjoo, in a discussion of the moral and political arguments for taxing billionaires out of existence.

For the first time in 40 years, radical left-wing ideas have entered mainstream political discourse across the world’s advanced economies. Figures such as Jean-Luc Melenchon in France, Pedro Sanchez in Spain, Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the US and, of course, Jeremy Corbyn here all identify as socialists and are enjoying sustained periods of popular support for their ideas.

All have their sights set on the wealthy, who are being targeted with a raft of radical policies. Ocasio-Cortez has said incomes above $10 million ‘might’ need to be taxed by up to 70 per cent. Democratic presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren – who claims she is not a socialist – has proposed an ‘ultra-millionaire tax’ aimed at households with a net worth in excess of $50 million at an annual rate of 2 per cent, rising to 3 per cent above $1 billion.

In the UK, the Labour Party’s most recent manifesto pledged more than £6 billion of extra taxes on the top 5 per cent of earners, and a wealth tax has been mooted to pay for the party’s £8 billion funding boost to social care. Labour also plans to force companies with 250 or more employees to hand over 10 per cent of their shares to workers. ‘The very richest in our society have had tax breaks, giveaways and tax havens,’ says Corbyn. ‘They’re living on borrowed time.’

Yet socialism was supposed to be pushed to the margins of political discourse by what political scientist Francis Fukuyama claimed in 1989 was the ‘universalisation of western liberal democracy’. Socialism was, as Margaret Thatcher once said, a ‘disease’, likened to ‘trying to cure leukaemia with leeches’. So what’s going on?

To find out, I ask Leo Panitch, distinguished professor of political science at York University in Toronto. An amanuensis of Marxist thinker Ralph Miliband, Panitch was a socialist before it was cool. He frames the discussion of modern socialism in terms of growing inequality over the past 40 years. ‘This isn’t about seeing the wealthy as greedy and evil,’ he tells me.‘It is them being themselves elements within a system whose dynamism has driven the spread of global capitalism around the world to their benefit.’

It’s structural, in other words. And he has a point: the latest figures from inequality.org have the world’s richest 1 per cent owning 45 per cent of the world’s wealth. Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos and Warren Buffett have the same wealth as the poorest 160 million Americans – and this inequality is set to get worse. According to Oxfam, the 26 richest billionaires equal the combined wealth of the world’s poorest 50 per cent (around 3.8 billion people). Back in 2009, you needed 380 billionaires.

Quite clearly, as Panitch points out, the financial crisis that began in 2008 ‘didn’t itself have the redistributive effects that that kind of crisis sometimes does’. As a result people have started following that old idiom: don’t get mad, get equal. ‘You can protest for ever,’ Panitch explains. ‘You can protest with signs outside the IMF or the Treasury building until hell freezes over and you won’t change the world.’ But now the gloves are coming off: ‘There has been a remarkable development, this quick move from protest to politics.’

We’ve gone from the Occupy Wall Street protests of 2011 to Ocasio-Cortez being elected to Congress in 2018. ‘From protest to politics’ is embodied by Corbyn, who spent 32 years on the backbenches virtually unknown beyond Westminster.

The rise of millennial socialism

Socialism today is more than a doctrine, however. You see its arguments discussed at music festivals and bars, through memes and Facebook groups. What’s more, it’s winning the argument among young people.

In the 2016 presidential primaries, more young people in the US voted for Democratic contender Sanders than for Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton combined. Fully 51 per cent of Americans aged 18-29 say they view socialism positively. In the land of the free, that’s pretty astonishing.

One of the newer voices on the left in Britain today is Grace Blakeley, an economist at the IPPR think tank and author of the upcoming book Stolen: How to Save the World from Financialisation. Blakeley sees the narrative of the past 40 years differently from most: it’s not about the triumph of a new economic model so much as the exploitation of the financial system.

And this finance-led growth has now run out of road: ‘We’re living in a low-investment, low-wage, low-productivity growth model which was hidden before 2007 because the financial sector was booming and it boomed in the professional services,’ she says. ‘Now we’re living in the age of post-finance-led growth.’

For Blakeley – who has urged people to ‘think about the banks the way Thatcher thought about the unions’ – there needs to be ‘a lot more worker ownership, a lot more co-operative ownership’ as well as ‘changes to corporate governance in the way that nationally owned enterprises were structured’.

Blakeley isn’t alone. At the same time, headlines that Britain’s richest man, Sir Jim Ratcliffe, is able to move to Monaco in order to legally save £4 billion in tax supply the arguments of the left with increased momentum.

What wealth thinks

To find out how is wealth reacting to all this, I talk to Matthew Fleming, a sixth-generation member of the Fleming banking dynasty and head of family and governance at Stonehage Fleming, which advises on more than £45 billion of assets on behalf of families and charities.

