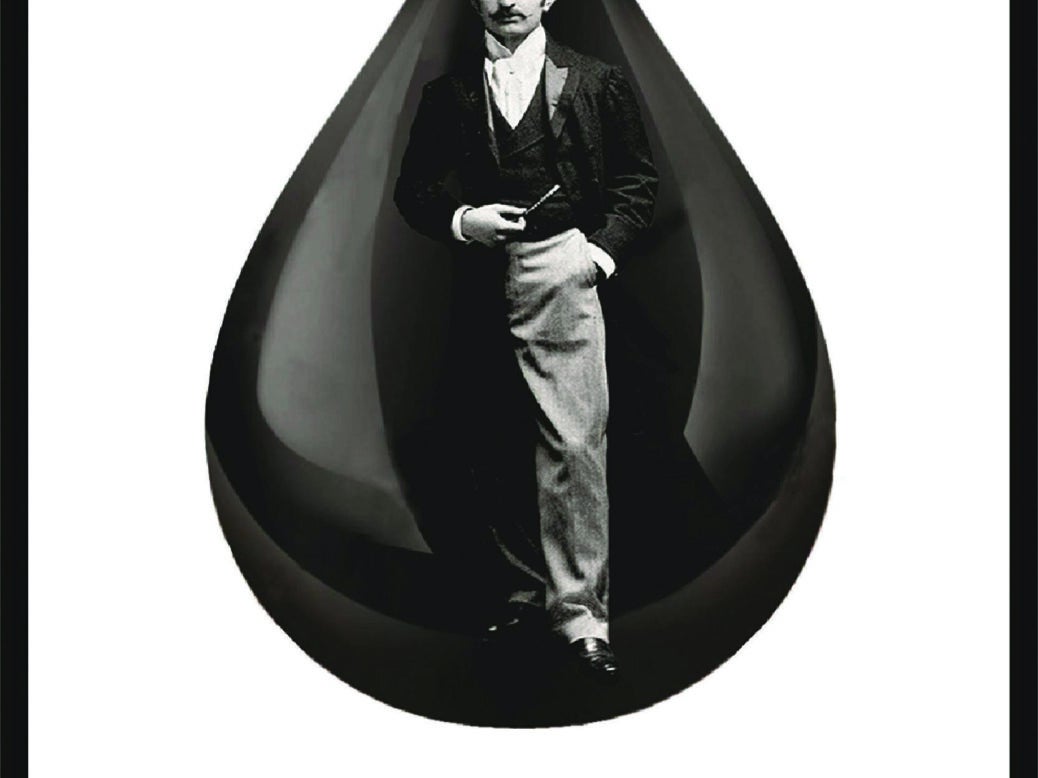

Emelia Hamilton-Russell reviews labyrinthine tale following the life of oil baron Calouste Gulbenkian

Mr Five Per Cent: The many lives of Calouste Gulbenkian by Jonathan Conlin

Niall Ferguson, when asked in an interview for the last issue of Spear’s whether wealth corrupts people, answered: ‘No, but it corrupts their children.’ What Ferguson also said – although this wasn’t quoted in the interview – is that sometimes the sort of person who eventually becomes super-rich is corrupt from the beginning.

The life of Calouste Gulbenkian, who owned 5 per cent of the world’s oil shares, proves Ferguson’s point on both counts. Gulbenkian accomplished much in his 86 years. The first man to exploit oil in Iraq, he was a shrewd businessman, and when he died in 1955 his wealth (equivalent to £5 billion in today’s money) and his art collection were unparalleled.

The son of a wealthy Armenian merchant in Istanbul, he brokered high-stakes oil deals for half a century, concealing his mysterious web of business interests and contacts within a labyrinth of Asian and European cartels, and convinced governments and oil barons alike of his impartiality. He styled himself as an ‘honest broker’ and, as Jonathan Conlin remarks, it was this ‘talent for evading attribution to this or that side’ that made him the most prolific dealmaker of his generation.

A ‘citizen of nowhere’, Gulbenkian was born in Turkey, educated in England at Harrow, lived in France and died in Portugal. However, none of these countries made much of an impression, and his loyalty to his Armenian roots was lacklustre.

