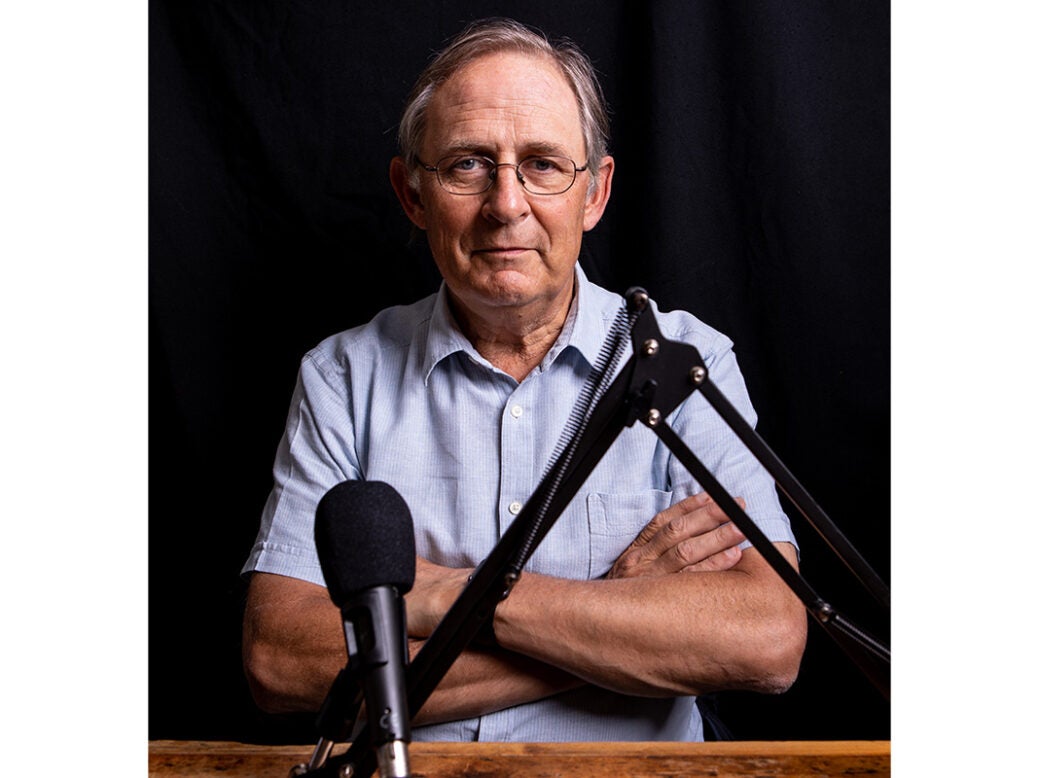

Listening to Sir Nicholas Mostyn’s new podcast, Law & Disorder, one could be forgiven for thinking he was still a sitting High Court judge.

In the show, Mostyn – who retired last year after more than four decades in the legal world – speaks with warmth and wit as he breaks down some of the biggest legal challenges facing the country today. Recent episodes have focused on the government’s Rwanda bill and the UK’s migration rules – and Mostyn’s career means he is close to the subject matter. Had he still been on the bench in the Administrative Court, he tells Spear’s he could have been grappling these problems in court. ‘In fact, I have ended up being a commentator on it.’

[See also: Spear’s Family Law Survey 2024: Leading lawyers reveal the trends shaping the industry]

Mostyn tells me about his newfound passion as a podcaster when we meet at his old chambers, 1 Hare Court, on a rainy Tuesday afternoon. He began recording after falling in love with the format through making Movers & Shakers, a podcast about living with Parkinson’s, which he hosts with Jeremy Paxman and Rory Cellan-Jones, among others. Mostyn is a natural on the airwaves – airing his forthright views is not such a departure from his career on the bench.

Biggest opponent

In the Family Division of the High Court, where Mostyn spent about half his time as a judge, he capped off his career with a ‘raft’ of judgments calling out the ‘culture of secrecy’ that had crept into financial proceedings – something that impedes public understanding of the judicial process, he says. ‘I felt that we were descending into what one judge called “alphabet soup”,’ he says, referring to the way in which family court judgments routinely use a combination of capital letters rather than real names in order to anonymise the parties. I just think it’s so completely wrong,’ he says with a sense of exasperation. ‘It is an absolute sacred cow, having these cases heard in public. People have to be named, [and cases] have to be in public so that the public can see that judges are trying cases properly.’

