The accusations against Bradley Wiggins draw attention to lack of funding in the world’s doping agencies, writes Christopher Jackson

Walk out of Maida Vale tube and head north up Randolph Avenue towards Paddington Recreation Ground and you’ll find two blue plaques side by side.

The first commemorates Sir Roger Bannister and reminds you that the great athlete trained on the ground’s ‘cinder track’ in preparation for his famous dash on 6th May 1954 at Iffley Road. No one would question its fittingness: when Bannister died on 3rd March, he was fêted as an emblem of sporting purity. In being the first to run a mile in under four minutes, Bannister is in the category of those who, like Neil Armstrong, embody the human desire for betterment.

But he was also a reminder of something largely departed – the gentlemanly amateur. Bannister was more proud of the work he went on to do in research into the nervous system as an academic and doctor than he was of his historic run.

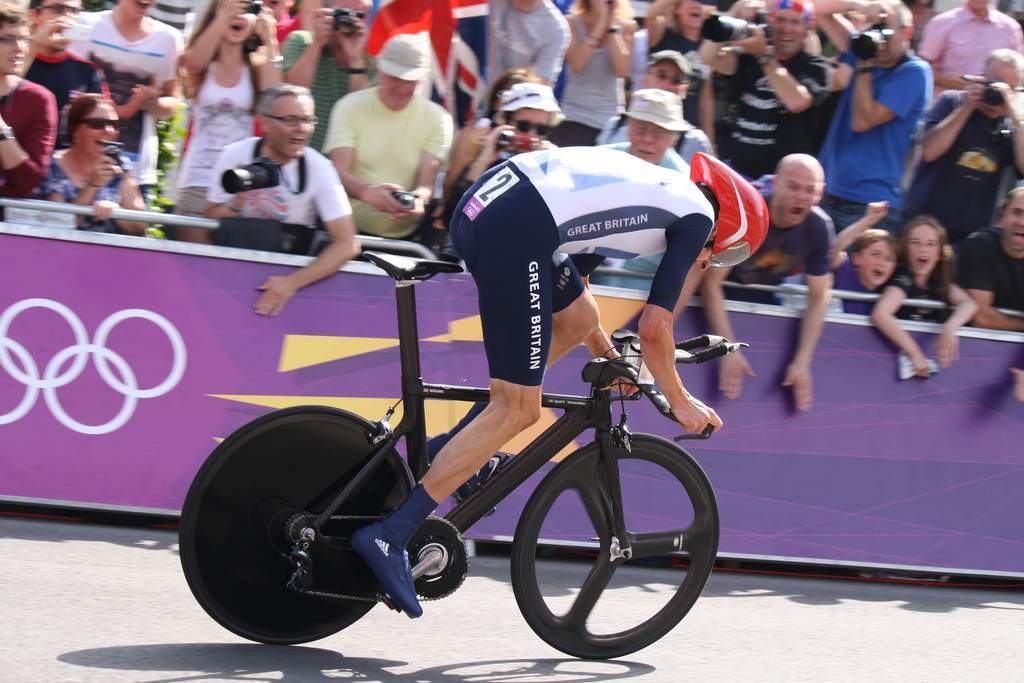

Which brings me to the other plaque in Paddington: this is to Sir Bradley Wiggins – although one wonders how long both the knighthood and the plaque itself shall endure. It states that Wiggins ‘enjoyed the facilities at Paddington Recreation Ground and lived close to the site attending nearby St Augustine’s CE High School’. It goes on to list the achievements we all know off by heart: first British Tour de France winner; first cyclist to win the Tour and an Olympic Gold Medal in the same year.

However, as we all know, things are changing rapidly. The report just published by the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee called ‘Combatting Doping in Sport’ is enough to make one wonder what has happened in the interval between the respective careers of the two greats. The answer is, of course, that money has entered sport to an extraordinary degree.

But first Wiggins’ current predicament. To see the man who defined the heady summer of 2012 answer questions on the BBC yesterday was to witness a man brought low. Wiggins now has that florid-eyed and worn look people have when they are facing trial by media. If we could talk to Kevin Spacey he’d have that same appearance: it is the image of someone once entirely confident now both humbled, and exhausted.

And the way the modern world works is apparently that the interviewer – who, one might speculate, may not be entirely perfect in his own life – delivers a series of flat and humourless questions, full of a grave foreboding which is itself a premature verdict. It is the intonation of likely guilt. One might add that the tone of a television interview is distinctly different from the open-ended cadences – the mood of free enquiry – of a court of law.

Wiggins’ demeanour, by turns baffled and furious, acted as a reminder of the need to extend pity. He is surely right to say that if he’d murdered someone he’d have been granted more rights than he has now: I may be underrating his acting ability, but his indignation suggests to me someone genuinely wronged.

Of course, there are still a lot of questions to answer. We do not yet know whether he abused his use of Therapeutic Use Exemptions at all; if he did, we don’t know how often. And he was certainly unwise not to talk about all this in his 2012 autobiography My Time. He was too busy creating a myth of the Mod-rocker-cyclist whose no-nonsense earthiness suggested impeccable values: he should have taken a leaf out of Obama’s Dreams from my Father with its cunningly pre-emptive admissions of youthful drug use. The media can’t sensationalise what they’re already meant to have known.

But vanity is not a criminal offence, and one fears we may be in danger of missing the real point. Wiggins is undeniably implicated in a set of structures that needs to change: indeed, it’s his misfortune to have become a totemic symbol of a flawed sport – and a celebrity who has emanated out of underfunded worldwide doping arrangements.

According to Cycling Weekly, since 2010, and throughout the period of implementation of austerity by successive Coalition and Conservative governments, The UK Anti-Doping Agency (UKAD)’s budget has fallen from £6.5 million in 2010 to £5.9 million in 2017. It’s true that the government has pledged to increase funding over the next few years: but at the moment it has one investigator covering 47 sports. The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) meanwhile must toil with a laughable pot of £30 million.

World sport has become an aspect of our televisual lives. With this comes great fame for the likes of Wiggins – and wealth too (Wiggins is worth about £13 million). We are a long way from finding out what was in the jiffy bag, and Wiggins has yet to know who his real accusers are. But it’s certain that without adequate financing, there will be these blurred lines – for a lack of people there to police them.

Roger Bannister is rightly loved because he never submitted to the corruption inherent in modern sport – in 1950s Britain that temptation didn’t exist. His life was rounded by the necessity to work in a way Wiggins’ is not. While we await the truth on Wiggins, he must be allowed to defend himself, and if the media cannot find it in themselves to suspend judgement, then readers need to drag the great principle of innocent-until-proven-guilty into that realm.

If Wiggins is guilty, he might be pardonably so – and more, the victim of a confusing system. If he is innocent, he is being cruelly wronged and undergoing, as he said, a ‘living hell’ for no good reason.

At such a time, it’s opportune to remind ourselves that a sport owes a duty to its viewers – but also to its competitors, no matter how gilded they become. As usual, that means money.

Christopher Jackson is deputy editor of Spear’s

Related articles

The £1.7 million Indian takeaway