‘Australia’s impressionists’ at The National Gallery in London shows that the intrepid painter John Russell deserves to be better known than he is, writes Christopher Jackson

You can be forgiven for not having heard of him. John Russell (1858-1930) is one of those people history is cruel to: he is the man who left his native land at a crucial period in its development. He became respected everywhere but beloved nowhere. John Peter Russell – to give him his full moniker – has also been cursed by having the same name as a minor English painter, most noted for his pastel drawing of a gibbous moon.

But in life – as is so often the case with those who have lapsed into obscurity – he was known, and looked up to, by people history has come to know very well. Russell left Sydney and befriended Vincent Van Gogh in the early 1880s at an art school in Europe and regularly painted with Claude Monet. Henri Matisse was introduced to impressionism by him. Matisse would later say: ‘Russell was my teacher, and Russell explained colour theory to me’.

A new exhibition at the National Gallery in London shows that Matisse could have had no better teacher. Russell is, to quote its co-curator, the ‘third act’ in the exhibition, and follows Australians like Arthur Streeton (1867-1943) and Charles Conder (1868-1909) who by and large retained their Australian identity. Russell shed his – indeed the paradox of his career is that he was a great Australian who painted in a technique one naturally associates with France. But in the end this sounds like a dismissal when that is the last thing he deserves: in fact, he painted primarily like a first-rate painter.

John Russell, A Clearing in the Forest, 1891, Oil on canvas, 61 × 55.9 cm, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, A.M. & A.R. Ragless Bequest Funds 1968, © Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

It used to be said that you could walk for miles within a Claude Lorraine. I’d rather walk for miles within a John Russell. For instance, in A Clearing in the Forest (1891), the pink tree trunks and teal skies give us a sense of wonderland which doesn’t feel arbitrary or contrived, but a true depiction of an exalted mood. It is a controlled account of the sort of delight we don’t receive often enough in our hectic Twitter-ish lives – it wants to tell you as frankly and openly as possible about the world’s beauty and its continual freshness.

Russell didn’t always get it right – I’m not sure, for instance, if to begin with he was quite so good at water. In paintings like Rough Sea, Morestil (c.1900) and Rough Sea, Belle-Île (1900), the waves are a little too mannered. The program notes speak of ‘the energetic brushstrokes in this foaming symphony of blue’ but the semi-circle motifs in the water seem to me to fall on the wrong side of the cartoonish, which is where impressionist painting tends to end up when colour isn’t effectively built and line takes over.

John Russell, Antibes, about 1890-2, Oil on canvas, 16.5 × 24 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Gift of the Margaret Hannah Olley Art Trust 2012, © AGNSW

But when Russell committed to colour, how wonderful it was. For example, in his little picture Antibes (1890-2), we begin to glimpse truly radical possibilities. Here, it is as if the bond between human mood and the goings-on of nature has been gratifyingly severed. Instead, we are witnessing a raw encounter with things as they are: this isn’t an essay but a vision. Colour is stacked on colour; each brushstroke is an authoritative statement. Not, as in Clearing: ‘This is how I feel today’; but: ‘This is.’

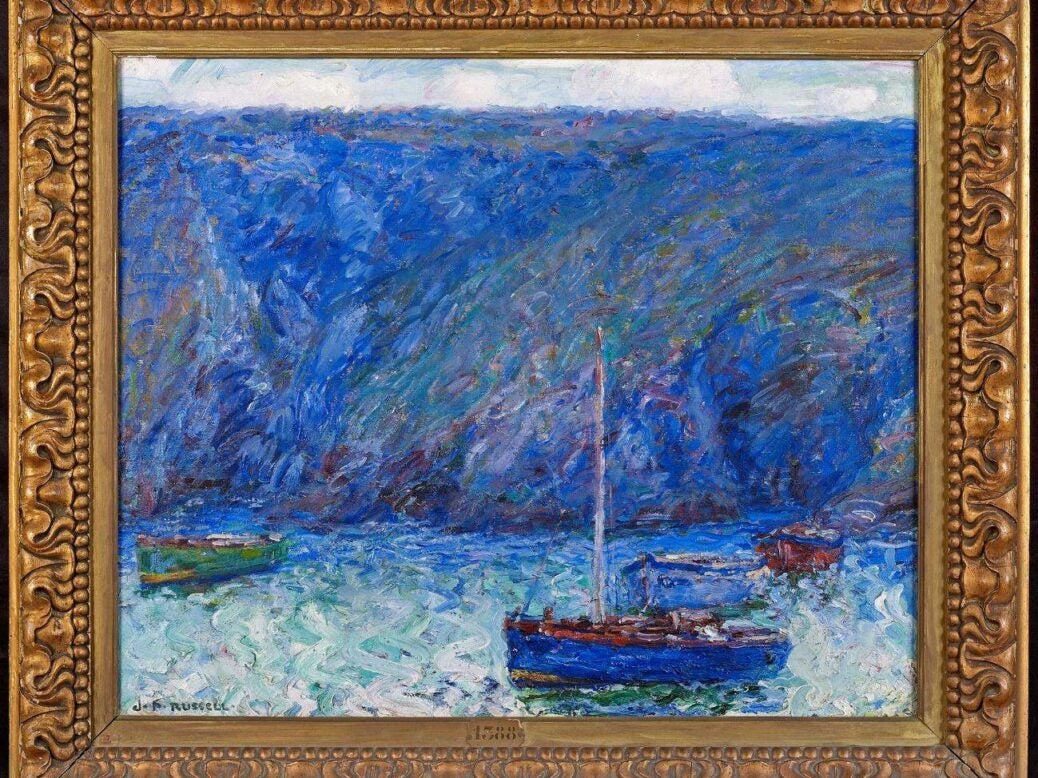

But for me the standout picture in the exhibition is Cruach en Mahr, Matin, Belle-Île en Mer (1905) (see top of page). Here Russell’s earlier difficulties with the sea have been surmounted: this truly is a symphony in blue – a great homage to the sheer power of the sea. When we are near to the sea, everything is drenched in the implications of that enormity – we feel its nearness. Here, as in Antibes, the strangeness of the world is met with an impressive authority: Russell gave the unusual the look of infinite solidity.

The accusation against Russell is that he left his homeland and insodoing diluted something valuable within himself – that he ended up somehow lacking identity, painting other people’s pictures. Whereas a contemporary like Arthur Streeton stayed and made some great Australian pictures; Russell left and created a derivative œuvre which wasn’t quite his.

On the evidence here, that version of events doesn’t stack up. I can’t help but feel that such an interpretation of his art would have seemed rather strange to Russell himself, as he stood face to face with southern France, amid a light which no doubt reminded him of his home Australia in any case. But then light is what impressionism is always about and must matter more to the artist than the tedious controversies of nationhood: if we try and pin John Russell down to a stationary Australianness then it’s we who miss out.

Australia’s Impressionists is in the Sunley Room at The National Gallery, and closes on 26th March 2017