We can learn some cautionary lessons from a new biography of Sir Philip Sassoon, the Gatsby of inter-war British politics and society, says William Cash

Ever since the days of Samuel Pepys in the mid-17th century (who began his ten year diary at his Westminster house in the wonderfully named Axe Yard, next to Downing Street) to Alan Clark in the 20th century, politician diarists have commented on how both Houses of Parliament resemble a strutting, thrusting, adrenaline and argument fuelled menage of a college or public school with its strutting peacock front benches, Establishment toads and prefects, loners and rebels, suck-up ‘Yes Men’ careerists, school bullies, drunks, and the usual useless nonentities – all lobby fodder for the Whips.

Within these factions of dandy cliques, cross-party dining clubs, All Party Select Committees and Party committees and ‘sets’ within the Westminster Club, is another club that MPs cannot be elected to, or curry political favour to enter though the green baize door. That is the elite club of distinguished author politicians (and a few rare novelists, aka Michael Dobbs, creator of the House of Cards trilogy) whose quality of books put them into an intellectual Garter club of usually no more than perhaps a dozen members per Parliament.

These literary MPs – whose books would be published regardless of whether they are MPs or not – are the All Souls of Parliament. And membership of this exclusive literary political salon – I don’t include journalists (including the new editor of the Evening Standard) however spiky or stylish or overpaid their prose – has little to do with quantity of words published. Despite his ten volume diaries, I don’t count the late Tony Benn as he was no stylist and his diaries were dictated.

Indeed, that is one reason why we founded the Spear’s Book Awards nearly a decade ago, with literary editor Christopher Silvester (editor of the Penguin Book of Parliament). Our awards have always featured a high number of books by politicians, from Sir Vince Cable to Jesse Norman (a member of the MP Authors’ Club). And, on the subject of the Spear’s Book Awards for 2017, I’m delighted to say that we will hopefully be announcing the date of our awards lunch and the shortlisted nominees with a new category – ‘Spear’s Political Book of the Year’ that reflects the drama of the recent political age.

We will be including political memoirs, biographies of MPs, political diaries, political histories – the entire Pepysian range of political writing and opinion. In previous years, our judges experience was that whilst there are many books – biographies, current affairs and memoirs – published by politicians of both houses, there are, alas, few good ones. Many seem written hastily (with ghost help) to hit the WH Smith stacks before Conference season; diaries written for the purposes of the serial rights financial motives; self-justifying polemics or re-cycled articles, speeches and think tank ramblings on the political margins.