[See also: How increased transparency in the courts is changing family law]

His stance today may surprise some of the lawyers whose cases he has decided. Mostyn has shifted his position on the issue in recent years, having previously called financial remedy proceedings a ‘quintessentially private business’. He tells me he went back to original case law from 1913 and a House of Lords decision that he says underscored the principle of open justice in family law.

‘People have to be named because it keeps people straight. That was said by the president of the Family Division into the Gorell Commission on Divorce and Matrimonial Causes in 1912. I think the problem has been that we have subconsciously transferred the rule about privacy for children into the money cases. That’s where the error has arisen,’ Mostyn adds. ‘I have changed my mind. But then I always used to say as a judge that the judge I disagreed with most often was Mr Justice Mostyn.’

Eye for numbers

The former QC has always enjoyed a robust exchange of arguments. It was his time in the debating society at Ampleforth College that led him to turn away from his science A-levels and follow a different path. During a law degree at Bristol University, Mostyn was influenced by his professor, Nigel Lowe, who encouraged him to apply for a pupillage at 1 Mitre Court (which later became 1 Hare Court). He was called to the bar in 1980 and became pupil to Sir Peter Singer, who himself later became a High Court judge.

[See also: Best family law barristers 2024]

Mostyn credits his ability with numbers and close eye for technical detail for the progression of his career as a barrister. ‘I became popular very quickly. People liked the fact that I was able to understand the numbers.’ At Ampleforth he had been encouraged to hone his coding skills, which later helped him to build the first-ever electronic Duxbury programme (a Duxbury calculation works out an appropriate lump sum for a financially dependent party in the place of periodical payments).

‘In those days, the wife’s award was calibrated to need,’ he says. ‘You need to understand investment theory, concepts of return, and the Duxbury programme is a great algorithmic attempt to do that over the span of the subject’s life.’

[See also: The ‘Queen Bees’ of family law: long may they reign?]

In 1992, along with Peter Singer, Mostyn published At a Glance, a landmark textbook for family lawyers to assist in such financial remedy provisions.

Sir James Mumby, a fellow retired judge from the High Court, has called the guide ‘a decisive break with the past [which was] remarkably innovative in function, content, presentation and, not least, format’. It is now in its 33rd edition, while his software IP is still used ‘almost universally around the legal profession’, Mostyn says. ‘I‘ve been lucky to be able to do that.’

Setting a precedent

Away from the legal theory, Mostyn’s cases as a barrister led to new precedents that established the importance of equality in the distribution of assets after a marriage breakdown.

His involvement in the landmark White v White (2000) case, although he represented the losing husband, preceded a flurry of big-money cases in which the then QC represented A-listers and the wives of well-known British businessmen. This included securing £29 million for advertising executive Martin Sorrell’s ex-wife in 2005 and £7.5 million for the wife of local newspaper business owner Harry Lambert in Lambert v. Lambert (2002). (As a result of these successes, at a time when Mostyn was said to be charging £500 an hour for his services, the press nicknamed him ‘Mr Payout’.) Meanwhile, his final hurrah before becoming a judge, Radmacher v Granatino (2010), had a major impact on how courts interpret and uphold prenups in the UK.

[See also: Why prenups are finally becoming more popular in the UK]

‘I was lucky to be in the biggest cases. I was lucky to be in White v White,’ he says. ‘I was trying to hold the orthodox line, but it changed everything.’

It was, however, the £5 million reward that Mostyn secured for the wife in Miller v Miller (2006) that he calls a ‘career highlight’. Melissa Miller was married to asset manager Alan Miller for just under three years – and during the course of the marriage he made millions. It was determined that the wife should receive half of the money made during that time.

