Chinese money is covering the globe through high-value M&As — but the shadow of Brexit looms large over Anglo-Sino affairs, writes Max Johnson.

China has seen some of its biggest outbound M&A deals in 2016, with a huge increase in $1 billion-plus deals. Chinese companies, with access to cheap financing and government pressure to do deals, are on a global shopping spree to find growth opportunities, access new markets, find high-quality technology, and sometimes just bid the most to win — such as when Anbang bought New York’s Waldorf Astoria. This trend is no doubt set to continue. But how well is the UK positioned to capture some of this Chinese M&A activity? Very well, it turns out — all until 23 June came along.

The date of the shock vote to leave the European Union is now tattooed on the minds of financiers and fishermen alike. Deal-making involving British companies has sunk to its lowest level for the past twenty years — the corporate world is gripped in a state of fear over what to do. Will it or won’t it be Brexit? And if so, when? We are bombarded with daily news — some fact and some pure speculation. The same agencies that attacked Brexit are now split over how damaging the aftermath has been, with the Confederation of British Industry making positive noises while Standard & Poor’s calls any recovery a ‘mirage’. There have been other factors to spook investors as well, namely the US presidential election, French and German elections, terrorism, and eurozone growth (or lack thereof).

However, it’s not all bad. Some deals have been done against the Brexit headwind as corporates pursue opportunistic deals. As one Chinese proverb says, ‘In every crisis, there is opportunity’. Investor redemptions in open-ended retail funds are leading to fire sales of property assets being snapped up by the Chinese. The weak pound has led to other deals such as AMC Theatres — the US cinema chain owned by China’s richest man, Wang Jianlin — agreeing to buy Odeon & UCI Cinemas Group for £921 million. At the lower end of the spectrum, a Fujian-based chicken supplier offered £150 million for Splash Damage, a gaming company — a new spin on Angry Birds, perhaps?

Other countries are spotting the opening, too: South African retailer Steinhoff bought Poundland for £450 million, and News Corp acquired Wireless Group for £220 million.

Only one UK M&A deal is driven by optimism that Britain can make a success of Brexit — the £24 billion bid by Japan’s Softbank for ARM — and that deal by value alone accounts for more than a third of the value of all deals involving UK companies during the post-Brexit period (according to Thomson Reuters data). In other words, there haven’t been many ‘positive’ deals.

While corporate activity is struggling to find a way to be accretive, the politicians are not doing their bit to help encourage Chinese investment in the UK. Not only did Brexit cast doubt on the future of the economy, it also led to a complete overhaul of the UK political elite. David Cameron and George Osborne — so keenly focused on boosting the UK-China trading relationship during their reign — have been cast aside and, in Cameron’s case, have given up altogether. This has spelled trouble for the deals they have inked, such as the Hinkley Point nuclear project. Just hours after EDF’s board approved the £18 billion scheme, the new government pulled the handbrake on the deal, umming and ahhing to China that it was looking at it ‘closely’.