Conlin notes: ‘Empires and states, diplomats and statesmen, spheres of influence… all were distractions to Gulbenkian: to be ignored if possible, or else coached and co-opted.’ As his wealth grew, he bought and renovated mansions in Paris and London, filling them with Rodin sculptures, Lalique glassware and Edward Burne-Jones paintings, but he did not live in them, preferring the anonymity of hotels.

Loyal only to himself, Gulbenkian’s interests were decidedly narrow: the acquisition of money, art and later – under doctor’s orders – sex. He is often described by Conlin as ‘inscrutable’, but his narrowmindedness also renders him so one-dimensional that he makes an unlikely, and unlikeable, protagonist even of his own life. When he died, his memorial service in Kensington’s Armenian church was so poorly attended that the newspapers deemed the sparse list of names too embarrassing to print.

As one British civil servant in 1942 summed him up: ‘Calouste is one of the richest men in the world… He is much concerned to avoid taxation… He is a great picture collector… There is a dossier for him I find, but there is little about him in it.’

Old habits

However, while Conlin’s unprecedented access to Gulbenkian’s estate archives has demystified the elusive ‘Mr Five Per Cent’, the descriptions of complex deals and intricate webs of contacts and alliances make for dry reading to the uninitiated. It’s the details of Gulbenkian’s eccentric habits (his pet canaries sipped exclusively on Evian water during the austerity of First World War Paris, for example) and chaotic private life that make the history lesson, and the necessity of keeping company with a somewhat dull man, worthwhile.

Today, the public-minded tech tycoons have overtaken the oilmen in the collective imagination, but the concerns of the wealthiest 1 per cent haven’t changed much in the past century. Tax is cast in the role of evil antagonist, to be avoided or evaded where possible.

Socialism was abhorrent to Gulbenkian, and as he wrote sometime before 1914, he believed ‘the trend for taxation plainly points to vicious attacks by political parties upon one section of the community, in order to catch the votes of the other and larger section’. Wayward children who refuse to earn their own living (or perhaps are incapable of it) are also a well-known blight on the super-rich.

Gulbenkian was no exception. He had a hedonistic, dilettante son, Nadir, a bohemian, free-loving daughter, Rita, who went on to publish a book of poetry, and a powerless, handwringing wife, Nevarte, who (although this is never made explicit) surely grew to loathe her husband.

Wracked with guilt over her perceived mal-parenting, Nevarte wrote a letter to her son on his 40th birthday, saying: ‘I feel terribly guilty for the hopeless way we have brought you up – our misguided love and appalling weakness have made you… a man with no responsibility – no ideal – no aim – tired of himself and tired of others – no wish for any respect – material comfort at any cost and with the minimum of effort to yourself seems to be your motto – I am terribly unhappy!’

Bad seed

Nadir – a chip off the old block in some ways – was unmoved by his mother’s distress, and even went as far as to take his father to court in response to a curtailed allowance. In an effort to mediate a particularly dire moment of family breakdown, Gulbenkian’s daughter demanded everyone write a list of their greatest wishes.

Gulbenkian’s were: ‘That no one want any money,’ and ‘If boyfriends must be had [by his wife or married daughter] then let them not a) want jobs b) want to sell antiques c) want to borrow money.’ The repeated reference to people asking for money makes it clear where his priority lay.

Gulbenkian guarded the ‘fortress’ of his fortune jealously, and the infamous 5 per cent would remain his until the end. Gulbenkian’s will is revealing in this regard. His son and daughter received half the estate under various conditions, and a relatively small amount (£5,000, or £2.7 million in today’s money) was sent back to fund Armenian hospitals and orphanages.

The remainder – a much larger cut – was to be given to the Palace of Versailles, with instructions to spend it so as to encourage ‘beautiful singing birds… to choose the park as their abode’. As Conlin points out, in a rare moment of sly judgement, ‘The bequest would have filled a lot of bird baths with Evian.’

Today, the companies that Gulbenkian created – including Shell and Total – are household names, while the international agreements he brokered still shape the fortunes of Iraq, Venezuela and other oil-producing countries across the globe.

But Gulbenkian never perused fame, indeed, to the extent that it didn’t affect his ability to accrue wealth, he couldn’t care less about his reputation. He only ever wanted fortune. Therefore, we feel little pity when it turned out that fortune, judging by his miserable family life and poorly attended funeral, was all he got.

Emelia Hamilton-Russell writes for Spear’s