‘A lot of the challenges to wealth aren’t new,’ Fleming tells me, recalling the ‘astronomical’ rates of taxation when he was a boy in the Seventies. What’s different this time, though, is the challenges are more ‘upfront’. Increased transparency, instant news and a ‘fascination in the media’ with the wealthy have played out in the discussions taking place today – the rich haven’t felt pressure like this in a while. ‘We’ve grown up in an incredibly benign environment for the last generation and a half,’ he says. Not any more.

In a report for clients, the firm warns frankly of ‘society’s creeping antipathy towards the rich’, and it’s not gone unnoticed. In a survey of HNWs last year, Stonehage Fleming found that 57 per cent of respondents were at least mindful of the need to appraise their contribution to society. ‘There is a more tangible feeling of guilt and a more tangible lack of comfort in the privilege and wealth that they’re going to inherit,’ Fleming notes of the next-generation wealth he advises.

For Fleming, the solution isn’t necessarily to be found in all the talk of rising taxes and redistributive policies – it’s more fundamental than that. It’s about what he terms the ‘purpose of wealth’.

‘The purpose of wealth is something that really hasn’t been debated at a political level and there is no agreement,’ he says. ‘If governments can’t figure out what the purpose of wealth is, it might actually be a mistake for families to wait until a government changes its opinion.’

For some, that ‘purpose of wealth’ now includes countering ‘social inequality and the need for environmental sustainability’ – through the investments, ownership influence, direct-employment decisions and lifestyle habits – as well as philanthropy. It shows ways the rich are on the move. And not just in the way Ratcliffe is. Instead, as Spear’s has previously reported, capital is moving in new directions, through impact investing – where portfolios are geared towards companies whose non-financial performance indicators focus on sustainable, ethical and corporate governance issues.

They’re joined by millennial new money, entrepreneurs with a social conscience who are taking concerns into their own hands. More than half of investors under 40 back impact funds, according to Barclays, compared with just 3 per cent of those over 60.

But don’t write off the greys, I’m warned by Nataša Williams, head of private office at investment firm LGT Vestra. ‘There are a lot of people who have a more dynamic outlook on life who are not millennials,’ she insists, framing this outlook in a willingness to ‘sacrifice returns’ to achieve personal objectives. ‘A lot are vegan, increasingly a lot are restricting travel and taking up a more socially responsible way of living, using their wealth and their mind more for good causes, rather than “showy-offy” aspects.’

A force for good

Some even view the challenges to wealth positively, I’m told by Charles Seaford, from the Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity. ‘Wealthy people can play an active role in pushing society in the right direction,’ he says. ‘In that way it is more of a responsibility – they actually have an opportunity.’

The academic sees the equation in blunt terms: ‘If you are a wealthy person, you need to ask yourself which you prefer – to have £50 million and the threat of total chaos, or £35 million and a relatively tranquil, progressive, safe, calm stable society. I think quite a lot of people will choose the latter.’

So what’s your choice? Many British UHNWs are already factoring in the worst-case scenario. A third of UK billionaires have moved to so-called tax havens. John Caudwell, who has boasted that his tax bill ‘is the biggest in Britain’, told Spear’s earlier this year that he’d be heading to Monaco if Corbyn took the keys to Number 10.

‘UHNWs are not bound by the views of one particular country or one particular groundswell of opinion,’ I’m told by Mark Stephens, a partner at Howard Kennedy. ‘They are almost untouched or untouchable by the ways in which society or governments want to change things.’

The crucial word here is ‘almost’. For all the pains of taxation, the intangible value placed on reputation – think of the woes of Sir Philip Green – is priceless. There are also emotional bonds. As one HNW told Spear’s not long ago: ‘Whatever happens with Corbyn, I’m not leaving. I’ve got dogs here.’

It is clear that the inflection point in politics today also represents an inflection point for capitalism, and the wealthy are starting to recognise this. From Bill Gates seeing the validity in a discussion on removing billionaires to Guy Hands telling Spear’s last year that ‘we actually need a bit of Corbyn’, the wealthy understand that the status quo needs to end. Inaction is no longer an option. After all, Monaco only has so many apartments.

Photo credit: Gage Skidmore @Flickr; Cover illustration by Adam Dant

Arun Kakar is a junior researcher at Spear’s

This article first appeared in issue 68 of Spear’s magazine, available on newsstands now. Click here to buy and subscribe

READ MORE:

Holy dope: How cannabis has unrolled a $500bn ‘addressable market’

Focus: How long has the US dollar got?

Money to burn: How investors must save the world from climate change