As the world’s most controversial bank marks its 150th anniversary, David Dawkins speaks to some of its leading British alumni and assesses its influence around the world today

On 25 April, a woman was peeled from the road outside Goldman Sachs’ unmarked office on Fleet Street. ‘BOOBY TRAP,’ roared The Sun. ‘Eco-warrior glues BREASTS to the road in most bizarre stunt yet.’ But it didn’t quite make sense. The protester, part of the Extinction Rebellion disruption, was not formally protesting against the financial crisis, 1MDB or the gulf between the haves and the have-nots. And Goldman Sachs is not directly a carbon polluter or climate change denier.

Would gluing your breasts to the road outside Morgan Stanley, JP Morgan, RBS or Barclays have had the same effect? Probably not. But in 2019, the year of its 150th anniversary, Goldman is special like that.

Founded in 1869 in New York, Goldman wasn’t always such a totemic exemplar of the Financial World Order (and the hate that being so inspires). It was only in the Eighties and Nineties that it broke away from the pack. Today it has 30 offices around the world, more than 36,000 staff and $1.5 trillion in AuM and is quite the 21st-century behemoth. And, as at least one of the senior voices from the bank we spoke to makes clear, it’s tough at the top. With the success has come opprobrium.

Indeed, the idea of Goldman Sachs, the space it has come to occupy as the Bond villain business of the investment banking world, was created in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. In 2015 it came bottom in the yearly Harris Poll ranking of the 100 most visible companies in the US. Even BP (post-Deepwater Horizon) was higher in the list, leading Bloomberg to claim: ‘People hate Goldman Sachs more than oil spills.’ But it’s more than that.

For the public intellectual Nassim Nicholas Taleb, a former trader, risk analyst and the living collision point between Wall Street and philosophy, Goldman Sachs is part of a global 21st-century problem where hugely powerful bodies are insulated from the consequences of their actions. He tells Spear’s that the firm’s 1999 IPO saw it ‘switch to a corporation with no true skin in the game for their partners… the equivalent of warriors such as “General” Petraeus who have never seen a battlefield.’

While leaning further to the left, sensible socialist Leo Panitch believes the ‘revolving door’ relationship between Goldman Sachs and positions of political power is the key reason why so many people feel the firm is just too powerful.

Goldman is a part of how the US has shaped the world since the Seventies: ‘They’ve operated hand-in-glove in the informal empire,’ Panitch explains. ‘This is not an empire of the old kind that expands by conquering territory through military conquest and absorbing it as colonials. It is “informal”, in that American capital penetrates other states and becomes part of their domestic capital – with employees for those corporations really being citizens of another state.’

This is the relationship that’s taken first Sidney Weinberg (under Franklin D Roosevelt) and later Bob Rubin, Steven Friedman, Hank Paulson and Gary Gensler to the heart of government in Washington.

The tradition continues today in the Trump administration, with ex-Goldman figures Steve Bannon, Gary Cohn, Steve Mnuchin and Dina Powell. There’s little doubt that Goldman Sachs has left its mark on the world, and in doing so has become the global political punchbag for every form of financial wrongdoing.

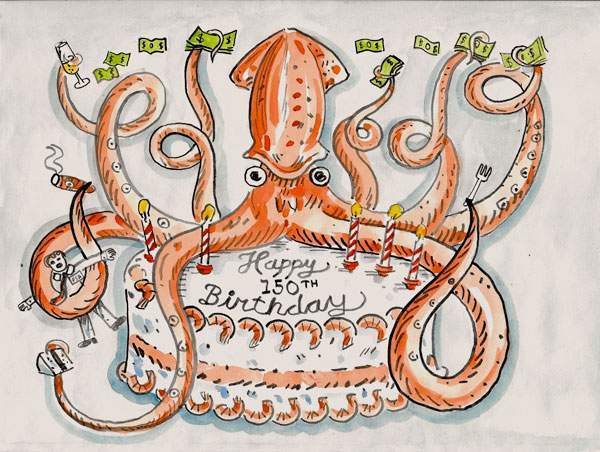

‘The world’s most powerful investment bank is a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity,’ wrote Matt Taibbi in Rolling Stone in 2009, ‘relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.’

The piece created a single idea of Goldman around the world: a patchwork quilt of money, power and collaboration. It was part fact, part conspiracy theory.

Yet, if you consider the financial price that ‘bulge bracket’ banks have paid since the crisis, you’ll see that Goldman was far from being the worst offender. CCP Research Foundation confirms that Goldman Sachs paid £10.71 billion in ‘conduct costs’ between 2012 and 2016 for ‘the financial consequences of bank misconduct’.

