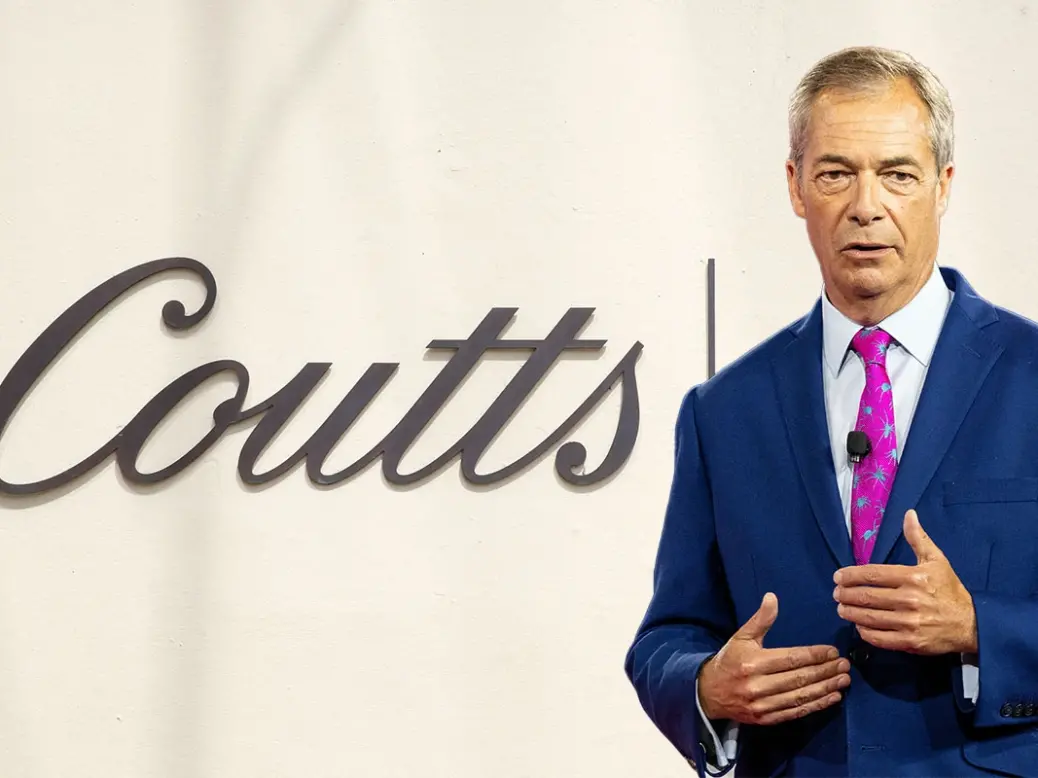

When it emerged that Coutts had ‘de-banked’ Nigel Farage last year, the headlines, column inches and debates on television and social media tended to focus on two things: the mechanics of the decision itself and, also, what it said about the dangers of ‘woke capitalism’.

The furore also cast some light, however, on something else: the way in which financial services companies assess high- profile or influential figures, through due diligence, know-your-customer (KYC) checks and other means. The aim of these checks, generally speaking, is to ensure that firms stay on the right side of legislation and regulation by avoiding the onboarding of fraudsters, terrorists and other undesirable would-be clients, such as oligarchs who have been subject to sanctions.

[See also: There are still lessons to be learned from the Coutts vs Farage debacle]

However, according to several experts who spoke with Spear’s, the current system is far from perfect. In part, this is due to its reliance on a number of databases and data-providers that are not always dependable. This reliance, the experts say, has led to some individuals being unfairly flagged as potential risks.

World-Check, PEPs and the problem with databases

Perhaps the most well known of these databases is World-Check, which is now part of the London Stock Exchange Group and describes itself in promotional materials as ‘an early warning system for hidden risk’. (The Dow Jones Watchlist and LexisNexis WorldCompliance are among other notable examples.)

Some 49 of the world’s 50 largest banks use World-Check to vet customers. The database holds details of more than four million individuals and organisations, including people who are ‘reported to be connected to sanctioned parties or… have been investigated for, or convicted of, financial crime, slavery or human abuse-related activities’. But a large proportion of the database is made up of ‘politically exposed persons’ (PEPs).

[See also: The best reputation managers 2024]

The Law Society defines a PEP as ‘someone who has been appointed by a community institution, an international body or a state (including the UK) to a high-profile position within the last 12 months’. According to leading litigation and crisis PR expert Lawrence Dore, this can include ‘politicians, ambassadors, office holders – anywhere where you might be exposed to potentially higher risks of corruption or influence’.

