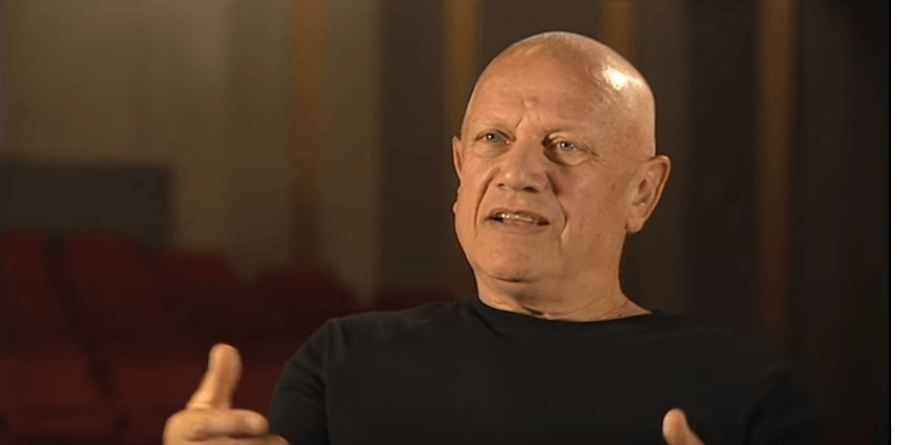

Actor, playwright and photographer Steven Berkoff shares his encounters with poverty, theatre and Faustian pacts

I live in London , and whenever I go anywhere special I take my camera with me. Fortunately, photography isn’t my main source of income so I can pick and choose. I went to Dublin recently for a few months and couldn’t be bothered to take it.

My Hollywood photographs are about celebrating the dignity of these normal people. There’s no question that Hollywood doesn’t want to know about them. My work reflects the underbelly of society; they’re the overbelly.

I find it revealing, the kind of detritus they leave behind. They used to make movies about misfits: films like The Grapes of Wrath, for example. I don’t think they want to look at the beggars now – but there are wonderful stories, and wonderful movies to be made.

Think of Charlie Chaplin: he captured poverty like no one else.

Street life

I remember photographing these old men. I used to go down to Venice Beach and talk to them about the Oscars. I’d ask: ‘How are you doing?’ And they’d say: ‘I need some breakfast, man, some hash browns.’ Then I’d ask: ‘Are you going to the Oscars tonight?’ And remember, these are the most down and out people.

They’d say: ‘Oh, it’s not really my thing. I don’t think it’s really up my street.’ It’s terribly moving. There’s no question these people deserve to be recorded. One guy I met is a pianist called Pino.

He kept his piano in a garage, and used to bring it out to the beach on casters. He’d say: ‘Please leave something if you like the music, and if you don’t, that’s OK too.’ And he played like a genius: he was just phenomenal.

You just watch him and think: ‘How come this man is sleeping out on the beach?’ He would improvise classical music. I’ve never heard piano playing like that – not in the best concert halls in the world. He was better than Barenboim.

Finding energy

I have written about these people. But in my plays, people are articulate, energetic and self-defined. In plays like East (1975), I depict poor working class kids. These children have their peculiar energy, characteristic of the deprived working class youth. T

heatre comes from the street – curious corners of society. Michael Jackson’s moonwalk came from Paris and was picked up by street kids.

They’re inventing because there’s no alternative. You don’t have lots of toys and dodgems, cars and junk stuff: these kids are phenomenal artists. Another man I met was in mining. He said when Obama came to power, business went down and they laid everyone off. He just came down to LA, and then his eyesight went.

I got him on video: beggars and down-and-outs have kind faces. There’s none of this greed you see in middle-class bourgeois careerists. And they all have books – they’ve got to do something just to hold on to sanity.

Theatre has become too comfortable. It started just after the war, when grants were suddenly made available to theatres. At that time theatres were run by actors: the drama they made was astonishing, devastating, frightening – powerful. They were actor-managers; that status developed them as responsible beings.

When the academics came in, they thought they’d like to become directors of the theatre, though they had no knowledge. When the Arts Council started giving funds, they didn’t trust the actors.

People like Trevor Nunn or Peter Hall came in. The actors lost responsibility; they became drunkards, rioters, and escaped to the movies.

Harvey’s ghost

I did my play about Harvey Weinstein, Harvey, recently. I did a try-out for eight days, but it was badly reviewed. I didn’t want them to review it as it was a work in progress. It’s a great play: I wrote it, it took me six months to learn it; and now I won’t do it again.

Weinstein’s a fat, disgusting pig, but underneath that he’s a very confused man in pain, and he’s lost everything. He made a Faustian pact: now he’s lost his wife, his kids and he’s in a clinic, with Kevin Spacey for company.

I made a light-hearted comment in the press once: I said the Old Vic had become a bit simple since Kevin Spacey took over. He wrote me a long letter to say how beastly and horrible I was to criticise his theatre.

He’s a very talented actor, though. On the street, all you have is a community and camaraderie with your fellow aliens. That’s when you become inventive and articulate. Higher up the strata, people become less articulate in terms of the body.

Maybe they can analyse the iambic pentameter, but otherwise there’s a death mask on them. Pino’s cat died and it absolutely broke his heart.

He’s an obsessive genius but no one can speak to him because they’re in awe of him. I want to get back to Hollywood and see him before he dies.

As told to Christopher Jackson

This first appeared in issue 68 of Spear’s magazine, available on newsstands now. Click here to buy and subscribe.

Read more:

Diary: ‘Paralysis is the word for our current political predicament’ – Rowan Williams

Diary: Alexander McCall Smith on finding joy through travelling

The Diary: Sophia Money-Coutts on California