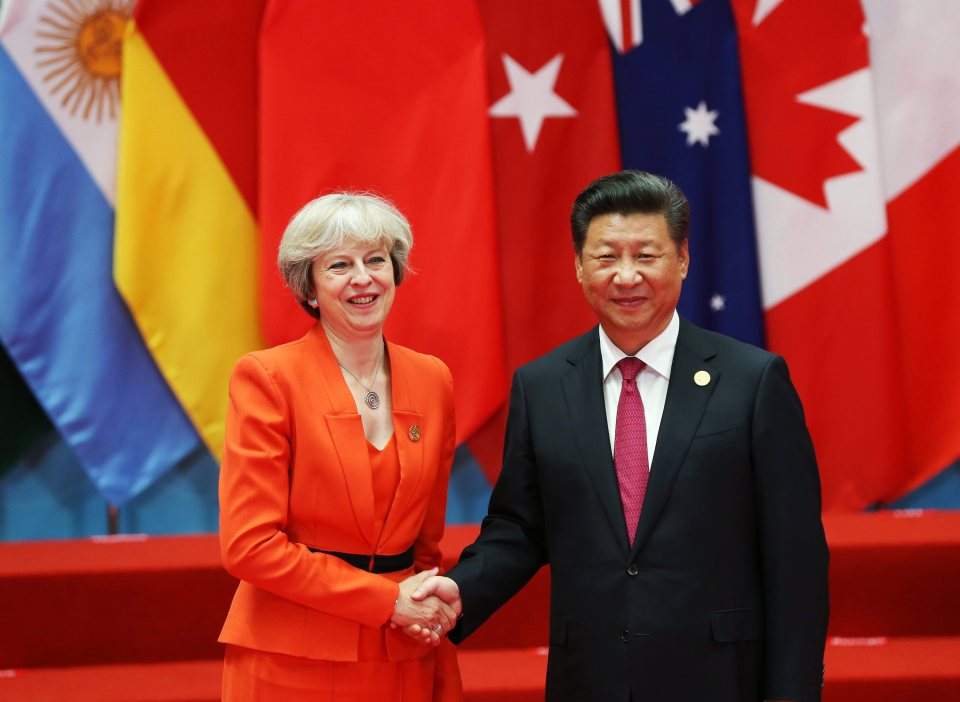

Theresa May in the end had little option but to sign off on it. Many on the UK, French and Chinese sides were calling for the deal to be waved through using some very colourful language. China’s ambassador to UK said: ‘Right now, the China-UK relationship is at a crucial historical juncture… I hope the UK will keep its door open to China and that the British government will continue to support Hinkley Point.’ In other words, screw us over on this and you can forget any more trade deals. It was throwing down the gauntlet in no uncertain terms.

To change now would have sent the signal to the Chinese that whatever they agreed with one government could quite easily be reversed by the next. It would have irreparably sent the relationship back into the ice age. No one wanted to go back to the frostiest of relationships that started when Gordon Brown met the Dalai Lama. Approve Hinkley Point, they said. So it got the green light as expected.

I suspect we could have called China’s bluff. There is a lot of evidence that Hinkley Point is not that important at all to the relationship. Here was a simple case of a new government faced with a transaction to take over a British company on quite unfavourable commercial terms. In recent years there has been some hostility to foreign takeovers, such as Pfizer/AstraZeneca or Kraft/Cadbury. Hinkley Point could still have been shelved and in time China would understand.

Having at first wanted to appear diligent and then approving it without any changes, the PM has added an even greater sense of political uncertainty to the already cloudy economic picture. More importantly, she may also have given the go-ahead to a bad deal for Britain. Was she really just reviewing the deal? And if so, as home secretary when it was signed, why had she not already studied it closely during Cameron’s premiership? Deep down it seems like she disapproved but had no choice in the end. We are in no position to negotiate — it is a £18 billion investment, the cancellation of which would have led to a £2 billion claim from EDF. Her advisers realised that.

The seeming show of strength has also revealed the weakness at the heart of how the UK government is run and decisions on deals like this are made. All the evidence is pointing towards this becoming a disaster: by the time Hinkley Point C even opens in the late 2020s there will be a host of cheaper technologies available, while the taxpayer will ultimately have to pay heavy subsidies into the second half of the 21st century. When asked whether Hinkley Point was central to the UK-China relationship, a government aide brushed it off and pointed out that the Chinese had bought Aston Villa FC, among other investments — hardly a direct comparison. Of course it’s central to the relationship.

Now that the UK government’s underlying position on Chinese investment is clear — we can’t do without it — there is admittedly one less barrier to deal activity ramping up. One can expect further ‘bilateral’ trade deals between the UK and China and UK and Chinese companies — as so much of Chinese M&A is government-led or at least sanctioned. But these are not necessarily ‘good’ deals and they need to be scrutinised more carefully.

True strategic M&A won’t return because political uncertainty is set to continue. In the meantime, so will the bargain hunters swooping like vultures, the overseas governments sensing the UK’s desperation for friends and free trade agreements, and the EU bureaucrats determined to make any divorce proceedings as costly and unpleasant as possible. It is hard to see which way the UK can turn. One solution the world is waiting for – trigger Article 50.

As on old Chinese proverb says, ‘flies never visit an egg which has no cracks’. It’s time to break the egg.