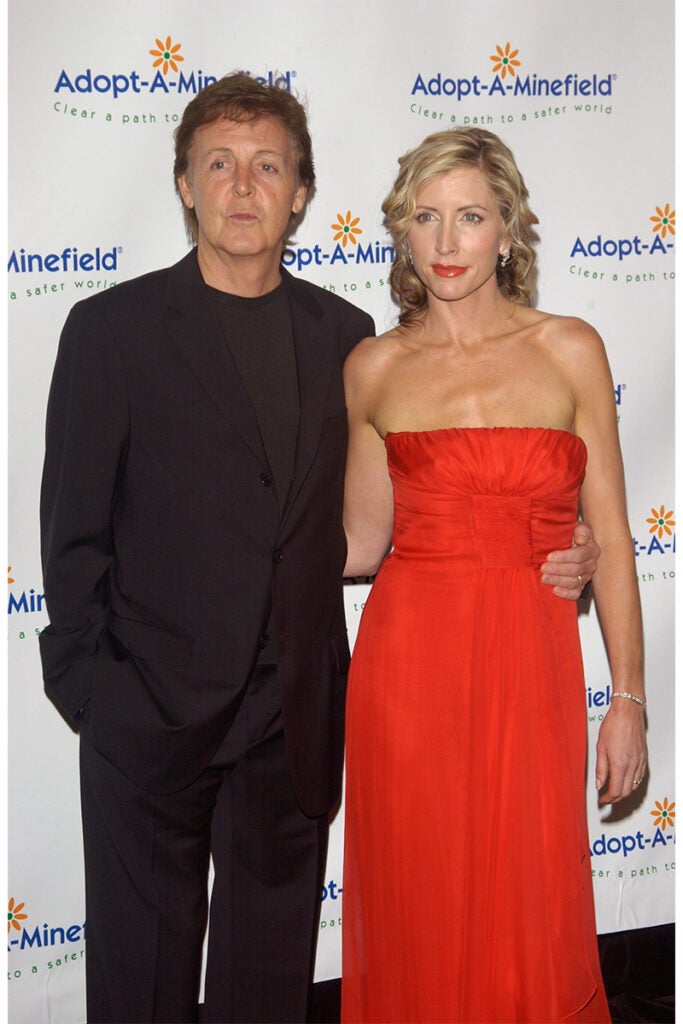

‘The main principle is now sharing equally what’s been made during the marriage,’ says Mostyn. Along with Fiona Shackleton, Mostyn represented Paul McCartney in his divorce from Heather Mills. Though the case produced a sizeable amount of tabloid fodder (Mills, who had appealed for £125 million, threw a glass of water over Shackleton’s head after she was awarded a mere £24.3 million), the case also had surreal moments behind the scenes.

[See also: Landmark divorce ruling puts the ‘sharing principle’ in the spotlight]

‘There were some hilarious moments where I put my foot in it,’ Mostyn laughs. ‘[McCartney] said, “This is the guitar”, as he showed me around his house, “on which I composed Yesterday.” I said, “I thought that was Lennon.”’ Stunned silence followed.

Game-changing decisions

Given his involvement at the forefront of cases that established equality in divorce law, Mostyn believes he has made the process ‘more efficient, more numeric, and more fair’. ‘I have been at the forefront of eradicating discrimination,’ he says. ‘As soon as the idea of equality came out, the judges all started finding reasons to depart from it. And I stamped on that as much as I could.’ This intuition, he says, led to ‘proper equality, with proper intellectually disciplined numbers’ underpinning it.

As a judge, meanwhile, Mostyn says he took it upon himself to issue ‘what I believed were game-changing decisions about certain subjects which have stood the test of time’, including on spousal maintenance, injunctions and the ‘principles of sharing’. These included FF v KF (2017), where Mostyn gave guidance on the importance of judges’ discretion in settlements where marriages are short, and SS v NS (Spousal Maintenance) (2014), where he considered how maintenance orders should be put together.

Describing his method when making judgments, Ayesha Vardag (the victorious solicitor in Radmacher v Granatino) told Spear’s that Mostyn ‘will go through all the historic law and then absolutely make his pitch for how it should be now’.

‘He’s done it again and again, as if he’s been on this huge mission to get us as close as one can within the common law system to codify the law, and bring clarity to it,’ Vardag adds. ‘It’s been absolutely marvellous – he’s been so oriented towards justice and the right thing being done.’

This feature was first published in Spear’s Magazine Issue 92. Click here to subscribe