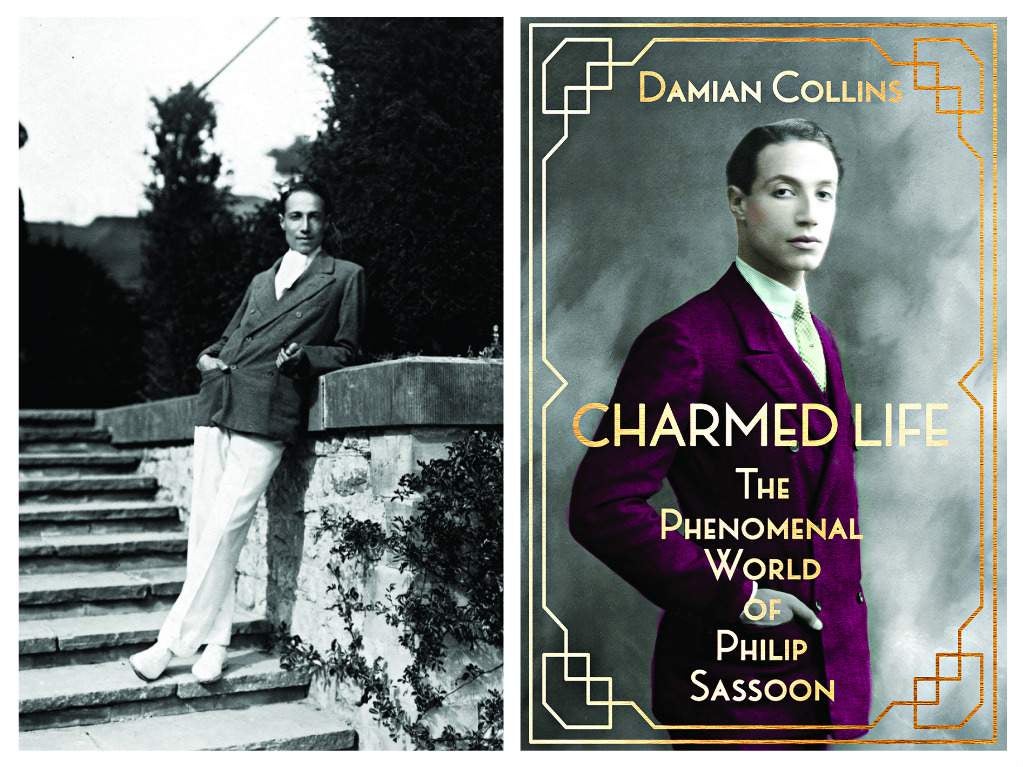

But over the Easter holiday, while in Norfolk, I was delighted to acknowledge the arrival of another true member of the Spear’s Parliamentary Distinguished Authors’ Club after reading Charmed Life, the Phenomenal World of Sir Philip Sassoon by Damian Collins, MP for Folkestone and Hythe, which after being published by HarperCollins to a chorus of good reviews has just been released in paperback. That Damian Collins happens to be the chairman of the Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sport comes as something of a relief. It is re-assuring to know that the MP elected by fellow members to lead the hugely important DCMS committee can not only write but has a fine cultural antenna and sweeping, almost Churchillian grasp of pre-war European and British politics.

While reading Modern History at Oxford University, Collins was tutored by historian Niall Ferguson which may have helped. The latter should be pretty happy with his history pupil. This sharply written biography is psychologically exhausting to read. Sassoon was elusive, exotic and socially and politically upwardly mobile on an oleaginous scale that infuriated many. But he rose – though his money, social connections and witty and metrosexual charm – to become one of the most prominent members of the pre-war British political and arts world establishment.

And what a subject Collins unearths without fear or favour. A super-wealthy member of a Jewish merchant family from the souks of Baghdad, his family had fled Iraq from Basra in 1928 with pearls sewn into their clothing. Sassoon was a cousin of the Rothschild family who played golf and was an intimate of the Prince of Wales, was secretary to General Haig through the carnage of the First World War (he spoke fluent French) and was personal secretary to Liberal Prime Minister David Lloyd George during the wartime coalition.

But a part of himself was troubled with self-loathing, or at least a large dollop of self-doubt. He was so unsure of himself and wary of admitting his Jewish trader roots that when he wrote an account of his journey (The Third Route) flying into the belly of Afghanistan and the Middle East as an air minister to monitor British imperial aerial power and air bases, he avoided all mention of him returning to his family’s humble souk trader Basra roots (they later when on to live like princes in Bombay and Paris). Air brushed out.

Sassoon knew everybody – from Charlie Chaplin to Charles Lindbergh, Churchill to George V and Queen Mary. If you thought that the most famous society and political hosts of the inter-war years were the likes of Emerald Cunard Rarely, Sybil Colefax, and Lady Desborough (the mother of his close friends Julian and Billy Grenfell who were killed in the First World War) then you will have to read this book to discover an even more exclusive society world that raised political and social entertaining to an art form.

Collins also casts perceptive parallels between today’s dramatic re-calibration of the political European order post the UK’s Brexit vote of 2016 – followed by Trump’s victory – and the events of the 1930s which saw the rise of popular fascism, a British political Establishment blinded by appeasement and a Europe unsure of itself.

This self-doubt was set against a lost world of political patronage with prime ministers ruling by house party and tennis court-style cabinet meetings that took place in the sumptuous settings of the lavish ‘At Home’ Cabinet lunches, dinners and house parties, and European political conferences held at Sassoon’s various luxury residences at Park Lane, Port Lympne in Kent (Sassoon was also MP for Folkestone and Hythe) and stately home of Trent Park outside London. Collins never really judges Sassoon. He leaves that to the reader.

To be honest there is quite a lot that is not to like about Sassoon’s almost compulsive-obsessive collecting of celebrities and politicians, socialites and artists. He didn’t just have an upwardly mobile party flitting nature. He gave dinners and lunches for prime ministers as a form of social and political pimping. He was accused by Chips Channon – a rival political gossip and royal host with a house in Belgrave Square – of dropping people like a rock once they lost high office. His politics were often off the flip-flop school.