It’s a huge figure – but it was dwarfed by the costs forced upon Bank of America Corp (£45.59 billion), JP Morgan (£33.64 billion), Morgan Stanley (£24.36 billion) and RBS (£21.51 billion). In fact, CCP has Goldman Sachs down in the 11th place in the post-crisis naughty list.

Pointedly, Frank Partnoy, professor of law at the University of California Berkeley and a former derivatives structurer at Morgan Stanley, told CBS’s Anderson Cooper: ‘If we look back at Wall Street firms responsible for the crisis – the firms that in 2007 had these huge exposures to sub-prime mortgages – it’s not Goldman Sachs. If every bank had been like Goldman Sachs, we would not have had a financial crisis.’

The hand of Hank

Dan Awrey, professor of financial regulation at Oxford University, tells Spear’s there is no ‘empirical’ reason why the ‘level of animosity’ directed at Goldman would be higher than its peers. So where to start? Well, eyebrows were raised in 2008 when the US treasury secretary Henry ‘Hank’ Paulson, a former CEO of Goldman Sachs, signed off on the $85 billion bailout of the insurance giant AIG.

Goldman was immediately repaid the $13 billion it was owed by AIG, smoothed over following Goldman’s decision to become a bank holding company at the height of the crisis (and thus able to access liquidity support directly from the Federal Reserve).

Awrey notes that the Paulson-Goldman connection ‘aggravated the media/public’s sense that the game was rigged’. Then there have been plain PR blunders. Chief executive Lloyd Blankfein, says Awrey, threw the news media ‘a lot of meat’ when, in the immediate aftermath of the crisis, he claimed Goldman was ‘doing God’s work’.

Finally, when the US Securities and Exchange Commission filed a civil fraud suit against Goldman in 2010, accusing it of misselling $1 billion in toxic debt, The New York Times called it ‘one of the darkest chapters in the company’s 142- year history’. The company settled, agreeing to pay $550 million without admitting or denying guilt.

What it adds up to, according to Awrey, is ‘the sense that Goldman profited from the crisis – both in terms of its profitable short positions on various sub-prime assets and the fact that its market position was essentially strengthened by the crisis’.

As a result, the bank lives in the shadow of the controversies of the financial crisis – and this is also driving change at the firm. ‘Back in 1991,’ says Chris French, the London-based head of private wealth management EMEA, ‘we were told: you never speak to the press, you never tell anyone what we do, it’s secret. We don’t have our name on the door and we don’t exist. The financial crisis,’ he adds, ‘changed all that.’ French, who joined Goldman’s investment banking division in 1991, tells Spear’s the London arm established a reputation for trust and integrity during the ‘Big Bang’ era of deregulation under Margaret Thatcher.

‘The “white knight” [reputation] was something the M&A [team] was founded upon,’ he says. ‘We didn’t involve ourselves in the attack side of aggressive takeovers. As the global wave of M&A began we found a large number of companies wanted to appoint us as “anti-raid” defence advisers. We would go in and be there to defend them and not work against their interests.’

For fragile British firms, it no doubt felt good to have a noisy, sharp-toothed American pitbull barking in the garden during those testing times. Back in 1987, Goldman took on a massive loss as the US adviser in the privatisation of the UK government’s remaining interest in BP – at the time the largest sale ever by HM Treasury, and, it turned out, unfortunately timed alongside the ‘Black Monday’ stock market crash.

The move has come to be considered the high-point of Goldman’s ethics; John Weinberg described it at the time as ‘expensive and painful’. ‘But,’ he added, ‘we are going to do it’.

The next year the bank rolled up its sleeves in defence of British sweet giant Rowntree when it became the target of what was then the largest takeover battle in British corporate history. Among the British hires to Goldman in the Eighties was Guy Hands, now best known as the founder of Terra Firma Capital Partners, who joined the bank in 1982 and holds the distinction of being fixed income’s first grad hire.

He tells Spear’s that even in the early days Goldman was prepared to do things differently. ‘In 1982 we were the underdogs: profitable, but not big,’ he says. ‘It was the era of the “big swinging dicks”, but Goldman was seen as more sophisticated than that. Most of the City traders back then were East End barrow boys. Goldman wanted something very different.’

Around the same time, another future Goldman grandee, Jim O’Neill, noticed that something was up with the guys from Goldman.

He tells Spear’s: ‘I remember the first time I read something about the culture of Goldman Sachs in a magazine, in the late Eighties. I remember thinking, “What a weird place that is. I’m not sure I’d like to work there. Why do they all work so hard? Why are they all so self-absorbed?”’

