Could a change in our habits mean a comeback for dress watches? If so, it’s not before time

If office life will never be the same again, so too will the groaning, lugubrious business of trade shows and conferences – cash cows for those that host them, a deadly chore for those who attend.

That’s certainly the case in the luxury watch industry, whose linchpin fairs were already embroiled in a fight for survival and relevance before the pandemic tipped things into the abyss.

Baselworld, scheduled for April after two years of falling exhibitor numbers and growing resistance to its extravagant pricing and style, fluffed an attempt at postponement in March so badly that Rolex and Patek Philippe led a final walkout of big-name brands, announcing plans for a show of their own in Geneva next year.

That’ll coincide with the rebranded SIHH, now called ‘Watches & Wonders’ – though that event’s Covid-induced pivot to digital, with new watches from a host of brands announced via an online portal, worked well enough to call into question the necessity of the old, bloated festivals of luxe.

Zoom press conferences and digital downloads may not offer the same champagne-fuelled grandeur, but it’s certainly easier on the childcare.

Frankly, the idea of passing timepieces between hundreds of attendees is an icky thought just now.

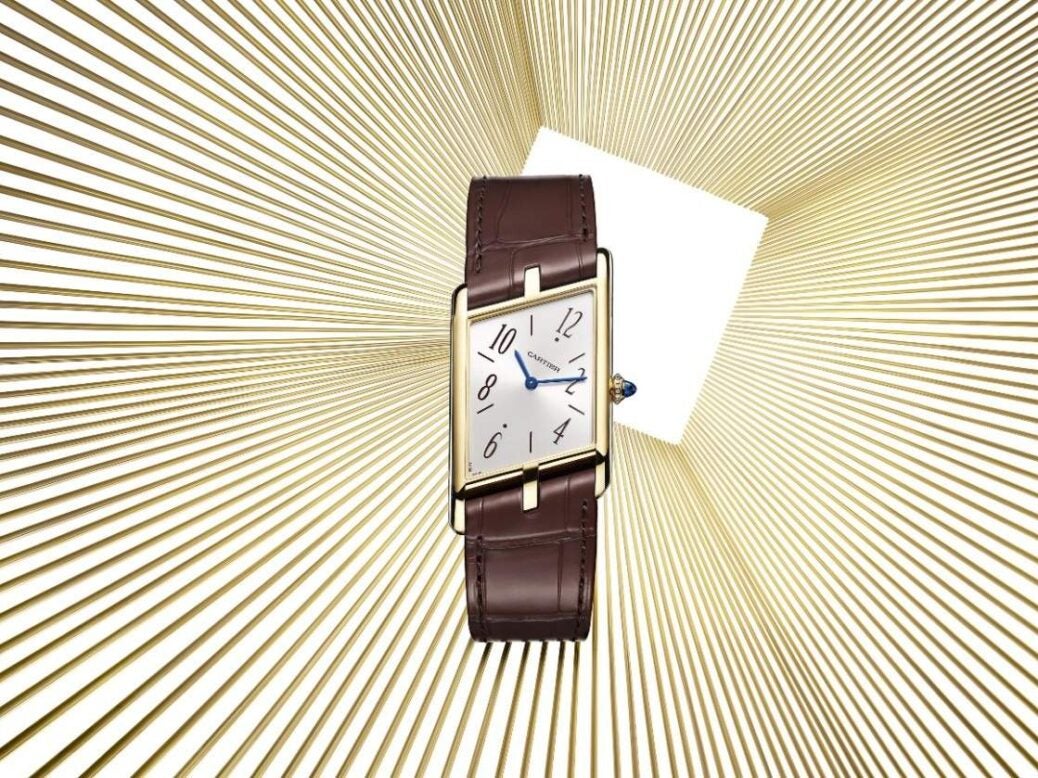

But it gets a bit less icky when confronted with something as lovely as the reborn Tank Asymétrique from Cartier, a 1930s design in which the traditional rectangular case is slanted jazzily into a parallelogram. This was easily my top pick from the Watches & Wonders launches, and it’s not simply the eccentric, historical brilliance of the design that I find alluring. It’s the fact that as a dress watch – a timepiece that’s simple, slim, elegant and formal – the Asymétrique is a fine advertisement for a genre that’s been fading towards obscurity.

Which is odd, really, given that the dress watch is really watchmaking in its purest form. It requires no increased robustness or novel materials, and no messing with added functionality and complications.

The best examples like the Asymétrique even forgo the distraction of a seconds hand. A dress watch is a discreet, delicate vessel of horological finesse, and as such was for years held up as the emblematic Swiss timepiece.

But who needs (or needed) a formal watch in informal, flexible-living, pre-Covid times? Fewer and fewer people, apparently. At Patek Philippe, for instance, the minimalist Calatrava – the round, gold dress watch par excellence, launched in the 1930s and generally seen as Patek’s flagship timepiece – has slipped far into the shadow of the fi rm’s steel sports watches.

Conservative brands like Chopard, A Lange & Sohne and Piaget have been scrambling to reinvent themselves for the WeWork, city-hopping generation, launching the kind of steel-cased, sports-luxe all-rounders they once abjured. Perhaps, post-Covid, the understated finesse of the dress watch might have a reborn purpose. I hope so, because if you know where to look there are still fine examples to be found.

Elite Status

One brand unexpectedly flying the flag for dress watches is Zenith, which is seen as a chronograph specialist. Zenith’s ‘Elite’ range, starting from a little under £5,000 in steel, has been neglected in recent years, but no more, with the introduction of ravishing new designs in January this year.

The rose gold Elite Classic, with a minimalist style given added gloss by a sunray guilloché that fans its way around the dial, could come straight from the 1950s, the golden era for dress watches. Omega is another company known principally for its sports watches, but my favourite piece in its current line-up may just be the slim, refined De Ville Trésor, one of its very few hand-wound watches.

You only need wind it every three days, and you still get the benefits of the technical innovations Omega deploys in its modern automatic movements, meaning superior precision, extreme anti-magnetism and stability. That arguably makes it the most advanced hand-wound movement around, but the crucial thing is elegance: a hand-wound movement is considerably thinner, and a slim, unobtrusive profile is crucial in dress watches.

The design is low-key but delightful, particularly in polished stainless steel (£5,220) with a blue dial imprinted with an unusual texture like the weave of a piece of canvas. Dress watches can seem austere, but this one’s almost breezy. Seiko would probably be the last name most people would associate with watchmaking’s most refined category, but then most people don’t know about Grand Seiko.

The luxury wing of the Japanese behemoth was founded 60 years ago, though it’s only recently begun promoting itself to a more global audience. A few years ago I visited its workshops at Morioka and found hand-skills and engineering craft that surpassed much of what’s found in Switzerland. Its approach is exceedingly, almost defiantly conservative, which is why the dress watch is the perfect expression of its remarkable watchmaking.

This year it’s brought out a new version of one of its original watches from 1960 – you can get it in polished titanium or platinum, but it’s in gloriously retro yellow gold that it really hits the mark. At 38mm, it’s a little smaller than the Zenith and Omega examples, powered by a gorgeously finished hand-wound movement that’s visible through the case-back.

It’s a model that demonstrates how a dress watch is as much defined by what isn’t there as what is – it’s about rigour, restraint and quiet excellence. Qualities, you’d hope, that never really go out of favour.

Main image: Cartier Tank Asymétrique

This piece first appeared in issue 75 of Spear’s, available now. Click here to buy a copy and subscribe

Read more

How superyachts can boost the global luxury property market

Patek Philippe returns with the ‘Ref 6007A Calatrava’

Why the Omega’s Calibre 321 is exciting watch purists