An exhibition in its last weeks at the British Museum tells of the falling short of an ideal, writes Christopher Jackson

America: we think we know it. Its enormity can seem offset by a certain transparency, arising from an easily digestible culture. It’s not a difficult thing to follow a Martin Scorsese film, or to sing along to Bob Dylan, Nobel Laureated though he is. Even America’s high art observes this egalitarian spirit: one thinks of Saul Bellow’s street smarts; Kubrick’s preparedness to plunder the novels of Stephen King; and Charles Ives’ symphonies, for all their polytonality, include references to town bands and parlour ballads – the everyday sounds of America.

It is also a country built on a comprehensible ideal of universal happiness. This is both its strength, and its vulnerability: its idealism persists, and drives it forward into entrepreneurial and cultural endeavour, but it is also a country continually falling short of what it would like to be. This exhibition is an admission of that underlying complexity.

The Founding Fathers, with their genteel notions of human nature, never guessed that their country could become as raucous as it has. The first exhibit here is Andy Warhol’s technicolour Electric Chair series from 1964. Each chair is vacant, but is no doubt awaiting its next occupant: it is a vivid reminder of the brutal efficiency of the state machinery required to enforce the death penalty system. Right from the offing then, this is no utopia. But as you wend this decades-straddling exhibition, Martin Luther King’s famous ‘I Have a Dream’ speech can be heard, insisting that the country is perfectible. With matching insistence, each room then reveals the numerous ways in which American reality is doggedly post-lapsarian.

Here then are Roy Lichtenstein’s cartoonish satires of advertising, reminding us how the high-minded American enterprise descended into a commercial one. In Jim Dine’s Self-Portrait in Zinc and Acid (1964), the artist’s body is absent, and replaced by a stand-in dressing-gown: in America, you become what you wear, diminished into a style or a commodity. These artists are arguably bound up in the historical moment. But Jasper Johns manages to transcend it with images of playful beauty: his lithograph Coathanger I (1960), for instance, disappears into a rainy background of grey, suspended sadly on its own – an object of human ingenuity nevertheless subject to natural processes. His famous Flag series is both a painted flag and a painting of a flag: it is essentially ambiguous about the patriotic impulse.

But these rooms also show the difficulty of describing a country so vital, amorphous and rowdy. In 0 through 9 (1960), Johns looks beyond the American question towards the meaning of number, and by association, the question of infinity. Others found consolation in general ideas: this wish to escape from a country too big to comprehend can also be found in the minimalists and conceptualists – represented here by Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt, among others. In these works we might just as well be in Europe, or Japan: abstraction, like thought itself, does not observe borders.

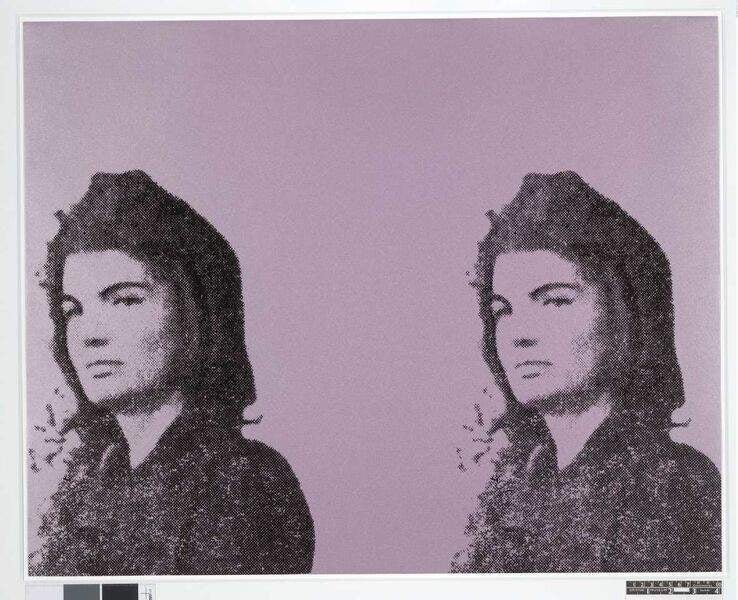

In the end, America is too rambunctious to be at peace in. As the century drew on, televised politics kept bursting in on the artist’s calm, entering the personal sphere. Americans have an unusually intimate relationship with their presidents: under their system, executive power and symbolic power is invested in the same individual. Here we have two Warhols: Jackie Kennedy, circa 1965, alone and JFK-less; and Richard Nixon – until Donald Trump, America’s readiest symbol of presidential corruption – with a Joker-style rictus. These leaders were not remote: they had rushed into the American home.

As the exhibition reaches its end, disenfranchised groups assert themselves. The AIDS epidemic is referenced by Eric Avery’s woodcut 1984 AIDS (2010) – based on a 17th century French skull which used to be placed on the door of plague victims. This commemorates the rage that the LGBT community still feel about the right’s response to that epidemic. In another room, women fight for equality, and a profounder recognition of their talents – a struggle satirised by Louise Bourgeois in her witty Ste Sebastienne (1992). Meanwhile, the black population remind us that Dr. King’s dream had not yet been actualised: in Emma Amos’s Stars and Stripes (1995), a scene of slavery ironically dominates the centre of the American flag.

It is left unsaid – indeed, it hardly needs explaining – that all these groups experienced gains under the Obama presidency. The Lily Leadbetter Fair Pay legislation – one of Obama’s first acts as president – enshrined the importance of equal pay in America’s statute books. Both Obamacare and the 2009 Recovery Act were designed to help the poor. The repeal of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, as well as the president’s support for gay marriage, dignified and advanced the plight of LGBTQs. One might even say that Obama, in his heterogeneous origins, and good-natured largeness-of-soul, was for many a fulfilment in his own right.

In the age of Trump, this could have been a melancholy show. But there is also reason for optimism here: in the roiling inspiration of a country that didn’t need to be made great again, since it was great – though flawed – from the start.

The American Dream: pop to the present, sponsored by Morgan Stanley, runs until 18 June at the British Museum

Christopher Jackson is head of Research at Spear’s