Great Walls

An apartment in China is like a Patek Philippe watch: you never really own one. But that’s doing nothing to slow down the mad rush for prime real estate, says Harry Dean

IN CHINA THERE is a saying: ‘If you have money, you can make the Devil push your grindstone.’ What this means for luxury property is that no style, no location, no taste, however idiosyncratic or opulent, is out of reach.

As China continues to grow fiercely, its number of millionaires and billionaires grows with it. Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, as well as a host of other second- and third-tier cities, are barely recognisable from their former states. Immaculately swept streets lined with pristine hedges run criss-cross around imposing skyscrapers. Offices, luxury apartments, villas, French-style châteaux, Imperial courtyards and underground empires — there is little that cannot be built in China and nothing that someone cannot afford.

There are now 271 billionaires in China — and rising — according to the Hurun Rich List 2011; if undeclared wealth were counted, there may well be more than 600. With such accumulations of wealth there have to be outlets. Family is of paramount importance in Confucian philosophy, and the number of Chinese children being sent abroad to study is at a record high. The next things they buy are luxury goods — polo ponies, fast cars, fine wine, cigars, fashion brands, yachts… (It is ironic that a lot of fake merchandise comes from China to be sold in the West but what the Chinese want to buy are our genuine products.)

But the new investment and luxury spending category is property. Let me be clear: property in China is owned by the state but private residents can obtain a 70-year lease. When that expires there is usually some renegotiation and revaluation of the property. Ownership here is the equivalent of the UK’s leasehold.

Prices are going through the roof everywhere, not just in Beijing and Shanghai. Figures from the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics in Shanghai Daily showed that ‘all 70 cities monitored… saw prices of new homes rise from a year earlier, with 25 reporting increases of five per cent or more’. The Chinese government has revealed its fear of the property market overheating with the imposition of various measures, including interest-rate rises and a property tax in Shanghai and Chongqing.

Knight Frank, which carries a stamp of Western reputability which appeals to Chinese in the luxury market, is advertising several houses for £5 million, although the supply seems limited. China’s ‘most expensive personal residence’ — a ‘bell-towered monstrosity’ in Shanghai according to cnngo.com — was sold for $30 million. In Chongqing, meanwhile, China’s self-proclaimed ‘king of motorcycle manufacturing’, Zuo Zongshen, built a château-style building which has a garden with black swans and a staff of 60, according to The New York Times.

One of the country’s most lavish communal properties (a last gasp of the communist label, I suppose) is the Pangu 7 Star Hotel and residence. Residents take a private elevator up to their apartment, which is a Beijing courtyard house, and the courtyard is flanked with a swimming pool, but no one as dreary as a Chinese designer was involved: it had to be a Westerner for added chicness, in this case Italian-Brazilian Ricardo Bello Dias.

Chinese classical tones are blended with European opulence here. Marble shipped from Italy is laced with Chinese motifs. Metis, the Italian lighting consultants and the team behind Bulgari hotels, provided input as well. Baker furniture, famous from the White House and allowing no expense to be spared, fills the spacious drawing rooms and dining rooms. Lastly, to solidify Pangu’s rivalry with the Forbidden City, which was always the most luxurious place to live, special permission was granted to allow the designers to reproduce the finest of Tang, Ming and Qing dynasty artefacts, so that from the rosewood panels in the ceiling to the Imperial yellow dragon carpets nothing fails to please the eye.

From the balcony you can see the Olympic Bird’s Nest (designed by persona not entirely grata Ai Weiwei), and further away the thousands of hutongs with families living on top of each other in shared accommodation — accommodation which will no doubt one day be pulled down and given away for further redevelopment. Life here is harsh and uncertain, but while we lament the destruction of the hutongs, the Chinese government sees it as a development and improvement in Chinese lives.

As the rich get richer and the middle classes strive to improve themselves, the prices of property continue to increase. Properties sell out so quickly now that it’s about having a personal relationship with the developer, so that when the project is announced you can get there first to pay for 100 per cent of the property. Quite often this is financed by people themselves without bank lending, and the property itself may not even be built for another four years.

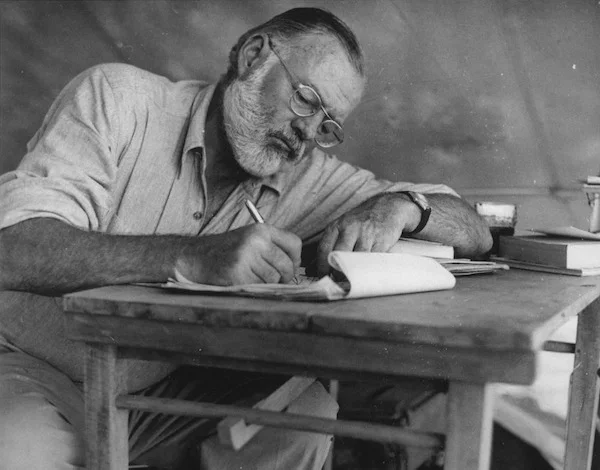

Illustration by Femke de Jong

How can foreigners compete? In short, only very liquid and wealthy foreigners can buy apartments, but even then there are a number of restrictions in place to prevent living space going to foreigners instead of mainland residents. Some of the measures that are in place to stop the billionaires buying up the whole market, for example, prevent foreign developers profiting from the buying and selling of Chinese property. In 2007, 30 per cent of investors in the Chinese property market were foreigners; in 2008 that was 12 per cent, and in 2009 it was down to 2 per cent.

For those who only wish to get away from the heaving cities once in a while, there is the option of fractional ownership of luxury properties within China. (Much of Asian tourism is in fact intra-Asian.) Banyan Tree Private Collection has a villa in Lijiang, nestling in the mountains of Yunnan, arguably China’s most beautiful province. With its canals and cobbled streets winding up and down and dotted with wooded shops, Lijiang is a living memory of distant past where travellers would stop on their route of pilgrimage to Tibet, further up the plateau to the west.

Chinese property has been dramatically redefined for the elite, but from your penthouse window (metaphorically, and sometimes literally) you can see the majority of China’s 1.4 billion people who can’t afford permanent residences, let alone luxury ones. That is a stark social divide and a harsh reality. Will it ever come crashing down?