But Collins manages to make Sassoon emerge as an all too human if hugely enigmatic man whose Jewish background and social, aesthetic and sexual complexities (he was discreetly gay) all make him such an unlikely figure to ‘epitomise’ (in the words of fellow MP Bob Boothby) ‘the sheer enjoyment’ of the decade 1925-1935, with life at Port Lympne, the exotic fantasy country house he had decorated by Rex Whistler, being one of ‘endless gaiety and enjoyment’.

Yet the problem with Sassoon, an outsider who always wanted to be accepted by the British social Establishment, was that one felt he never really enjoyed himself as much perhaps as his guests like Anthony Eden, Lloyd George or Churchill who used his stage set houses like personal hotels. He enjoyed the comment he once overheard from a guide saying that Port Lympne was ‘All old world style but every bit of it a sham’.

This applied to Sassoon as well. He was nothing less than a political Gatsby and Marcel Proust of Britain rolled into one between the wars. Collins follows Sassoon’s life and career like some Westminster Nick Carraway with the most interesting part coming at the end when we see Sassoon rightfully credited for his important role as air minister in ensuring that the RAF were not left behind Germany in the German-British air force arms race of the late 1930s.

What emerges is that Sassoon played a crucial role in helping Britain be prepared for aerial war with Germany. It was not just Churchill and the likes of civil servant turned industrial spy Ralph Wigram who ensured (and pre-warned ) that Britain had enough Spitfires built before the Battle of Britain of 1940 above the fields of Kent.

Collins has written a book of inscrutable and impeccable research. Much of the material is new, notably from the Cholmondeley family archives at Houghton Hall in Norfolk. Sassoon’s immensely wealthy heiress sister Sybil, became the Marchioness of Cholmondeley after marrying George, Earl of Rocksavage in 1913 at a 15 minute service in Victoria with no more than ten guests. Whether the marriage had anything to do with her money, Collins diplomatically doesn’t say.

Above all what struck me about the book is how the nature of political power and patronage has changed in Britain; or perhaps has only since Theresa May has come to Downing Street. In reading Charmed Life, one cannot help be reminded of how much the David Cameron Westminster era of titles and tennis parties, lavender favours and honours mirrored the same patronage and political social game as played by Sassoon. Old Etonian Sassoon would have been in his stride as a leading member of the Cameroon chumocracy of pals from Eton and Oxford who ruled with a 1930s style of entitlement.

It was Henry Fairlie, writing in The Spectator in 1955 – in the context of Anthony Eden – who nailed why Philip Sassoon was allowed to rise to the dizzy social and political heights of the British Establishment – despite the fact that privately many of the more aristocratic members thought Sassoon was overrated and no more than a wealthy political flaneur and gossip. Yet like him or loathe him, Sassoon gave the parties and political ‘Cabinet lunches’ that tout London- from Diana Cooper to Churchill – wanted to be invited to.

‘What I call the “Establishment” in this country is today more powerful than ever before,’ wrote Fairlie. ‘By the “Establishment” I do not mean only the centres of official power—though they are certainly part of it—but rather the whole matrix of official and social relations within which power is exercised. The exercise of power in Britain (more specifically, in England) cannot be understood unless it is recognised that it is exercised socially‘.

How right Henry Fairlie was in 1955. That was why Evelyn Waugh described ‘charm’ as one of the deadliest of English social sins. The English ‘disease’ no less, as the exotic old Etonian Anthony Blanche says to Charles Ryder in Brideshead. In many ways the gay socialite aesthete Blanche and Sassoon have much in common, including a taste for expensive suits tailored in the New York style.

Let’s just hope that with Theresa May and her new Conservative Party manifesto for June 8, the next government sweeps away the Cameron and Osborne era’s social ashes from the grate of Downing Street. Maybe it’s finally time for political power to be exercised by merit and hard work in a fair way for all – not just the gilded Etonian and Oxbridge few. Or the Blair years of Cool Britannia sofa government. Noel Coward called Sassoon ‘a phenomenon that would never recur’. Although I dare say I would not have had the moral or social courage to have tuned down his engraved At Home invitations, I do hope Coward is right.

Damian Collins MP will be writing the Diary for Spear’s in the next issue