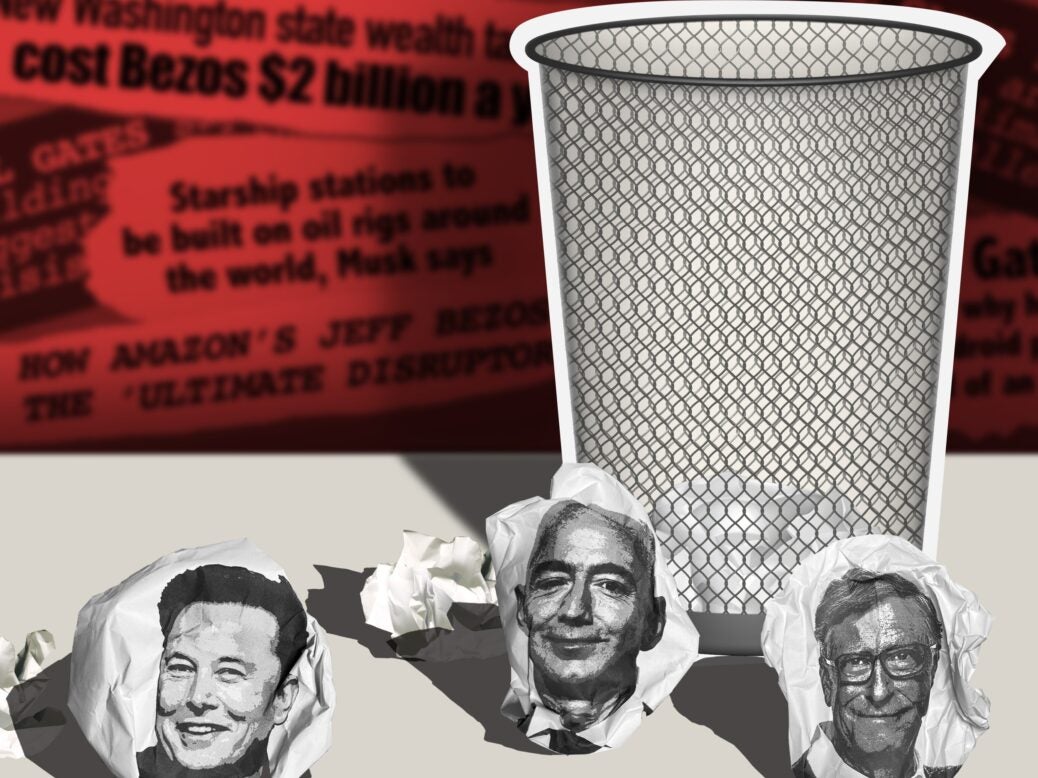

Calls to consign billionaires to the dustbin of history are getting louder. Should they be heeded?

The word ‘billion’ is commonplace. We all encounter it regularly – in news stories on everything from tech unicorns to government spending. But many people are still shocked when they realise what it means.

In 2018, Humphrey Yang went viral when he made a TikTok video that put the number – and the wealth of billionaires – into context. Using one grain of uncooked rice to represent 100,000 dollars, he gathered a small pile of 10 grains to represent a million dollars. It was less than a forkful.

Next, he showed what a billion dollars – 10,000 grains – looked like. It was perhaps three servings – certainly more than any one person would eat in a sitting. In a second video, Yang used the same scale to illustrate the then $122 billion net worth of Jeff Bezos. It took 58lbs of rice; a truly colossal quantity, especially when you consider that the net worth of the median American family is $97,300, less than a single grain.

For many, this kind of inequality feels unacceptable.

How, one might ask, can it be right for a developed Western society to allow some people to have so much while others struggle to afford basic things like food or healthcare?

And a sense that something radical should be done has begun to take root. More than three-quarters of comments about billionaires on social media now carry negative sentiment, according to analysis by Crimson Hexagon, a consumer insight firm (as recently as 2015, the balance of negative and positive comments was roughly 50:50).

Meanwhile, media outlets from Vice to the Washington Post publish pieces that speak in a matter-of-fact way about ‘hate’ for rich people and billionaires in general.

In the United States, an annual tax targeting billionaires was a central pillar of the presidential bids of Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders (supporters of the latter can buy a bumper sticker that reads: ‘Billionaires Should Not Exist’). Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the 31-year-old Democrat tipped by many to be a future candidate for president, believes that ‘every billionaire is a policy failure’.

In the UK, a group of academics, researchers, lawyers and policy wonks have banded together to form a self-styled ‘Wealth Tax Commission’. The group’s efforts to map out a what a wealth tax would look like and how it would work have received widespread media attention.

The idea has been supported by MPs, and even received a sympathetic hearing from the Conservative chair of the Commons Treasury Committee, Mel Stride. Indeed, certain polling indicates public support for such policies in the UK.

When asked which kind of tax rise they’d prefer if the government raised taxes to fund public service, 41 per cent of Britons questioned by Ipsos Mori said their first choice would be for the introduction of a new wealth tax. In the same poll, three-quarters of respondents expressed some degree of support for that type of tax.

But would measures to trim billionaire and multi-millionaire wealth really change society in the ways proponents believe? There are several different proposals on the table.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s adviser Dan Riffle, who first coined the ‘every billionaire is a policy failure’ line, tells me via Twitter that he would like to see a cap on the amount of wealth it was possible to accrue.

He suggests $40 million as a sensible figure, because ‘it’s enough to do anything anyone should reasonably hope to do in life’ and because it is 100 times $400,000; the mean net worth of an American household.

But, for Riffle, the amount is not as important as the fact there would be ‘some upper bound’ that would ‘prevent abusive and counterproductive runaway accumulation’. Not everyone on Riffle’s side of the debate advocates a cap, however.

‘A progressive wealth tax with high tax rates for billionaires (such as 5 per cent or even 10 per cent each year) is the needed tool to softly ‘ban’ billionaires,’ Emmanuel Saez, co-author of The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make Them Pay, tells me by email.

This would not amount to an outright ban, says Saez, who is a professor of economics at Berkeley, because entrepreneurs with ‘exploding wealth’ such as Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk would likely be able to increase their wealth more quickly than it was eroded by the tax. But, he adds: ‘billionaires would face headwinds and would not be able to stay billionaires for as long.’

Billionaires would be forced to sell-off of stock in order the pay the tax, which would ‘reduce the stakes that Bezos and Musk own so that they would cede control sooner (or eventually work as hired CEOs instead of owners)’. But how would it work in practice?

Arun Advani, a University of Warwick academic and member of the Wealth Tax Commission, suggests that a one-off wealth tax might be considered in the UK, to boost to the public purse in the wake of the pandemic.

One model mooted by the group would see a one-off tithe of 5 per cent on wealth above a threshold of £500,000 for individuals and £1 million for couples (once debts such as a mortgage had been taken into account).

Such a tax could lead to Sir James Dyson, Britain’s richest person, paying more than £800 million. Advani and his team project that, in total, the tax would raise £260 billion after administration costs.

***

Usually, the first argument against wealth taxes relates to efficacy; rich people will simply move elsewhere to avoid paying. Anticipating this, however, Advani and his colleagues have proposed a model that would see anyone who had been present in the UK for four or more of the last seven years obliged to pay the tax. (Someone who had been present for just four of the last seven years would pay less tax than someone who had been present for five, and so on.)

But imagine the following, says James Quarmby, a partner at law firm Stephenson Harwood: It is a sunny spring day. You are out for a walk and spot a beautiful flower on the other side of a lawn. You walk across the lawn to smell the flower and continue on your walk. Then, seven years later, you receive a demand for £10,000 – because it has been decided anyone who walked across the lawn in the previous seven years must pay a tax.

That might seem unfair; if you had known that your behaviour would have such a cost, you may have acted differently.

‘I have serious doubts as to whether [the proposals are] actually lawful,’ says Quarmby. ‘That looks dangerously like retrospective taxation, and that’s not allowed. That’s unconstitutional. Do we want to turn into a banana republic where we can just confiscate stuff from people because we don’t like them? Everyone would lose all respect for the UK and no one would invest anymore. Unfortunately, the country would suffer.’

France has had a wealth tax since 1989, although its scope has been significantly reduced by Emmanuel Macron. ‘There are very few wealthy families in France,’ says Quarmby. ‘The L’Oréal family stayed behind and a couple of others. Everyone else has gone to Switzerland, Belgium.’

He notes that under Socialist president François Hollande, youth unemployment in France reached 25 per cent. While the European Union has made efforts to ‘harmonise’ its tax system, tax competition between nations continues to exist – and continues to afford wealthy people the opportunity to avoid tax regimes where they feel they do not get a good deal.

That’s no bad thing, according to Dr Madsen Pirie, president of the Adam Smith Institute. ‘Some people want world government,’ and a world tax system, says Pirie. ‘But I’m in favour of variety.

John Stuart Mill thought that Europe prospered because of its variety, because of its many different governments.’ If one government made your life uncomfortable (in Mill’s day most likely because of your religion) notes Pirie, you had the ability to move somewhere more to your liking.

The US – which could theoretically offer billionaires the choice of paying a wealth tax or renouncing their citizenship – might be best equipped to enforce one. But surely this is at odds with the American Dream.

The majority of Americans (82 per cent) – and even of Democrat voters (73 per cent) – believe it should be possible to become a billionaire, according to a 2019 survey by the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank. After all, the existence of billionaires does not make other people poorer; the economy is not a zero-sum game.

However, says Pirie, there are three types of billionaires: kleptocrats, those who have inherited wealth, and entrepreneurs. Those in the final group (and those in the second who invest in a laudable way) can be regarded as a net-positive influence. Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, to take two examples, have generated wealth by creating things that have improved people’s lives.

What’s more, they fund important projects that range from supporting high-quality journalism (Bezos has invested heavily in the Washington Post) to laying the foundations for interplanetary travel (Bezos and Musk both have space exploration companies). Philanthropy is an important part of this conversation too. Governments spend ‘according to political pressures,’ notes Pirie.

This leads to budgets being stretched to cover competing concerns. ‘I don’t think that achieves as much as the tightly targeted wish of a single person,’ says Pirie. ‘The electorate probably wouldn’t fund the elimination of malaria, like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is.’

And while the proportion of billionaires’ wealth donated to philanthropic causes could be significantly higher, there are signs – such as Jeff Bezos’s recently announced $10 billion climate change fund, Bill Gates’ ‘Giving Pledge’ and a spate of donations in the response to the pandemic – that more good can come from wealth that is freely given by those who earned it.

An approach that acknowledges the real-world implications of a wealth tax while emphasising the importance of genuine philanthropy might be the most sensible and sustainable.

Especially if the alternative is rhetoric that vilifies people simply because they are wealthy and proposes sudden and radical tax changes that could destabilise whole economies.

Then again, perhaps this is itself an unrealistic idea, in a world that is characterised by polarisation and culture wars more than ever before.

More from Spear’s

Life of a scion: what’s it like to inherit a business empire?

What does Brexit mean for The City?