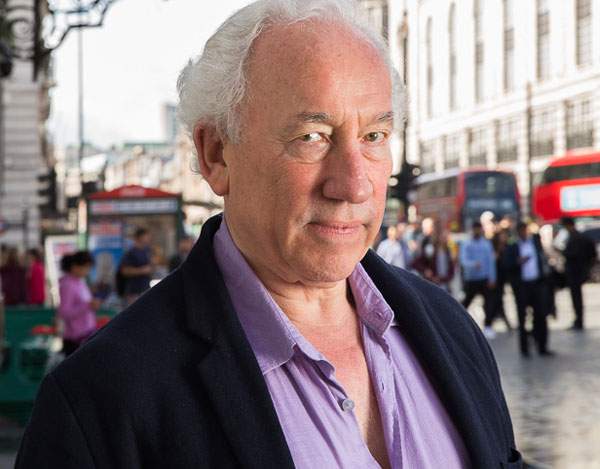

After a lifetime in the West End, actor Simon Callow has made his own tribute to it. On a stroll through theatreland with Arun Kakar he hails the surviving citadels

Simon Callow can recall his first experience of the theatre as seeing a production of A Christmas Carol as a young boy that ‘scared the shit’ out of him. His obsession with the stage, however, came a few years later when he saw Peter Pan in the now-defunct Scala Theatre between Charlotte Street and Tottenham Court Road.

‘It was snowing, my uncle took me to see it, and I just cried and cried,’ he recounts. ‘I was still crying, and then suddenly the lights went down and the curtain was lifted, and then we were in the nursery of the Darling family with the dog padding about. I just thought it was miraculous, and when they started to fly…’ His baritone trails off and he gestures dramatically to the sky.

Callow has written more than ten books and has well over 100 screen credits, from Amadeus to Four Weddings and a Funeral, but it is the stage that he calls his natural habitat. ‘I always feel comfortable in a theatre,’ he tells Spear’s over coffee in Soho. ‘However difficult the production might be or however difficult the people are on the night, I basically feel like I am at home.’

He evokes what one of his heroes, the poet and play-wright Jean Cocteau, described as a ‘red and gold sickness’ to articulate the feeling that took over him after seeing Peter Pan. ‘I was infected at a very early age and I haven’t really managed to kick the habit,’ he says with a warm grin. Life as a ‘theatre trainspotter’ ensued, and a hobby became a profession when Callow wrote a fan letter to Laurence Olivier and ended up with a job at the box office of the National Theatre at the Old Vic, where Olivier was director.

‘It was of course a revelation,’ he says. ‘If you’ve never gone onstage, you don’t really know what happens.’ Olivier had installed a canteen at the theatre – the first to do so – and the result was a melting pot for everyone involved, from ushers to make-up artists. Frequent diners included stars Maggie Smith and Ralph Richardson, as well as up-and- coming ‘kids’ such as Michael Gambon and Derek Jacobi.

‘We were all part of this big event,’ he says. ‘[Olivier] would make a point of sitting at the table with people he didn’t normally meet in his daily life, so it was a little awkward.’ Callow chuckles. ‘He didn’t quite know what to say – he was on this rather Olympic scale but was sweet and charming and connected to you, and that was very important.’

We set off through a blustery Golden Square on a whistle- stop tour of the West End, where Callow is showing me some of his favourite West End theatres. He and photographer Derry Moore have compiled a selection of 28 ‘great theatres’ from across the capital, and we’re heading to Piccadilly Circus and the Criterion, which opened in 1874.

I ask him what he makes of the modern West End, which many decry as a touristic husk of its former self. ‘It’s a commercial marketplace, but what do you expect? People who moan about there being too many musicals need to look at the guides of the 1920s. There was nothing but musicals!’ Sadly, he concedes, it is shockingly expensive. ‘I very well remember in the Seventies, there was a production of Gone with the Wind and they announced a new top ticket price of £5. Everyone said, “That’s it, the West End is finished, nobody can afford to pay £5.”’

Nowadays it’s tough to find a ticket for £100 – and the interval ice creams aren’t cheap either. ‘People pay an awful lot,’ he laments as we saunter through thickets of crowds. Callow writes fondly of the Criterion in his book as ‘one of the most uncommon and delightful playhouses in town’. We peek into the restaurant next door – the theatre’s former bar area – to admire what is left of the mosaics on the ceiling.