O’Neill spent 19 years at Goldman Sachs as chief economist and then chairman of asset management, identifying and coining the term BRICs in 2001 and eventually being ennobled and joining the Cameron government in 2015. Today, he clearly remembers the bank’s partnership culture, the desire to get to the top and a meritocracy that allowed the best to progress.

Survival course

‘When I first met Lloyd [Blankfein], he said that there are two things about Goldman that you will find very different. One: the average level of capability of people there is probably much higher than you’re used to. Two: it is a very meritocratic place. And I thought, “Yeah, right.” But it was true. I was shocked, and intimidated by the number of remarkable and capable people. I thought, “How the hell am I going to survive this?”’

O’Neill is famous for being one of the few to be ‘brought in’ as a partner, but he believes the standard partnership track, as well as the firm’s overarching culture, created value for the client.

‘What they [clients] really loved about us is that that they knew that our ideas would be influencing Goldman’s own partner capital investments. I used to ask some of the most legendary investors out there, important clients of Goldman’s, “What is it about us you find so attractive?” And they said it’s because of the weird interplay between their own risk-taking and research [and] how you can get a feel for what Goldman is doing with its own capital.’

And that’s where Goldman was completely different, because it was the partners’ money.

‘Morgan Stanley in those days had a fairly good research department, but they didn’t actually bet on it like Goldman did,’ adds O’Neill.

Has that all-important culture survived the IPO of 1999 and decades since?

‘While it has managed to keep a lot of the culture alive, Goldman has found it more difficult to achieve this away from the centre,’ believes Hands. ‘Today, people who join Goldman Sachs don’t expect to be there for the rest of their lives; when I joined Goldman I never expected to leave. I would have loved to have stayed there all my life and become a partner – it was the most amazing place.’

Ransom notes

Senior voices who worked at the bank more recently than Hands insist it still is. Former Goldman partner Charlotte Ransom, who left to set up Netwealth, worked in its securities division for 15 years and then in private wealth for five.

She tells Spear’s that many of the partnership fundamentals are hale and hearty two decades on: ‘The partnership was still very relevant when I left at the end of 2011,’ says Ransom. ‘If you’re a partner, you have a fiefdom that you control.’

The Goldman Ransom talks of is an environment where productivity was rewarded, but never at the expense of ethics.

‘Pre-IPO the rate of growth was slower and the cultural fit was key for new hires – as well as playing a big role in promotions. As the firm began to grow more quickly, it’s likely to have been harder to keep that culture.’

Following a recent departure, one Goldman insider told Spear’s in no uncertain terms: ‘People who don’t display the hunger and ability to be successful don’t last here and that’s a fact. And that’s how it should be.’

With recent headlines in mind, I ask Ransom about Goldman’s partnership in relation to its perceived appetite for controversy. ‘It’s tough at the top,’ she admits. ‘Goldman has dominated so many different league tables for a very long time so it’s always a target, and I was very sorry to see the problems in Malaysia. In my experience, the business guardrails put up by Goldman are second to none, but when something happens people are very quick to be triumphant about the fact that Goldman has been caught out.’

It’s not the only controversy currently circling. Ransom also takes on an important question on gender issues at Goldman: ‘When I’m asked about being a female in finance, people raise their eyebrows when they hear that I was at Goldman and I’m happily married with four children. They can’t believe it,’ she says. ‘It says a lot about Goldman’s culture and the meritocracy. It was hugely satisfying to be rewarded for productivity and still be able to do the other things in my life that mattered to me.’

At its heart, the story of Goldman Sachs is one of a ruthless and brilliant business, a collision of investment culture with global opportunity as the world changed shape in the Seventies and Eighties. It is the kind of corporate melodrama to which people will often gravitate.

Why not? It’s a story of a business culture beset with genius, consequence, tragedy and farce. And, like many parts of the modern working world, it’s not always easy to understand what it is, how it got here and why it became so influential.

And sometimes what people don’t understand makes them angry – or afraid. In many ways, therefore, Goldman Sachs is deeply misunderstood. It is plainly not the monster it’s sometimes made out to be. Arguably it’s more labyrinth than minotaur – the territory, not the terror.

That, then, is the paradox at the heart of what is arguably the world’s most hated yet also its most successful bank. Perhaps, with Blankfein’s tenure now at an end and David Solomon taking the reins, it will start channelling some of that ambition and intensity of focus towards getting people to like it, rather than just making money for its clients and itself.

Then again, it might not. Either way, the world will be watching, and – dare I say? – be keeping abreast of the situation.

Timeline: Goldman through the years

Read more: