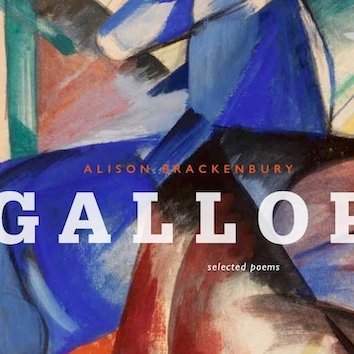

Christopher Jackson welcomes a Selected Poems by the Lincolnshire poet, and argues it will be for the anthologies

‘Happiness writes white’. This remark by French novelist Henry de Montherlant is now quoted so often, and usually with such approval, that its wisdom has begun to petrify. One wants to disturb the fossil, and see what life has been secretly active on its underside.

It’s true that, from the novelist’s perspective, endless contentment would lack drama. For the poet, things are different. The 66-year-old poet Alison Brackenbury exhibits the sense that when not writing her taut poems, she has found fulfilment in things – in other people, her business life, and in nature. All her work is supported by the sense that she is in control: in the realm of the poem by technical skill, but beyond the poem too, as a useful and generous citizen.

Here is poetry lit by the poet’s own goodness and strength. It’s a valid and not a simplistic optimism. She has genuinely totted up what is good in life, without turning a blind eye to what is troubling and difficult. It’s only that we know throughout this wise book that if a poem has been born of a vexation or a painful realisation that it has in some sense already been solved at the poem’s beginning: all things here revert back to serenity, to a commitment to generosity, and to hope.

This book comprises the best of Brackenbury’s work across nine collections: it contains one long poem ‘Dream of Power’ – a poetic rescue of the life of Arabella Stuart – but the vast majority of the book contains shorter poems packed with intelligence and rigor, full of glinting revelation. Those who have come to her through these crisp poems will be surprised to discover that she wrote a poem of such sustained length as ‘Dream of Power’.

But brevity has been right for her: it has meant that her work is satisfyingly glancing. Besides ‘Dream of Power’, an alternative route into the collection is a poem called ‘Robert Brackenbury’ about a long-dead relative. This shows the Brackenbury virtues: a sense of locality which is also a recognition of family; crisp and ordered verse with cunning rhymes; and a profound empathy for what might have provoked or influenced others.

Therefore I claim

you from dark folds of Lincolnshire

who shared my name

and died two hundred years ago

you, man, remembered there

for doing good.

This, then, isn’t the Robert Brackenbury who is meant to have enabled the murder of the Princes in the Tower in the reign of Richard III, as a googling briefly makes you think it might be. Instead it’s some other namesake, who refuses so far to surface in any search engine.

(It’s interesting to observe that Brackenbury’s career straddles the invention of the Internet. Brackenbury is in a pre-computer rhythm of life, whose poems are percolating in the computer age. It’s possible to receive an email from her, but written with the attention and care of a letter-writer.)

The poet wonders why her kind relative left no papers behind:

…did you trust

that when all shelves, all studies fell to ash

your kindness still might haunt our wilderness…

Brackenbury is wondering how someone of her kindred could leave behind no record when she is busy compiling such a comprehensive one. But unlike so many poets, she understands the extent to which non-poets refuse to live by words as poets do, and even admires the strength and restraint which might inhere in this decision. It’s this which, paradoxically, has enabled her to move people who aren’t usually interested in poetry.

For the most part, these are poems enacted in the countryside. A Londoner can open any page at random and discover a poet who knows nature intimately: they are the gentlest – and therefore most devastating – rebukes to the urban life. Gathered in these sacred pages are all the things which are missing in Victoria station at rush hour.

In ‘Grooming’, a horse’s ‘dark skin is too tender to be brushed’. Consider the years of experience required to write something so lovely and so straightforward. Or in ‘6.25’ we glimpse with fleeting truth the ‘flash of the badger’s cheek, wet from tunnelling’. In a glorious poem ‘Lapwings’, we receive this insight about the bird’s life: ‘I watched it buckle from vast air/to lure hawks from its chicks’. In that same poem, we find ‘a hare flowed/bounded the furrows’. Brackenbury’s dense lines frequently track the sequence of noticing. In that last line, the hare is quick, and so seems to flow before the eye can pick up the more specific action of bounding. Note also how there is no ‘and’ and no comma between ‘flowed’ and ‘bounded’ which conveys, as only a great poet can do, the thing we are asked to see.

Brackenbury not only observes the countryside, she also knows why things are happening around her. The detail on display recalls the Stratford boy who had seen so clearly the wind rippling along the cow’s flanks that he could remember it years later and put it in Anthony and Cleopatra.

But these are also the poems of someone well-travelled – indeed, of a high-net-worth individual, with all the knowledge you’d expect of the tourist beat. In ‘Out of Hanoi’, we visit Vietnam (‘a huge rat bobbed along the parapet’), and attend a Chinese wedding in the poem of that name. Perhaps the most sophisticated sense of place is found in ‘Produce of Cyprus’ where Brackenbury, tasting some grapes, ‘thinks of the island that grew them’. What ensues is, to begin with, a sort of Proustian journey to the land where Aphrodite is meant to have been born:

….Venus’ ground

(the rain is in sheets on my window, wet, green, blind)

there, the dry song of the cicada, there the warm nights

with the window propped open, sea’s stripe on the counterpane.

But the poem ultimately goes further, and gives the reader a reciprocal sense of place from the Cypriot perspective. It twists to imagine how we must seem to that other country: we must be enviable, but in a different way, part of a ‘prosperous country; on its window, the wealth of rain’. At this point, two stanzas in, it’s already a marvellous poem. But in the final stanza Brackenbury consumes the last grape. And then we get this:

The last is tough. The bag, as I put by the rest

rustles and whispers, Paradise is the place

of which we know nothing, which we know best.

These last lines – full of majesty and control – might be the book’s mantra. But it’s worth noting that the satisfaction of the ending is tied up beautifully by the linking rhyme. Particularly, with the word Paradise lodged in there, it is as if Dante’s terza rima has risen unexpectedly – but with a gorgeous justice – out of a poem which had seemed to have a wholly separate organising principle.

One should also be careful not to underestimate the sheer range of the poet’s optimism. In Brackenbury-land, one never feels that the dead are beyond our calling them back. One of my favourite poems in the book ‘All’ is worth quoting in full:

And all who died, from winter’s sleet

From flu, from guns, from cells grown wrong,

Still stand, one breath from fingers’ reach,

Just out of touch, all colour gone.

The dead grow smaller. From a train,

Mist takes the fields, drinks green to grey,

The fog has swept across their face.

In yard or park, they walk away,

Then wait in rooms, without a fire,

With tea uncleared, without a fuss;

In cushioned chairs, now closer drawn,

Nod to each other, not to us.

But in mid age it is not strange

To glimpse them, in the windy street,

Quiet at the kerb, who are all dead,

From guns, cruel cells, or winter’s heat.

Poetry like this deserves to float free from its maker. It needs to be carved in rock.

A final point. Brackenbury is also a poet with a superb sense of light. In almost all these poems, light is invoked, probed, and seen. It comes up from the snow (‘Five winter days were lit by the slow thaw’, Dream of Power); it emanates from human faces (‘Worn: all separate: we shine’, Monday); it is a marker of memory ‘(Why did I wake/at three in the morning/wholly convinced it was dawn?’, Crew to Manchester: December); and it spreads over the world with an indiscriminate generosity. I love, for instance, the conclusion to ‘Woken’:

Some time in the night

There was a hand which found my face,

Careless as you, as light.

Light is a presence even in the dark. In one of the many poems here which touch on horses, ‘Homecoming’, the relative ignorance of the animals as they move through the countryside – ‘They only crave heaped hay again’ – is juxtaposed with what is actually there: ‘the sudden lane/the silver poplar shivering in light’.

Most of all, light allows us to look at the world with startling immediacy. In a wonderfully tender poem ‘Your Signature is Required’, Brackenbury regretfully signs off on her parents’ will, and observes her parents’ handwriting: ‘Who will write like that again?’. Afterwards, Brackenbury sees nature with a greater acuteness than usual:

So I know that they are safe,

So, forgetting them, I pass

A C of moon so tender

She must not be glimpsed through glass.

That repetition of ‘So’ conveys with perfect weight that sense of reluctance we have when returning after such a heavy task to our ordinary lives. The commas which flank ‘forgetting them’ create another pause, before we lurch towards the poem’s conclusion.

Every poem here exhibits similar feats of technique, which are also secrets for the reader to discover. As always, this technical mastery is in the background, never obtruding on the meaning of the poem. And what is that meaning? To confront the world with love and pleasure, to interact with one another kindly, and – to use the title of one of her collections – to sing in the dark.

Christopher Jackson is deputy editor of Spear’s