Former music hall the London Pavilion brims with frantic shoppers carrying plastic bags and smartphones. From this vantage point, Callow points towards Leicester Square and the Hippodrome (now a casino). ‘It’s all a graveyard of great theatres, this area,’ he sighs.

This triggers a thought in him. ‘Television and cinema came along in the Fifties, but the soul of theatreland has proven resilient,’ he says. ‘Theatre just turned around. It’s a lot to do with Andrew Lloyd Webber because he was English but world-class, and suddenly his shows were being done all over the world.’ There’s also something uniquely special about the experience of the theatre. ‘It’s the fact that you, as a member of the audience, affect the event,’ he gasps. ‘The audience changes the show and the show changes the audience. That doesn’t happen in the cinema; it can’t happen in the cinema. The social event is a great thing, the people all there together.’

We reach a packed Shaftesbury Avenue and slowly navigate our way over to the Lyric and the Apollo. The former, in Callow’s mind, is ‘rather severe’, but the Apollo, built in 1901 by non-alcoholic beer brewer Henry Lowenfeld, is ‘voluptuous and seductive’. Callow salutes it as the ‘most decorated’ theatre in London, a living example of how people who have nothing to do with the theatre fall in love with it. He gestures towards the Apollo’s elegant turrets and opulent detailing in a Louis XIV style. ‘Sometimes these people make terrible mistakes,’ he tells me. ‘I don’t think he made a terrible mistake, just a very beautiful theatre.’

We continue down Shaftesbury Avenue, where the Palace awaits. When I ask Callow who he thinks are the best performers around today, he answers almost without hesitation. ‘Last night I had a chat with Benedict Cumberbatch and I do think Benedict is an utterly extraordinary actor, very remarkable and very original and very distinct. Quite unlike anybody else who has ever been before him.’

He strokes his chin as we cross the road: ‘I suppose the most original actor of our times is Mark Rylance, who completely filters everything through his unique personality, his unique physicality… A real one off, Mark is.’ Then there is Maggie Smith, whom he considers to be the ‘greatest living actor of our times’. ‘I’ve acted with her, I’ve directed her, I know her quite well in that way,’ he says admiringly.

Royal appointment

We arrive at the Palace Theatre, where Harry Potter fans of all ages are flocking into the matinee of The Cursed Child. Callow has affectionate memories of the Palace, both as a theatregoer and an actor, having starred there in Lloyd Webber’s Woman in White in 2004.

Callow recalls seeing an ‘unbelievable performance’ from Judi Dench in a production of Cabaret here in 1967. ‘There will never be a better Sally Bowles ever: Liza Minnelli, eat your heart out!’ he exclaims. ‘She is nowhere near the character. In fact they changed the character to accommodate Liza Minnelli, but the character, the English convent- educated girl who goes to Berlin and throws herself at everything that’s going and just tries to make a living as a talentless singer… Judi just did that so utterly brilliantly.’

He muses on the strange history of the Palace, which opened in 1891 as the Royal English Opera House. ‘It was built as an opera house, it failed, it became a music hall, and then the music hall began to date and then it became a review hall, and then basically a musical theatre,’ he says, motioning towards its façade, a remarkably pristine array of pink-red brickwork. There are a few fans looking for selfies outside the theatre, and after Callow obliges them we stroll down Charing Cross Road and I glimpse at the Garrick, which sits on the corner opposite the National Portrait Gallery in a ‘sort of bijou theatrical Mount Rushmore’, Callow writes in the book. We slip by St Martin’s Court to the Duke of York’s Theatre, which opened in 1892.

What makes a great theatre? For Callow they are ‘ante-rooms of the imagination’, a place where a visitor can ‘shed the day and all its pressures’. At its best, it’s hard to beat. ‘You go into this space that is not magical – it doesn’t have to be escapist in every sense – but it has to engage your imagination and that’s what it is, it’s a sort of gymnasium of the imagination,’ he says breathlessly. ‘If you see it that way, then you’ll benefit from it in that way.’ And with that and a quick handshake, our walk reaches its end.

London’s Great Theatres, by Simon Callow and Derry Moore and published by Prestel, is out now

Illustration by Adam Dant

Photography by David Harrison

Read more