The definitions used to flag individuals have become increasingly broad, giving banks and other companies a reason to decline services to people who may have only a tangential connection to a PEP, who themselves are wholly legitimate figures. World-Check says it uses the Financial Action Task Force’s definition of what constitutes a PEP, ‘plus expanded definitions from the Wolfsberg Group, EU Money Laundering Directives, the USA PATRIOT Act and the World Bank. Country-specific PEP definitions are also considered.’

[See also: The reputation lawyers index 2024]

‘Secondary PEPs’ can also be flagged. According to Farrer & Co reputation lawyer Thomas Rudkin, being a family connection or associate of a PEP can be enough to land you on the list. ‘It is a bit unclear. There aren’t hard and fast rules beyond the fact that they say that once you are classified as a PEP, you’ll remain with that classification for a period,’ he says. Anti-money-laundering services provider SmartSearch says that ‘anyone who has been a PEP in the past might still qualify as a PEP years after they leave the high-profile position they occupied’.

The dangers of disinformation and misinformation

In addition, there are concerns about the accuracy of some of the information gathered by the databases and factored into decisions to classify people as PEPs.

‘The bulk of data is now coming from these media reports and online news, so that’s a huge pool of potentially inaccurate source data,’ says Schillings partner Juliet Young, who has more than two decades of experience in corporate intelligence.

[See also: Why HNWs must act now to fight the rise of disinformation]

It could even be ‘something as basic as a blogpost’, adds Phil Hartley, Young’s colleague at Schillings. ‘You have a lot of inaccurate or out-of-date information going into these, which leads someone to being classified in the first place.’

There’s also the threat of fake news sites which ‘mimic the mastheads of well-known publications’, according to Young, with dubious and shadowy sites churning out inaccurate information about high-profile figures and HNW clients. ‘Of the matters I’m dealing with, at least half relate to these kinds of issues, where inaccurate news or a smear campaign is driving some kind of judgement or categorisation that then needs to be rectified,’ she says.

The simple inclusion of a person’s name in data leaks, such as the Paradise Papers or the Panama Papers, can lead to inclusion on the database. But, Young notes, ‘not all leaked data pertains to high-risk individuals. There are lots of innocent businesspeople or private clients in that.’

[See also: The best reputation and privacy lawyers for high-net-worth individuals]

‘You can see how through no real fault of your own, you might end up on a World-Check list,’ says Lawrence Dore. What’s more, he adds, people aren’t notified about being added to a list, so might only find out when they’ve ‘suddenly got a problem with [their] banking’.

Some errors have been acknowledged, even if legal action has been required to get there. Last July the Telegraph reported that World-Check had paid a combined £190,000 in damages and costs to Turkish businessman Mehmet Baltaci after inaccurately flagging him as a terrorist. A High Court claim for libel was settled last April, with the embattled service removing the profile and agreeing not to republish the erroneous information.

For its part, World-Check says that ‘data is continuously assessed to ensure it remains up to date and we have multiple fields and secondary identifiers to minimise false positives with manual human fact checking and verification’.

While he believes the vast majority of people and organisations listed are ‘rightly on the database’, Rudkin says he has dealt with ‘tens of cases’ around potentially erroneous inclusions.

An online clean-up

So what can be done if you’re an HNW who has been unjustly flagged as a PEP? The legal approach, Rudkin says, is to ‘try and utilise a person’s rights or an institution’s rights to have information corrected or removed’. This can be done through engaging with databases to challenge inaccurate content and using the ‘right to be forgotten’ under UK GDPR rules to tackle the publication of old and inaccurate news articles. ‘If there’s adverse media that’s inaccurate, you can think about trying to get the information removed at source, so that it’s no longer available on the internet and therefore will no longer be pulled into databases like World-Check,’ Rudkin says.

As well as tackling the underlying press reports that are the fuel source for bad categorisations, Hartley says Schillings can also make ‘compliance packs’ to show banks a more rounded picture of their clients’ affairs – information that is carefully sourced and substantiated, rather than banks seeing ‘a partial, single media article’.

[See also: The best reputation managers for high-net-worth individuals]

From a comms perspective, Dore says HNWs must engage in regular online auditing to keep track of what’s being said about them, and ‘to take measures where there are inaccuracies to clean [them] up’.

‘Investigate what is being reported about you,’ adds Young. ‘Who is saying what about you? What allegations are being made? How are they being recycled? How old are they? Who’s publishing them? You have to sort of gather all that, first of all, so my piece of advice would be: know what’s out there and then build a strategy around that.’

This feature was first published in Spear’s Magazine Issue 90. Click here to subscribe